#Culture

A Hassan’s Tale Story: No Strings On Me

A major firefight broke out to the north, and we hunkered in a sandbagged kitchen as roaches scurried over our legs and sweat poured down our faces. The walls were cracked and patched with mold. The ham was thawing, and I could smell it.

Published

See the Story Index for Wael Abdelgawad’s other stories.

The National Lottery

I’d survived so many close calls that lately my men’s declarations of “the national lottery” had become awed, almost frightened.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

“Still burnin’ your luck,” said Daniel, my corporal, repeating one of his favorite lines. He made a twinkling motion with his fingers. “Smoke comin’ offa you like bubbles off a fish.”

At the age of fifteen I was a captain in the Kataeb Regulatory Forces, one of the right-wing Christian militias slogging our way through the blood and rubble of the Lebanese civil war. I was young to hold such a rank, but it was late in the war, and so many fighters had died that anyone with talent was being promoted. I was an extraordinary soldier, having been taught to fight and shoot from the time I could walk. My own mother, before meeting my father, had been a teenage tank driver in the Numur – the Tigers militia. A slender, blond-haired woman, she drove an M41 Walker Bulldog tank, and with nothing more than an AK-47 could put a bullet in the eye of a sniper at five hundred meters.

A jeep drove up and a soldier hopped out with a message for me to report to Boulos Haddad. Boulos was the leader of the Lebanese Christian forces, and a member of President Amin Gemayel’s cabinet, though it was said that Boulos was the power behind the throne. He was also my uncle. One might have thought I’d be coddled. In reality it was the opposite: I’d always been given impossible assignments, to the point where my men sometimes wondered if command had a reason for wanting me dead.

I’d begun to suspect that this was indeed the case. My father had been a dissident, an author and poet who spoke vehemently against the war, before he and my mother were obliterated in a car bomb explosion. I saw it happen, and sat stunned, cut and bleeding from the ears, seeing the tree leaves papering the street – trees always lost their leaves with car bombs – and smelling the stench of urine. I was told that the PLO killed them, and I believed it then. But I was experienced enough now to know that the PLO used C4 for car bombs. C4 smells like almonds. It was our side, the Kataeb, who used ammonium nitrate fuel oil. ANFO smells like piss.

I kept my speculations to myself.

Lost Puppet

In the square we passed the bloated corpse of a dog. It lay on its back with its legs sticking up like pins in a pincushion. A moment later we drove by a headless female body, then past two young men rotting beside a pile of sandbags, their hands tied behind their backs. In the grassy island in the center of the square, someone had erected a Christmas tree adorned with spent bullet casings.

“Begin a look a lots like Christmaaaaas” Daniel sang in terrible English.

I did not laugh. My emotional interior was blasted and wrecked, like the scene of a car bomb explosion. Neither sobs nor laughter could be manufactured. I went through my days following orders, fighting who I was told to fight, because I was too stupid to think for myself, and too unimaginative to visualize myself doing anything else. When I was little I’d seen the movie Pinocchio, and it had frightened me. Pinocchio was a lost puppet, abducted, trapped in a nightmare, surrounded by children being turned into donkeys. The only voice of sanity in his life was his ineffectual conscience, reedily protesting in the form of a cricket.

I was the lost puppet now, dancing as the puppet master pulled the strings, deaf to my own conscience, watching the world transform into a hell on earth, and not only did I not try to stop it, I was a part of it.

But I’d recently met a young woman, Lena, who taught English at the American University of Beirut. She’d awakened a spark of life and faith in me, and I began to think that maybe I could be more than a soldier. Maybe there was a life for me beyond this river of blood, if I could just survive a little longer.

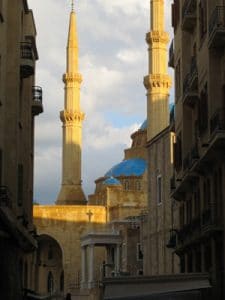

I’d also begun to learn a little about Islam, and it intrigued me. All I knew that was they worshiped only one God, Allah, and that this worship was the crux of their existences, defining everything they did. I sensed the truth in this. It was the seed of something powerful and huge, but the seed had not yet sprouted in my mind, and I could not grasp its significance.

I’d recently survived a PLO ambush in an alley. They could have finished me off, or even tortured me for information, but instead they’d given me water, and returned my Beretta 92 handgun. I couldn’t forget the way the Palestinian commander had then turned his back on me, standing in line with his men to commence the Muslim prayer. When I’d asked him how he could be so confident that I would not shoot him in the back, he’d only said, “Allah is watching my back.”

Where did such faith come from? It was as if Allah was not only the man’s God, but a trusted friend. Not a concept, a fairy tale, a line from a catechism, or a bearded old man drawn from the pages of a dusty book. No, their God was a living, present Being who watched your back when you prayed in the alley. This fascinated me. I knew that the Palestinians were only here in Lebanon because they had been driven from their homeland. They’d suffered decades of massacres at the hands of the Israelis, along with the loss of their land and homes, and were subjected to untold daily brutalities. Was it that experience of suffering and hardship that engendered such faith? Or was it something about the religion of Islam itself, some inherent spring of truth that nourished the soul?

I didn’t know for sure that I wanted to become Muslim, and in any case I knew that converting to Islam was not possible as long as I remained part of the Kataeb, or indeed as long as I remained in East Beirut. But there was no escaping the war. I was trapped in the same downward spiral of death that my entire nation was locked into. How could I possibly break free?

How We Achieve Peace

Boulos’s fortified house sat on a hilltop overlooking the waterfront. The guards moved a barricade to admit us. As soon as I stepped out of the Jeep, Rocket dashed to me. She was Boulos’s dog, a Saluki Persian Greyhound – an expensive purebred – with long legs and a barrel chest. I’d had few friends after my parents’ deaths: my little brother (who had since disappeared); the house manager, who we all called Tant Gala, also now disappeared and presumed dead; Daniel and another soldier named Saber, who’d been among Boulos’s house guards back then; and Rocket. More than anyone, it had been Rocket who’d brought me back to life. My heart swelled with love as I kneeled and scratched her ears, and rubbed under her chin.

Daniel waited outside as I entered with the maid, who showed me to Boulos’s study. His personal bodyguard Mr. Black stood outside the door, as usual, as unmoving as stone. He was a mute man with a long purple scar across the front of his throat. No one knew his real name.

Black indicated that I should raise my arms. I’d left my rifle in the Jeep, but I carried a Walther PPK handgun, ankle revolver, two knives, and a loop of paracord, all of which Black confiscated. He then accompanied me into the study.

Boulos, a portly man in camos and a brimmed army hat, reclined with his feet on his desk, smoking a cigar. He grinned. “The prodigal nephew appears!” His voice was gravelly and grating on the ears. “Merry Christmas.”

“Yes sir.” If the Kataeb had indeed killed my parents, and if command was deliberately trying to get me killed, then this was probably the man behind it all. I should hate him. But all I felt was a burning desire to know the truth. None of which I let show on my face.

“What?” He waved his cigar. “No enthusiasm for Christmas? Don’t you like peace on earth? You know how we achieve peace?”

“No sir.”

The grin disappeared as he took his feet off the desk and sat upright. He reached beneath his desk and brought out a long-barrelled Colt revolver that, I knew, had been passed down from his grandfather. He licked the barrel and tapped it on tobacco-stained teeth. “We bury our enemies. Every last one of them, men and women, headfirst in the dirt. There’s nothing more peaceful than a cemetery.”

My face must have registered some flicker of emotion, because he said, “You don’t like that? Too much of your father in you. Ma’lish.”

He pressed the intercom button on his desk and instructed the maid to “bring the ham”. A moment later she hurried in, a simple country girl in a sleeveless cotton dress, her long brown hair braided down her back, and both shoulders showing vaccination pockmarks. Her skinny arms were burdened with a huge plastic-wrapped frozen ham, which she stood hugging.

“On the desk, idiot!” Boulos roared.

The girl deposited the ham and practically ran from the room.

Boulos explained that he wanted me to deliver the ham to his lawyer. He handed me the lawyer’s name and address on a slip of paper. When I read it, I did a double take. It was in West Beirut.

Boulos laughed. “You need a job done right, you call Simon Haddad. And give the lawyer this too.” He pushed an envelope to the edge of the desk, and pinned me with a brutal gaze. “This is important. Don’t fail.” He handed me some spending money and told me to return personally when the job was done.

Of course I wouldn’t fail. I didn’t do failure. Pull my strings, watch me dance.

Texas Turkey

Daniel and I stashed the ham in the Jeep, and I explained the mission as we headed for the Green Line. The city was divided between East and West, with Christians on one side and Muslims on the other, separated by a sniper-infested no man’s land. There were checkpoints where commercial traffic could pass, but thousands of people had been abducted at the checkpoints, or simply shot. For men of fighting age like myself and Daniel, a checkpoint was a death roulette, with the odds against us.

No, we’d have to sneak across the Line.

“If you want to sit this one out,” I told him, “I understand.” This was quite possibly a suicide mission. There was no point in both of us getting killed.

Daniel tweaked his mustache. “Goin’ west with a prayer and a gun. Lemme see that envelope.”

“Forget it.”

“Wanna hold it to the light, me. Get a little see what, know what.”

I had to admit I was intrigued as well. I held the envelope to the sun myself as Daniel drove. “It’s a check.”

“How much?”

“I can’t tell.” I put it back in my pocket.

At the barracks we changed into civvies – for me, jeans, old sneakers and a Led Zeppelin t-shirt, and for Daniel slacks, Italian walking shoes and a dark green polo shirt. The man spent every cent of his meager salary on clothes.

“Afraid you’re going west with a prayer only,” I said. “Leave your guns in your locker.”

“Cap,” Daniel protested. “Lemme keep one gun. Crazy not to.”

I shook my head. “You can keep a non-military issue knife, like a pocket knife. We need something Islamic too, like those white caps the Muslims wear.”

We drove over to the shops on Shar’ah Al-Arabi. Small pocket knives were easy to purchase, as well as a sports backpack to carry the ham in. But we tried four different stores, and nearly got shot by a shopkeeper who thought we were Muslims, before we found a couple of Muslim-style knitted skullcaps, which we stuffed in our jeans pockets.

The sun was high and hot, and I worried about the Jeep, which had begun to cough like an old dog. We stopped at a service station with a huge hole blown in the overhead awning. A shell had struck the station last year and embedded itself in the asphalt, failing to explode. The national lottery. I filled the radiator, but we hadn’t reached the Line when the engine belched smoke, rattled and died.

We hoofed it. When I jammed the ham into the backpack it felt soft on the outside. It had begun to thaw. Daniel insisted on carrying it, and I let him. Though I was taller, he was as strong as an elephant.

“You know this ham get us killed, eh?’

“Why?”

“Muslims don’t eat pork.”

Black day, he was right! I considered. “If anyone asks, we say it’s turkey.”

Daniel looked doubtful. “It got no legs.”

“A big turkey. With the legs cut off. No, I know. It’s a Texas turkey!”

“Texas turkey ain’t got legs? How it walk then?”

“I don’t know, I just made it up. That’s the point. No one else will know either.”

Daniel nodded slowly. “Might could work.”

The Green Line

As we walked down the side of the road, other pedestrians crossed the street to avoid us. I looked like a normal Beiruti teenager, if such a thing existed, and Daniel looked downright classy. Nevertheless, something about us was betraying the fact that we were dangerous. We were safe enough here in East Beirut, but once we crossed the Line we’d have to be less conspicous.

“Walk like a civilian,” I urged.

“How a civilian walk?”

“I don’t know. Slump your shoulders like you’re depressed. And stop touching your pocket.” I’d noticed that he kept fingering the pocket he’d put his knife in. It was a tell.

We skirted sandbags, debris and garbage. There was hardly a building in Beirut that had not been damaged, and some were flattened, as if a mighty fist had hammered them to the ground. Bullet-pocked murals displayed either political satire, or uplifting scenes of an unblemished, shining Beirut. They were old, dating from early in the war, before words like hope and peace became punchlines in jokes.

The Green Line was a three-block wide death zone that ran the length of the city. Over the years plants had taken root and grown in its streets. It was literally wild, thick with ferns, trees, jasmine, bougainvillea, marijuana – a riot of green. Hence the name. Magnificent old colonial buildings lined either side, crumbling.

It was hard for me not to think of the last time I’d walked through here. I was eleven years old, dragged along to a brothel by my idiot older cousin Sarkis and his minder Maron. We were attacked by Amal militiamen, and I killed two. One I shot in the hip, and he twisted on the ground, trying to stop the bleeding as he screamed, “O Ali!” Until Maron put a bullet in his forehead. I had never killed anyone before. The memory of that day still haunted me, standing out even amid the flood of violence I’d experienced since. You never forget your first, they say.

“Cap?” Daniel stood in a shaded doorway, scanning. “Gotta move.”

I shook off the memory.

We went through buildings, back door to back door. We slipped through chinks in fences, crawled through artillery holes and windows, climbed over walls and through ditches. A major firefight broke out to the north, and we hunkered in a sandbagged kitchen as roaches scurried over our legs and sweat poured down our faces. The walls were cracked and patched with mold. The sound of rifle fire echoed in these empty urban canyons, so that you could never tell exactly where it was coming from. The ham was thawing. I could smell it, meaty and raw. I took it from Daniel, giving him a break.

The firefight died out, and we moved on.

We came to Damascus Street, a wide, deserted boulevard that formed the arterial center of the Green Line. No one inhabited these old buildings but snipers and soldiers. There was nothing but to cross it. Fortunately it was a forest, with trees towering four stories high, and dense underbrush. We surveilled it through a dirty window. The street was suddenly, eerily quiet. No snipers taking potshots, no artillery, no patrols that I could see. The hair stood up on the back of my neck. There was something wrong here.

But we were soldiers on a mission, and puppets must do as the strings tell them, so we proceeded, crawling on hands and knees into the plant growth. The ground was a mixture of soil, shattered masonry, broken glass and litter. It was full of sharp edges, and soon my knees and palms were raw. The odor of the ham was so strong I was afraid it would give us away to any nearby patrol.

Ambush!

We were nearly across when a twig snapped somewhere just to my left. Down on my hands and knees, I froze, holding up a fist to signal Daniel to stop. I listened, my whole mind dedicated to detecting the slightest sound. The snapping sound came again, along with a rustle from the other side, and light footsteps in front.

Black day, this was an ambush! It was a setup, and like fools we’d crawled right into it. I thought of Lena in that moment, and felt sad that I would never see her beautiful face again. I didn’t know what I wanted from her, or what I thought might happen between us. But she was a soft voice in a hard world, a source of kindness and strength, and I would miss her. I also regretted that I had not had the opportunity to learn more about Islam.

Shut up, I told myself in a fierce mental whisper. Mourn your own death later. For now, get up and fight! I was about to motion to Daniel to stand and draw his knife – might as well die on our feet – when something leaped onto my back. Painful needles drove through my t-shirt and into my skin. At the same moment, a dark creature ran at me and scratched my face.

What on earth? These were cats! They leaped out of the undergrowth and down from branches, dozens of felines of all colors and breeds. Snarling and yowling, they swarmed over my backpack, clawing and biting, tearing at it. There was one on my head and I grabbed it and threw it away, feeling its claws tear at my scalp.

Daniel pulled on my arm. “Come on, Cap. Ham’s KIA. Leave it to the beasties.”

I set my jaw. I’d beaten PLO fighters, Amal militiamen and even well-armed Syrian army regulars. I’d survived nearly every type of attack with every weapon short of a nuclear bomb. I was not going to be defeated by a bunch of crazy cats. Yanking my arm free from Daniel’s grip, I ran at the cats and snatched them off the meat, flinging them away as they clawed my hands and arms. I seized the ham and sprinted, throwing caution to the wind. Not even caring anymore, I marched in the open, hugging the ham.

Daniel tugged at my arm again. “Cap, there’s a checkpoint ahead. Can’t go there.”

We’d left our IDs behind, since our names were obviously Christian. The soldiers might shoot us on the spot.

“I don’t care. Put on your Muslim cap.” I was possessed by a sort of suicidal mania. This had come over me in battle at times. We went straight up to the checkpoint. They were Fateh militiamen, PLO regulars. Some had their rifles trained on us, while a gray-haired sergeant with rough cheeks regarded us stonily.

“As-salamu alaykum,” I improvised. “Making a delivery to my uncle, Nasir Aziz.” This was indeed the lawyer’s name. I’d heard it said that the best lie was built on truth. “Texas turkey, all the way from America.” I grinned broadly. “We had to sneak through Christian territory to collect it at the wharf.”

For some reason I was not afraid. I’d killed PLO soldiers, and they had killed my men, but I held no hatred for them. My experiences in the last few years had led me to think of the Muslims and Palestinians as my equals, and in some cases my betters. I’d been shown compassion by them in situations where I knew for a fact that my side would not do the same.

A tall, gaunt soldier poked the ham with the barrel of his rifle. “What is this stuff on it? And what happened to you?”

For the first time I realized that the ham was a mess. Chunks were torn out, and it was covered in cat fur, along with blood from my wounded arms.

Sheepishly, Daniel explained about the cats, telling the story of how they’d ambushed us. “But we made it. All praise due to Allah.” He began to recite the Quran flawlessly. I’d not known he could do that.

The soldiers were not listening to the Quran. At the description of the cat ambush, their faces grew incredulous. One began to laugh, and soon they were all cracking up.

“Go, brothers.” The sergeant waved us on. “Take your Texas turkey.”

Looking At You or Me

We walked on. We no longer had the backpack, so we lugged the filthy Texas turkey in our arms, passing it back and forth. I was roughly familiar with West Beirut from occasional incursions. We made our way toward the lawyer’s address, sometimes backtracking when we made a wrong turn.

“How do you know the Quran?” I asked.

“Part Turkish, me. My granny taught me the ways and hows.”

After two hours of walking we found the lawyer’s building. The elevator was out of order, so we climbed the steps wearily.

Nasir Aziz, Attorney at Law – a shiny-faced man in an Armani suit – gaped in astonishment as I dumped the dirty ham on his desk, then handed him an envelope. He opened the envelope, took out the check and nodded. “This is what I needed. As for that“ – he gestured to the ham, his face contorted in disgust – “throw it in a dumpster. Go, you both stink.”

Rage rose up inside me. I had not braved the Green Line to be treated like a hired hand. Boulos could treat me that way, and I had to accept it. But not this man. I leaned across the desk and stared into Aziz’s eyes. I did not have to try to appear intimidating. My inner killing field streamed out through my gaze, and Aziz saw it.

“Do you know who I am?” I said quietly.

He drew back. “Only – only that you work for Boulos.”

“I am Simon Haddad. We are not leaving without a thank you and some Arab hospitality.”

The lawyer blanched. Though I was young, my reputation was widespread. “Of course,” he stammered. “I’m sorry.”

Three hours later we stood outside, showered and in fresh clothes, and our bellies full of chicken and rice, hot coffee and baklava. It was about an hour after sunset. We’d been introduced to the man’s entire family, including a flirtatious and otherwise pretty teenage girl whose eyes seemed to look in two directions at the same time. Nasir also gave us a generous payment for our trouble.

Outside, Daniel grinned. “Man so scare, he ‘bout to ask you a’ marry his daughter.”

“Who, the cross-eyed one? I couldn’t tell if she was looking at you or me.”

Daniel guffawed. Watching him, thinking of the ridiculousness of the day, something strange and light came over me. I threw back my head and, for the first time in years, began to laugh.

Come to Success

A flock of geese passed overhead, calling to each other. The sky was growing dark, and we had a long trip home. At least it would be easier to cross the Line at night, under cover of darkness.

The call pulled at me. No, it lifted me out of my muddy self as a mother lifts an infant from the cradle. In East Beirut we had church bells, and they were pleasant enough, but this was different. This was a man breathing his soul into a microphone, imploring me to travel with him to a land where spirit mattered more than substance, and where God might come down from the heavens and lay a finger on a man’s chest, turning him from a walking corpse into a living, breathing human being. In that land, I imagined, I could kneel beside a river and wash the stinking death from my hands.

Simon, the caller seemed to say, you can be a real boy now. You don’t have to be a puppet anymore, serving villainous masters with hidden motivations. You can serve the One who brings light, clarity, and inner success.

I thought of Pinocchio, freed from his strings, singing, “I got no strings to hold me down, to make me fret, or make me frown. I had strings, but now I’m free. There are no strings on me.” That was early in Pinocchio’s adventures, with much hardship still ahead of him. But in a way, it was the beginning of his liberation.

Only a minute ago I had laughed for the first time in ages, and now I began to cry for the first time since I lost my parents in another life, another world. At first it was only a few tears, but there was a spiritual artery inside me that had been clogged with a mountain of shame, denial, blood and rage, and as the pressure reached critical levels the dam broke. No strings on me, I thought, and it was not a statement so much as a prayer and a wish. No strings on me. I squatted there on the sidewalk, covered my face in my hands and wept as I had never done, racked with sobs, mucus running, gasping for breath.

Daniel said nothing, but squatted beside me and put an arm around my shoulders. I was his superior officer, but he was ten years older than me, and in many ways I was still a child.

The call to prayer ended. Nearby, a pair of cats yowled and fought. In the distance, an artillery gun started up – theirs or ours, it was all the same – the sound echoing across the city. Ka-thoom, ka-thoom, ka-thoom. I leaned into Daniel and let him hold me.

THE END

Check back every other week for a new story by Wael Abdelgawad.

See the Story Index for Wael Abdelgawad’s other stories on this website.

Wael Abdelgawad’s novels – including Pieces of a Dream, The Repeaters and Zaid Karim Private Investigator – are available in ebook and print form on his author page at Amazon.com.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Wael Abdelgawad's novels can be purchased at his author page at Amazon.com: Wael is an Egyptian-American living in California. He is the founder of several Islamic websites, including, Zawaj.com, IslamicAnswers.com and IslamicSunrays.com. He teaches martial arts, and loves Islamic books, science fiction, and ice cream. Learn more about him at WaelAbdelgawad.com. For a guide to all of Wael's online stories in chronological order, check out this handy Story Index.

Faith, Identity, And Resistance Among Black Muslim Students

Moonshot [Part 12] – November Evans

From The Prophets To Karbala: The Timeless Lessons Of Ashura For Muslims Today

Moonshot [Part 11] – The Fig Factory

Nationalism And Its Kurdish Discontents [Part II of II]: Kurds And Turkiye After Ottoman Rule

Moonshot [Part 11] – The Fig Factory

Moonshot [Part 12] – November Evans

Moonshot [Part 10] – The Marco Polo

Moonshot [Part 9] – A Religion For Real Life

Genocidal Israel Escalates With Assault On Iran

[Dhul Hijjah Series] Calling Upon the Divine: The Art of Du’a (Part 1)

IOK Ramadan 2025: Four Steps | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Do Your Best | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Giving Preference to Others | Sh Zaid Khan

Sam

May 18, 2021 at 4:37 PM

Here I was thinking we’d get a short story every now and then, but this seems like the beginning of a new series!!

Wael Abdelgawad

May 18, 2021 at 5:39 PM

I wouldn’t call it a series, exactly. More like a collection of unrelated stories. Next story will be about a neanderthal girl 100,000 years ago, rejecting her people’s animal worship and trying to develop her own idea of God, while at the same time watching a band of homo sapiens that have encroached on her land.

Sam

May 18, 2021 at 7:00 PM

That sounds really cool. I was listening to a talk a while ago about how fortunate we are to have the Quran in our lives, because it tells us about Allah – who He is, where He is, how to reach Him etc. But people who feel their fitrah organically settling on monotheism, without the guidance of the Quran, can spend their lives searching for Allah without knowing how to find him. It was specific to the Hunafa, who lived in Arabia, after the time of Ibrahim (AS) and before Muhammad (SAW) – but your stories seem like they’ll take that angle too. Looking forward to the next one in particular!

Wael Abdelgawad

May 19, 2021 at 4:09 PM

Sam, is that talk online? Do you have a link?

Huda

May 20, 2021 at 2:44 AM

This is a masterpiece!

The senses, the settings, the thoughts, the actions, all bases covered in such a rich and diversely vibrant style. May ALLAH SWT bless your craft and let us be privy to more readings. (^^)

Wael Abdelgawad

May 21, 2021 at 12:18 AM

Thank you Huda, I appreciate your words.

Sam

May 21, 2021 at 7:10 PM

Wael – ‘afwan, it was part of a class I take so no public link

Shoaib

November 6, 2021 at 10:16 PM

Thank you for this excellent story. I am glad I came across it. Can’t wait to explore more of your writings.