#Islam

Using Philosophy in Da’wah

Published

By

Dawud Omar

Bi-smi llāhi r-raḥmāni r-raḥīm

In recent years, there has been some attention on the question of using philosophy in daʿwah. Considering my experiences in both philosophy and daʿwah, I thought I’d weigh in on the subject. First, the terms philosophy and daʿwah are quite broad and would require a series of discussions to elucidate. Hence, for the purposes of this article, I am going to focus on the particular daʿwah strategy of appealing to philosophical arguments to prove the existence of God (i.e. philosophical proofs). I will argue that we should not appeal to such philosophical proofs since it may be problematic. My reasons are as follows: first, such philosophical proofs do not work since they can all be undermined by philosophical skepticism. Second, they help create the rational framework which legitimizes the rejection of God. Third, such philosophical proofs can be spiritually misleading. My goal in this paper is to raise contentions against the current trends in hopes that Muslims develop better strategies for engaging with people of other faiths, more particularly those who are skeptical of God’s existence.

Before I continue, it is important to make a few disclaimers. First, this paper is not meant to argue that philosophical proofs should not be used or even that they are religiously prohibited. I do not have the scholarly qualifications to make or even endorse such an injunction. However, from a philosophical standpoint, I can perhaps share some personal reflections as to why it could be problematic to use such philosophical proofs. Second, this may be offensive to some people. I understand the implications of this paper, if true, could appear to undermine entire disciplines. However, this doesn’t necessarily have to be the case. Even if I do not accept the ability of such philosophical proofs to prove the existence of God, that does not mean that such arguments do not have any utility. Third, this work is not meant to be an exhaustive treatment of the topic. To do the topic justice would require much more time and energy than I can afford to give at the moment. Lastly, my main objective isn’t to convince anyone of my opinion since it is still a work in progress. My hope is to raise some serious concerns and have philosophers, regardless of their views on the matter, engage with the subject at hand.

The Problem of Skepticism

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

PC: Prottoy Hassan (unsplash)

To begin, let’s consider an imaginary theistic skeptic named Socrates. Socrates does not believe in God simply because he does not believe there to be enough evidence. Socrates doesn’t necessarily commit himself to the claim that no God exists or even that knowledge of God is impossible. Rather he has never been presented with any convincing evidence to believe in any God. Nevertheless, Socrates doesn’t disparage believers or ridicule them for their beliefs. If anything, part of Socrates envies believers for their impassioned faith and sometimes wishes he could believe in God. The only problem is that, if he were to do so he would just be living a lie, pretending to believe in God. The fact is he has no good reason to believe in God. If we were to engage with Socrates we may be inclined to present him with a philosophical proof. Several philosophical arguments can be used. For example, there are cosmological arguments, teleological arguments, and ontological arguments. Each series of arguments appeals to different facts to deduce the existence of God. All arguments appeal to logic. Let’s suppose Socrates engages with some of the arguments. Let’s suppose he finds them interesting and can even appreciate how there is a diversity of philosophical proofs. Nevertheless, in the end, he is still unconvinced.

One reason he may not be convinced by some of the arguments is that they may commit certain logical fallacies. For example, some arguments use facts about our universe to infer the existence of God. However, when similar reasoning is used to infer that God is evil or uninterested in human affairs, then it is not accepted.1This objection was pointed out by Hume in Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. Another example can be found in Spinoza’s Ethics, where he goes from proving the existence of God to deducing his conception of pantheism. Such a conception can be problematic as it directly opposes the traditional monotheistic view of God found in the Abrahamic faiths Another more fundamental reason Socrates is unconvinced is that all of the philosophical proofs appeal to logic. Logic can be defined as the rules for correct reasoning. But what justifies these rules other than the rules themselves? Each philosophical proof already assumes the validity of certain rules before using those same rules to prove the existence of God. But what reason do we have to believe we as a species can reason correctly or even reason toward truth? We could suppose that we can reason correctly or even reason towards truth because we have been created that way. But then that would just be begging the question.2 Begging the question (also referred to as circular reasoning) is a well-known logical fallacy. For more on logical fallacies, refer to The Top 10 Logical Fallacies: https://muslimmatters.org/2022/06/14/10-muslim-logical-fallacies/

This problem is not unique as many philosophers have already identified this as one of the problems of skepticism. One well-known philosopher who sought to tackle the problem of skepticism was the 17th-century French philosopher Rene Descartes. In his Meditations, Descartes’ subject attempts to develop a strong methodology by which a person can come to know things with absolute certainty. To do so he engages in a process of radical doubt to try and arrive at something that is indubitable. For the moment, everything is called into question; all of his prior beliefs, his senses, the existence of God, and even his own existence. In the end, he concludes that the only thing that cannot be doubted is the fact that he is doubting. Hence, he realizes, “I am, I exist, must be true whenever I assert it or think it.”3 Descartes, R., “Meditations II” in Meditations on First Philosophy. The moment you try to question your existence, only further proves that you exist. This notion is most famously referred to as the Cogito (for cogito ergo sum, which translates to “I think, therefore I am”).

Although Descartes believed he solved the problem of skepticism, many philosophers disagreed. If anything, Descartes may have opened a can of worms that has become difficult to contain. One major contention with the Cogito is that it begs the question. To say ‘I think’ already contains within it the notion of ‘I am’ and therefore, it becomes fallacious to try and use the former to conclude the latter. Furthermore, to say I think, therefore I exist, is to assume that whatever thinks exists. If we are unable to establish anything with absolute certainty––including our own existence––, then what leads us to believe whatever thinks, must necessarily exist? However, to be fair, there is another way of interpreting the Cogito which is philosophically stronger and more consistent with the Meditations.

One can also interpret the Cogito as a “thought-act” by which as long as we are acting upon it, intuitively demonstrates our existence.4 Wilson, M. D. (1978). Descartes. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, Descartes. The validity of the proposition itself wouldn’t be contingent on our thinking more so than it would be on our experience of thinking. We may question the notion of thinking, but we cannot question the fact that the mere notion of thinking seems a certain way to us. We cannot deny our own subjective experience regarding any possible illusion since the mere fact of denying them only further substantiates them. However, this too is based on a few problematic assumptions. It assumes we can know anything about our own conscious experience–or the transparency of our thoughts. It also assumes we can know anything about how our experience relates to existence–or that our thoughts correspond to reality.

According to Socrates, based on the arguments for philosophical skepticism, you wouldn’t be able to definitively prove the existence of God. One could respond to this by arguing that based on his line of reasoning, we wouldn’t have reason to believe in anything. For example, how can you know you are not dreaming right now? How can you know you are not a brain in a vat? How can you know you didn’t just come into existence five minutes ago, with someone implanting you with a collection of false memories? The fact of the matter is that if you were to take this level of skepticism seriously, you wouldn’t be able to live your life. For Socrates, this would actually be a fair point, and it may be a point that he would be willing to concede to.

Socrates would agree that we can’t really know anything with absolute certainty and is fine with acknowledging that fact. After all, that’s what it means to be human. We are epistemically limited. We believe certain things at a certain point in time and then change our beliefs once we come to realize they were wrong. No one would ever argue that he or she possessed only true beliefs, for we are all epistemically fallible. However, for Socrates, believing in the existence of God is to believe you have access to absolute truth. It is more than just a claim to knowledge, it’s a claim to power. The difference between belief in God and belief in the external world, for example, is that he is being asked to accept the former with absolute certainty, whereas he would happily accept the latter based on probability. Regarding the former, he is being asked to believe in something––anything––with absolute certainty. Something which will consequently affect everything he knows and in most cases, require him to reorient his life according to that belief. Unless you are willing to argue that it is merely probable that God exists, he has no reason to confidently commit himself to that belief.

To be fair, some apologists who appeal to philosophical proofs do make it a point to mention that their arguments are based on premises that are, at best, most probable. However, at the same time, many theists would also claim that belief in God must be established on the basis of certainty. In other words, it is not sufficient to simply believe God could exist or that His existence is very likely. Thus, if we assume all philosophical proofs seek to prove something true; and we assume all philosophical arguments which seek to prove anything true fail under skepticism; then philosophical proofs fail to prove the existence of God.

You may feel inclined to disagree with Socrates but that would only support his point. Assuming Socrates is wrong and that there are philosophical proofs that do prove the existence of God, the fact that he is unconvinced by them demonstrates his fallibility. This raises an interesting question: is our faith in God contingent on our intellectual abilities to discern the fallacies in our reasoning? If so, this is what has led many skeptics to ask why would God punish a person for not believing in Him, when He has not provided that person with sufficient evidence and the intellectual ability to discern the evidence. Sure, the evidence may be sufficient for you, but the point is that it is not sufficient for others. For others, like Socrates, there is just no rational justification for believing in God.

The Age of Reason

PC: Giammarco Boscaro (unsplash)

Before addressing Socrates, it’s worth exploring some of the socio-political factors that have shaped the way we currently think. We can start with what is sometimes referred to as the Age of Reason (i.e. the Enlightenment). This was a period in Europe that was marked by great intellectual activity and scientific advancement. It was during the Enlightenment that we began to see a shift in philosophy, from focusing on questions of metaphysics to focusing on questions of epistemology. This established incredible new ways of approaching and interacting with the natural world. However, many philosophers later would go on to criticize the Enlightenment as being the main catalyst for many of the problems that we are still facing. Regardless of one’s views on the Enlightenment, no one can deny its enormous influence in shaping the way we think today. My main contention with the Enlightenment, for the purpose of this article, is that it created the secular rational framework which we must all operate under.

One of the ways the Enlightenment created this rational framework was through the elevation of reason, as a means of knowing. The elevation of reason is what essentially defines the Enlightenment. This has been notoriously attested in Kant’s “What is Enlightenment?”, where he writes, “Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity.” Immaturity, he goes on to explain, “is the inability to use one’s understanding without guidance from another. This immaturity is self-imposed when its cause lies not in lack of understanding, but in lack of resolve and courage to use it without guidance from another. Sapere Aude! [dare to know] ‘Have courage to use your own understanding!’ — that is the motto of enlightenment.”5 Kant, I., “What is Enlightenment?” Hence, the Enlightenment represents a shift where people can begin to think and draw conclusions for oneself, independent of any external authority. Man becomes his own guide and reason becomes the primary source of acquiring knowledge.

The push to elevate reason as the main epistemological source may seem entirely sensible, especially when you consider it from the vantage point of thinkers from that era. However, historically, that was not always the case. People used to interact with the world through various other means, many of which were equally valid and in some cases superior. For example, people used to understand the world through myths and poetry. Others relied more on faith, spirituality, intuition, personal experience, or even revelation. One could argue that the transition from mythos to logos goes as far back as the Ancient Greek philosophers. Plato’s allegory highlights reason as the main catalyst which takes a person out of the cave of ignorance and into the light of absolute truth. Even if we trace the primacy of reason to the ancient period, I would certainly say that it was cemented during the Enlightenment.

An extension of the elevation of reason becomes the deification of man through the Cartesian subject. This can be seen in the project of Descartes, where all knowledge and certainty is fundamentally dependent on the self. The subjective object becomes transformed into an objective subject. The Cartesian subject is objective because he is a neutral observer who is disinterested, dispassionate, and detached from any biases or social and cultural contexts. The Cartesian subject is also disembedded and detached from any tradition. The departure away from tradition is one of the hallmarks of the Enlightenment. Man becomes wholly independent to the extent that he becomes self-sufficient and is thus, able to arrive at knowledge all by himself. Finally, man becomes disembodied. He becomes the subject that is separate from all other objects to the extent that he is able to manipulate objects and recreate them. In the end, reason becomes the tool that is used to legitimize man’s subjectivity and impose it on the rest of the world.

Reason sets the terms of the discussion as it prioritizes a secular view of the world. That becomes the starting point and is justified through the notion of neutrality and impartiality. The basic problem with the secular starting point is that it already assumes the skeptic’s worldview. The burden of proof is now shifted to the theist to have to prove his God and the only proof that will ever be accepted is that which passes the test of reason. Hence, the theist is always in the attack, while the skeptic merely has to sit back and remain in defense. But as the saying goes, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”6 Taken from Audre Lorde. Reason is the main secular tool that is used to reject faith. It creates and sustains the structures which allow the rejection of God to exist. But why should theists have to play pretend and assume the skeptic’s worldview? Why not start with a worldview that already assumes God? One could argue that God is the fundamental axiom, without which there can be no further conversation. One could argue that everything rests on God, and God is the starting point of everything.

Considering the secular terms set by reason, appealing to philosophical proofs also leads to the rational justification of disbelieving in God. In other words, by appealing to such arguments you are not only validating a skeptic’s rejection of God, but you are also actively justifying it. The reason is that you are implicitly agreeing with the epistemic framework of the skeptic by attempting to operate within those restraints. To illustrate this, imagine a person (A) who relies on debates to determine what is true. Debates, when done well, can be a good way of exploring some of the strongest arguments of both sides. However, just because one position triumphs over another in a debate doesn’t mean it’s the most accurate position. Suppose person (A) invites you to debate the existence of God. For only if you can defend your position successfully in a debate, will it prove your position. My argument is that one should not appeal to such a debate as a way of establishing the truth. Regardless of whether you win or lose the debate, by simply engaging in it, you have already lost. Appealing to such a limited epistemological framework not only yields falsehood, but it actively legitimizes it.7Wittgenstein raises a similar contention against G.E. Moore in his response to skepticism. According to Wittgenstein, G.E. Moore failed to understand the specific context (the language game) in which he was trying to establish what he knows. “For when Moore says “I know that that’s…” I want to reply “you don’t know anything!” – and yet I would not say that to anyone who was speaking without philosophical intention. That is, I feel (rightly?) that these two mean to say something different.” Interestingly, by attempting to respond to the problem of skepticism, G.E. Moore validates the problem. Wittgenstein writes, “If Moore is attacking those who say that one cannot really know such a thing, he can’t do it by assuring them that he knows this and that. For one need not believe him. If his opponents had asserted that one could not believe this and that, then he could have replied: “I believe it”. Moore’s mistake lies in this – countering the assertion that one cannot know that, by saying “I do know it”.” Wittgenstein, On Certainty.

One could argue that reason is only harmful when used incorrectly. For if we were to reason correctly, simply by conforming to the rules of correct reasoning, then there would be no harm since the rules themselves will never result in error. However, this is part of the problem, a problem which I would refer to as the fallacy of reason. We have been led to believe that, through formal reasoning, a person will always be able to arrive at the truth. However, in an attempt to gain mathematical precision, formal reasoning has to isolate itself from its context and simplify its content. Thus, formal reasoning becomes limited as it can only be applied to highly simplified domains of knowledge. To exclusively depend on such reasoning to arrive at truth is to reduce all human experience to that which can be quantitatively measured and assessed through a limited formal system. Our human experience is too complex and ambiguous to be measured and contained within a limited system. Additionally, our formal systems are defined by us. We set the boundaries and define the terms which fundamentally depend on specific ways we understand and compartmentalize our universe.8 Some theists who may subscribe to a type of logical realism may not agree with this, in which case I would ask them to consider the following question: does God create something to be logical because it is logical or is it logical because God creates it to be logical?

Adhering to such a formal system is also misleading as it gives its practitioners the subtle impression that they are wiser than they are. The logical ability to assess the validity of any argument, identify logical fallacies, solve abstract puzzles, and so on, empowers one to think that they have knowledge, or are in a better position to acquire knowledge. This ignores the timeless lesson taught by Socrates that wisdom is in knowing that our knowledge is worth nothing.9 Plato, Apology. Nevertheless, a person with no knowledge or experience of the world now becomes empowered with the tools of rationality since all they have to do is sit in their armchair and assess the logic of an argument. Thus, formal reasoning inadvertently suspends any genuine philosophical reflection. It’s no accident that we now find ourselves in a period where a “philosopher” with absolutely no experience in the field can feel confident debating an expert or writing articles on religious matters. Philosophy, a practice that began in wonder and was nourished by a passion to examine the world, gets reduced to an instrument that is merely played by the most ignorant entertainers.

Another notable problem with reason is that it is used to legitimize physical and ideological subjugation. If reason is the absolute infallible source of knowledge, then why has it led us to some of the worst calamities in human history? The Age of Reason, a period where human beings became more enlightened, where reason was supposed to be our guide to the straight path, was followed by the two World Wars in which millions of people suffered. Reason became the means of manipulating and recreating objects in our world, which was then used to completely obliterate the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Additionally, philosophy became the apparatus used to justify colonialism and imperialism. The language of reason became the main weapon of the oppressors which allowed them to legitimize their oppression under the guise of rationality and civility. This can be illustrated in the moral philosophies that have been established purely on the basis of reason. Those who have been most affected by oppression are those who have been most excluded from the conversation since they are unable to engage in ethical discourse using the language of reason. Thus, the primacy of reason dominates our understanding of normativity and dictates which forms of resistance are considered legitimate (rational discourse) and which forms are not (violence).

In the end, my argument is not that we should completely disregard reason. Or that reason should not be used to try and understand the world or arrive at truths. My argument here is simple: appealing to philosophical proofs is problematic because it validates the rejection of God. First, all philosophical proofs validate the current rational framework. They do so by simply participating and operating within it. This is similar to how a debater has to agree with the terms of a debate, including its results, before being able to take part in that debate. The current rational framework can lead to the belief in God. But it can also lead to disbelief in God. This is due to the limitations of reason. Based on my argument, if a person is led to believe, through the current rational framework, that there is no reason to believe in God, such a belief is validated.

Qur’ānic Epistemology

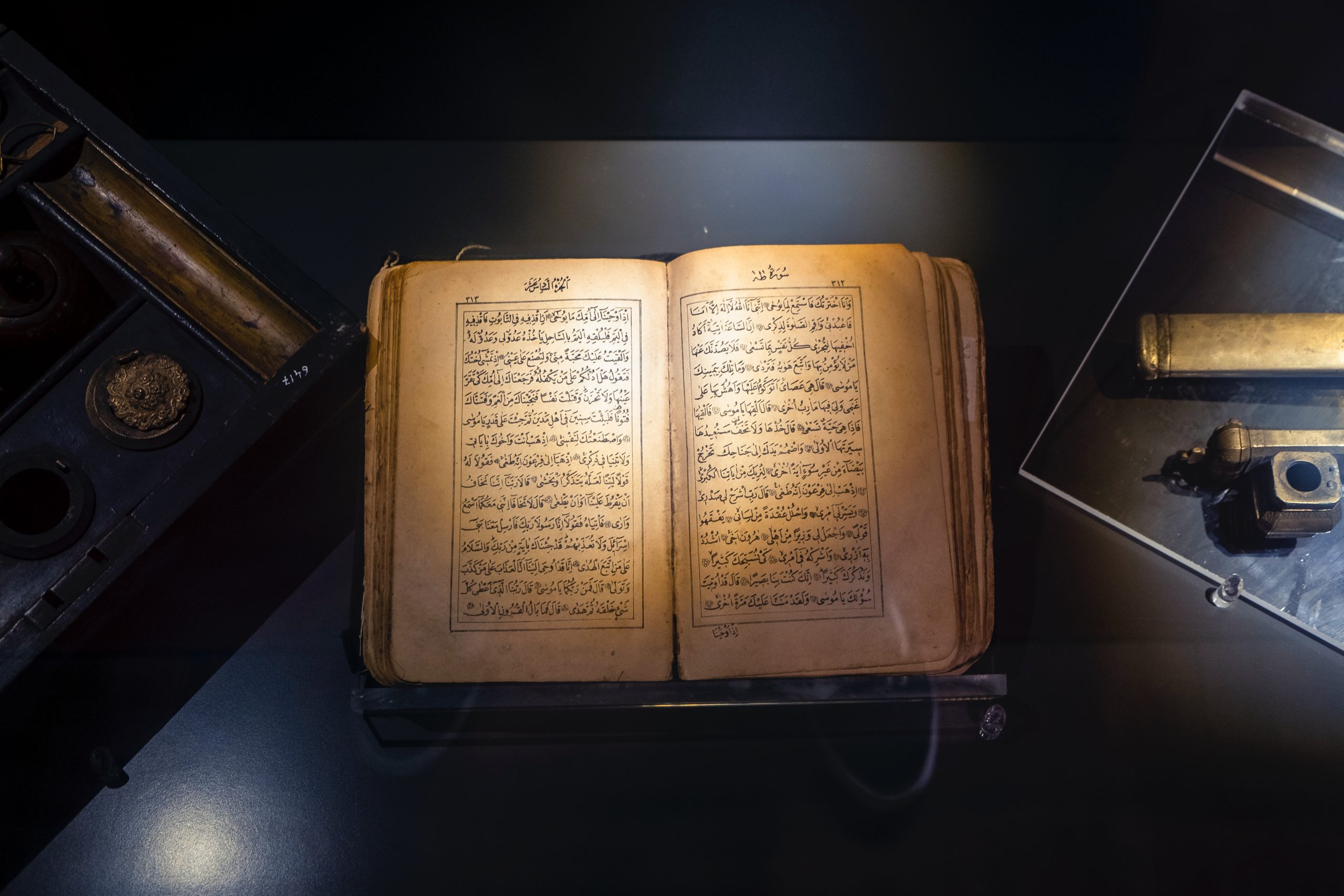

PC: Omer Haktan Bulut (unsplash)

Another more fundamental problem with appealing to philosophical proofs is that they can be spiritually misleading. First, such philosophical proofs invite us to rationally assess the nature and wisdom of God. Second, such philosophical proofs falsely assume the primacy of reason over faith. Third, such philosophical proofs give the false impression that belief in God is a result of one’s intellect. Of course, this is all based on a particular understanding of religion. For example, if one subscribes to a particular religious tradition that happens to favor reason over faith, then my argument would be unsound. My argument here is that all of the aforementioned reasons hinge on the Qur’ānic worldview.

Appealing to a purely rational framework proves to be misleading as it invites skeptics to logically assess God. Skeptics are now in a position to interrogate the greater wisdom behind things like the problem of free will and the eternity of hellfire. Any response which does not pass the test of human reason can be justifiably discarded and dismissed. Reason transforms a person from once acknowledging we can never truly fathom God’s wisdom to now questioning God’s wisdom, and then, ultimately rejecting God. But what if such questions are beyond our ability to comprehend? What if there are just some things that we will never be able to understand in our current state? This does not mean we should not strive to seek an explanation but perhaps we should just accept the fact that we may never get all the answers, at least until we are in the presence of God.10“˹Remember˺ when your Lord said to the angels, ‘I am going to place a successive ˹human˺ authority on earth.’ They asked ˹Allah˺, ‘Will You place in it someone who will spread corruption there and shed blood while we glorify Your praises and proclaim Your holiness?’ Allah responded, ‘I know what you do not know.’” Qur’ān 2:30. Any rational attempt at solving these philosophical problems is simply our flawed attempt to rationalize God’s infinite wisdom. Perhaps it is not our objective in life to solve philosophical problems or figure out the mysteries of our universe. Perhaps our main objective in life is to be virtuous. Starting first and foremost with the exclusive worship of God.11 “And I did not create the jinn and mankind except to worship Me.” Qur’ān 51:56

Somehow we have been philosophically misled into thinking that reason ranks superior to faith. But what justification do we have to support that notion? One could argue that faith is the true foundation of all knowledge. In fact, without faith in anything, we are left with philosophical skepticism. What reason do we have to believe we as a species can reason correctly or even reason toward truth? Thus, we must have faith in something to have knowledge of anything. The question is what will you choose to have faith in? Faith in God leads to certainty. Faith in God justifies reason, not the other way around. Yet, we have been grossly misled into thinking that reason should justify faith. Perhaps it’s because according to Descartes, “two topics – namely God and soul – are prime examples of subjects where demonstrative proofs ought to be given with the aid of philosophy rather than theology.”12 Descartes, R., “Dedicatory letter to the Sorbonne,” Meditations on First Philosophy. However, according to the Qur’ān, only God can guide us to the truth. “Allāh is the Guardian of the believers—He brings them out of darkness and into light.”13 Qur’ān 2:257.14 It’s also worth noting how Al-Ghazālī overcomes the problem of skepticism compared to Descartes. In his Deliverance from Error, Al-Ghazālī states, “At length God Most High cured me of that sickness. My soul regained its health and equilibrium and once again I accepted the self-evident data of reason and relied on them with safety and certainty. But that was not achieved by constructing a proof or putting together an argument. On the contrary, it was the effect of a light which God Most High cast into my breast. And that light is the key to most knowledge. Therefore, whoever thinks that the unveiling of truth depends on precisely formulated proofs has indeed [narrowed] the broad mercy of God.”

Consider the following narration by Aisha

Ultimately, this is how we have misled theistic skeptics like Socrates. Due to the philosophical climate, Socrates mistakenly assumes that belief in God must be based on intellectual conviction and so he reasonably searches for intellectual proof. But what if belief in God is not based on reason, but rather a more holistic process? Perhaps we can say belief in God is not a result of one’s intellect, but rather one’s spiritual condition. I believe this is more consistent with the Qur’ān. For God says, “Do they not reflect upon the Qur’ān, or are there locks upon [their] hearts?”16 Qur’ān 47:24 The Qur’ān certainly appeals to the mind, but it also appeals to the heart. It penetrates the heart, soul, and mind, in a way that no other scripture does, and it invites all of humanity to sincerely reflect. To say that belief in God rests on one’s ability to be convinced by intellectual arguments is to give them too much power and privilege those who are intelligent over those who are not. To say that belief in God rests on one’s spiritual condition is to privilege those who are most sincere over those who are not. This explains how you can have the most sophisticated intellectuals disbelieve in God, and the most uneducated Bedouins believe with absolute conviction.

The Qur’ān makes it clear that people have the freedom to reject God. If a person wants to find reasons to disbelieve, they will and if a person sincerely seeks to come closer to God, they will. There are many instances in the Qur’ān, where people were presented with miracles and yet still disbelieved. For example, we are told about the story of Prophet Ṣāliḥ

What is most interesting in these stories is how people received what many skeptics are requesting today, empirical evidence––it doesn’t get more demonstrative than a miracle––and yet they still disbelieved. Perhaps we can say, the reason is that according to the Qur’ān, belief in God has less to do with intellectual conviction and rational proofs and more to do with the psycho-spiritual condition of the heart. Consider where God says that even with the Qur’ān itself, which is understood to be the best of all miracles, “They will not believe in it. That was what happened with the peoples of long ago, and even if We opened a gateway into Heaven for them and they rose through it, higher and higher, they would still say. ‘Our eyes are hallucinating. We are bewitched.’”19 Qur’ān 15:13-15. This presents us with an interesting lesson about the nature of belief in God. This suggests that for those who refuse to believe in God, no amount of evidence will ever be enough since there will always be reasons to doubt.

A truly sincere person does not require any philosophical proof to believe in God. Consider the fact that the Qur’ān is the best articulation for the existence of God. “This is the Book about which there is no doubt, a guidance for those who are God-conscious.”20 Qur’ān 2:2. It is the greatest expression of demonstrative proof. Yet it does not appeal to any complex philosophical proofs. Thus, we can conclude that philosophical proofs are not the best arguments to use to prove the existence of God. Focusing exclusively on such rationalistic approaches impedes us from exploring and developing our own epistemology. Instead of imposing our rational framework––which is largely guided by the Western Enlightenment project––onto the Qur’ān, we should let the Qur’ān guide our understanding and broaden our epistemological framework. We should remember that Islam has its own unique philosophical framework which differs greatly from the West in that Western philosophy is fundamentally built on doubt, whereas Islamic philosophy is fundamentally built on certainty.21This acute observation was made by Seyyed Hossein Nasr in “The Meaning and Role of ‘Philosophy’ in Islam.” Studia Islamica, no. 37 (1973): 57–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/1595467

Conclusion

In the end, this is not to say that philosophy or reason are inherently bad or that we should refrain from engaging in philosophy. This is also not to say that we should not appeal to reason or care to engage with each other rationally. This is also not to say that philosophical proofs are useless and thus not worth exploring. Although I do not believe in such proofs, that does not mean there is no utility in them. Such proofs may still be useful as they can aid and develop our understanding of philosophy. Such proofs may also be beneficial to those who already believe in God since they may reassure them and support them in their belief. However, in regards to using such proofs to convince skeptics of God, I do not believe they work and may even become counter-productive. According to the Qur’ān, belief is a holistic process. It certainly involves the mind, but also, and especially, involves the heart. It is a manifestation of ethics that results from one’s spiritual condition. Disbelief in God is not an intellectual problem, but a psycho-spiritual one. It requires a spiritual solution. By appealing to a rational framework we reduce the extraordinary message of the Qur’ān and shift focus away from any real philosophical engagement with it.

And Allāh

[ I would like to thank all of those who read earlier drafts of this paper and provided feedback including, Edward Moad, Nazir Khan, Hatem Al-Haj, Joshua Rasmussen, Abdul-Malik Merchant, as well as others. That said, all opinions and views expressed here are my own. Anything good from this is from Allāh

Related:

– Religion: Not A Substitute For Science – MuslimMatters.org

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Dawud teaches various courses in Philosophy at Howard University and Marymount University, as well as other colleges. He received his B.A. in Philosophy, with a minor in Linguistics, and his M.A. in Philosophy from George Mason University. He also received another M.A. in Political Science from American University in Washington D.C. and is currently pursuing his Ph.D. in Philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania. His primary areas of research interest include moral and political philosophy. He also has a deep interest in Islamic studies and has spent some time studying overseas.

Faith, Identity, And Resistance Among Black Muslim Students

Moonshot [Part 12] – November Evans

From The Prophets To Karbala: The Timeless Lessons Of Ashura For Muslims Today

Moonshot [Part 11] – The Fig Factory

Nationalism And Its Kurdish Discontents [Part II of II]: Kurds And Turkiye After Ottoman Rule

Moonshot [Part 11] – The Fig Factory

Moonshot [Part 12] – November Evans

Moonshot [Part 10] – The Marco Polo

Moonshot [Part 9] – A Religion For Real Life

Genocidal Israel Escalates With Assault On Iran

[Dhul Hijjah Series] Calling Upon the Divine: The Art of Du’a (Part 1)

IOK Ramadan 2025: Four Steps | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Do Your Best | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Giving Preference to Others | Sh Zaid Khan

Sithara Batcha

May 3, 2023 at 11:06 AM

Awesome article, Jazak Allahu Khayran!

I think similar approaches could also be used within the fold of Islam itself.

One recurring example: a sister is not wearing hijab. Well meaning brothers pepper her with arguments from the Quran and Sunnah. Rather than being convinced, she comes up with all sorts of counter arguments (implicit versus explicit commands, grading of hadiths, legitimacy of ijma, etc). The brothers now with their competitive spirit up, hammer her with more rulings and logical arguments (various shayks fatawa, nature/biology of men and women, etc). The sister responds with her counter arguments. Both sides forget adab and the whole thing degenerates.

Yet, if the brothers realized that the main issue was not logic, but a need for further spiritual development, things may have gone differently.

Aquaman

May 5, 2023 at 9:38 AM

The reason for so many genders is to make people with mental illnesses, personality disorders, or who are mediocre feel better about themselves and feel special, without having to actually do anything to merit such.

There is a good reason that selfish, delusional and narcissistic behaviour and having a gender identity go hand in hand. Look up cluster B personality disorders.

Gender as it is used today just means imaginations and feelings. People who have nothing of any merit can use this as a way to stand out and demand preferential treatment. It is nonsense. It is like the fat is beautiful movement – it is apologism for negative personality traits or illnesses, a way of pretending that these bad things are good. Very often these are people with no life, no jobs, no prospects, no relationships. They are utterly toxic a nd delusional.

Every deviation and perversion is justified and applauded. Mental cases and delusional psychotics are not crazy, they are brave and we must applaud them.

All of this is nothing more than a society spiritually bankrupt and morally hollow. People worship themselves, their desires and feelings are their God. And that is what these people are doing. They are worshipping their mediocrity and, worse, expecting others to do the same.

sinawi

May 19, 2023 at 1:29 PM

“Another more fundamental reason Socrates is unconvinced is that all of the philosophical proofs appeal to logic. Logic can be defined as the rules for correct reasoning. But what justifies these rules other than the rules themselves? Each philosophical proof already assumes the validity of certain rules before using those same rules to prove the existence of God. But what reason do we have to believe we as a species can reason correctly or even reason toward truth?”

this allegedly more ‘fundamental’ reason is not only unmotivated (as all radical skepticism is) and confused, but it’s also self-defeating. re the last point, what skeptic Socrates fails to realize is that the basic rules of logic are self-evident – and his very doubt about the arguments for God’s existence show this. For he argues in something like the following way:

1. If I don’t have “reason to believe we as a species can reason correctly or even reason toward truth”, then I don’t/won’t believe p (where p = God exists)

2. I don’t have reason to believe we as a species can reason correctly or even reason toward truth

3. therefore, I don’t/won’t believe p

the argument in 1-3 instantiates a form (i.e., modus ponens) to whose validity skeptic Socrates himself is committed (even if he fails to recognize it).