#Current Affairs

Intergenerational Islamophobia And Shame – An Unpacking

Published

The Seeds

There are seldom few childhood favorites that I obsessively consumed in my formative years –be they books, films, TV shows- that haven’t molded my ideas and my general understanding of the world around me in a fundamental way. I have the irrepressible, and some might say maniacal, urge to inspect the back of antiquated wardrobes in search of Narnia. I adopted the cognitive dissonance of the Disney renaissance period; that the uncompromising quest for a male companion is an unquestionably radical act. Labyrinth left my basic notion of motherhood awash with complicated, gothic undertones. And I won’t go into what kind of irrational fears the inexplicable zeitgeists of Quicksand and the Bermuda Triangle imbued upon me.

These images, intonations, and impressions, color my thinking in almost imperceptible, but undeniable ways. Whole dialogues lay dormant in my brain, only to be roused and brought forth to my consciousness by a word, situation, feeling –providing the linguistic scaffolding for my internal processing.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

What interests me about the age-old debate of nature versus nurture, rebooted in the age of social media, is not the oft-explored issue within the Muslim community and beyond, of how much media and cultural influence is healthy and productive for our children. What interests me is the neglected matter of how a global cultural climate of Islamophobia has impacted us overtly and implicitly as Muslim parents and, by extension, how this dominoes on and through our children.

What interests me is the neglected matter of how a global cultural climate of Islamophobia has impacted us overtly and implicitly as Muslim parents and, by extension, how this dominoes on and through our children.Click To TweetThe Roots

As a parent, you are forced to address your own baggage and internal biases in order to parent from a secure and healthy place. And while the parenting industrial complex encourages us to do this with regards to our own emotional makeup, we very rarely take the time to interrogate how a media landscape that constantly positions the Muslim and Islam as ‘Other’, has impacted our sense of belief and practice. Nowhere is parental self-reflection and analysis more important than the impressions we have of Islam – our very sense of purpose and direction. What are we passing onto our children, knowingly and unknowingly, about a value system we ascribe to?

Empire

Looking back at my own history, as the product of a third-generation, South Asian household in Britain, bearing the indelible fingerprint of Empire, my understanding of Islam was forged by the experiences inherent in these three disparate contexts. It resulted in an enduring dichotomy that placed Islam and ‘Muslimness’ as antithetical to the ‘rational’, ‘enlightened’ thinking characteristic of Western liberal democracies. The idea of religious thought as intellectually deficient is naturally woven into the backdrop of our existence.

For many South Asian Muslims of my grandfather’s generation, who emigrated to the United Kingdom due to labor demands in the 1960s, expressions of Muslimness in the public domain were what got you in trouble in the workplace —my grandfather was forced to leave several of his blue-collar jobs due to his prayer schedule —, and what led to aggression and violence in the streets. It was bad enough to be foreign by nature, but to be actively, selectively foreign wasn’t going to endear you to anyone.

The subcontinent’s position in Empire plays a critical role in the identity of its diaspora. The Imperial construct of a spectrum of ‘otherness’ graciously held the elusive promise of greater proximity to ‘whiteness’ to its South Asian subjects. This led to many first and second-generation South Asian Muslims with the perceived option of whitewashing – being acceptable and accepted through a display of secular sensibilities. For South Asian Muslim families in 1960s Britain, Islam was a part of the identity that got ripped away from you as you re-rooted on foreign soil and according to ‘British values’. A sepia-tinted relic of their former -apparently less civilized- existence that wasn’t fit for the public-facing, professional world, and which was best practiced in the hushed privacy behind closed doors.

A Very British Islam

By the time I was born, those knee-jerk, second-hand responses to our religious heritage were pacified and ingrained into my being. My impulsive impressions of Islam were formed through this historical distillation, but the rationalization of these impressions came from further afield -from an intellectual diet that was dominated by mainstream culture, and which ossified my impression of Islam as a regressive, dark, and out-of-date ideology.

I was able to watch Disney’s Aladdin and totally avow the depiction of Muslims as savage without a hint of self-reflection or thinking. The irony being, of course, that the social anxiety around Islamic belief centres on the idea of it as culturally deficient, yet it is secular, mainstream portrayals of Muslims –and indeed other minority groups– which expose a deficit in understanding, a willfully obtuse approach to other cultures, resulting in dangerously misleading and reductive representations on page and screen.

The turbaned, foreign-tongued villain as archetype -reinforcing this Star Wars-like, Manichean duality of good and evil/secular humanism and Islam- had created a cultural grammar of danger, threat, and cave-dwelling monstrosity that was inextricably linked with Muslimness.

And while I situate the roots of my disordered feelings about Islam within a uniquely British, South Asian cultural inheritance, it is clear a cultural climate that has cultivated this has a wider impact on Muslims in Britain. It seems I’m not entirely alone in how this public/default/rational liberalism versus shameful/closeted/irrational Islam dichotomy impacts my impressions of Islam within the wider Muslim community in Britain.

The entirely beneficial and positive waves of Muslim immigration to the British Isles since my grandfather’s generation have enriched and diversified the Muslim and wider community in Britain today in ways that are too numerous to list. For the Muslim community, in particular, it has brought with it much-needed Islamic scholarship and a more bold, rich, and varied approach to Islam. It has expanded British Islamic knowledge and practice and created a community that is far greater than it has ever been, al-hamdulillah.

Modern Muslim Shame

Overwhelmingly, the tsunami and onslaught of negative media portrayals continue to have an extensive impact on British Muslims of the Millennial and Gen Z demographics across race and class. This is most obviously laid bare in the athan-alarm clock phenomena –that unique sense of embarrassment and terror that strikes in the heart of a Muslim when our Muslimness is most audibly brought to the fore in a public situation. This homogenized experience, which includes various ‘embarrassing’ wudu stories, has gained a currency online – getting caught ‘foot-in-sink’ handed so to speak. As well as numerous other common cultural anecdotes regarding the shared mortification and collective shame of being Muslim in public spaces – being discovered in prayer, finding yourself secularizing religious belief, despite our best intentions not to ‘Prayer…is kind of like meditating…’.

These very relatable stories of a uniquely Muslim wince when our Muslimness is foiled, and an attempt to attach our beliefs to seemingly more palatable symbols. It seems our most uniting feature as British Muslims is the public shame we feel from elements of Islam.

It seems our most uniting feature as British Muslims is the public shame we feel from elements of Islam.Click To TweetCorporate Distortion

Corporate media, for example, appears to be preempting an anticipated objection to visible Muslims in advertisements by almost always justifying their presence with an overt endorsement of liberal values, the rainbow flag carrying Niqabi. Popular culture and media appear to have created this Muslim Frankenstein based on ignorance and lazy assumptions, the spectre of which now haunts it in its current quest to appear woke and inclusive. These explicit and implicit references to the Muslim subject bleed through and stain our own conception of our religious identity. We have begun to feel it necessary to justify our existence, bizarrely, through skateboards and super-human acts of kindness. We appear to constantly frame our religious beliefs using secular principles of individual and civil liberty rather than religious obedience, as though they require justifying and cleansing through secular paradigms. Why are we willingly adopting the language of Quraish –in championing acts only when they are divorced from la ilaha illallah?

The subtext of all discussions regarding Islamophobia, in all contexts – what itself remains tacit and in between the lines – is the idea that prejudice against Muslims is justified, and.. well… kind of understandable. What place does the conceptual, nefarious Muslim have in liberal democratic societies? Muslims are asking for it – aren’t they?

Preventing Parenting

The ideological impact of culture and media in constructing the villainous Muslim in popular consciousness – and crucially in Muslim consciousness – has been great, but the punitive impact of domestic counter-terrorism regimes and their role in policing Muslim communities has also caused untold material damage to Muslim communities and their relationship to Islam. We see efforts from European governments to amalgamate Muslims with terrorism and to continue to problematize hallmarks of Muslim identity. It seems here the neo-Imperial agenda of the surveillance state, ironically, has more in common with extreme ‘Islamist’ groups than those Muslims it seeks to incriminate as such, by fueling feelings of disenfranchisement and exclusion. Here we see ISIS and European governments working hand in glove.

While youthful embarrassment is one thing, this perceived threat and cultivated shame take on a whole new dimension once you are a parent. Those culturally cultivated feelings of shame are underpinned by a very real and material threat to our status as guardians and our very connection with our children. While we can laugh at the wudu stories, what of every parents’ worst fear, and a possibility that hangs heavy in the air for Muslim parents – that of losing your child for appearing too ‘Muslim’. For them saying the ‘wrong’ thing for a Muslim child, at the doctor’s office or while chasing their friends in the playground. This threatens to further distort our understanding and relationship with our belief system, and crucially future expressions of it.

The Muslim Family as Frankenstein

The moral panic that certain Islamic practices hold has seeped into Muslim consciousness and imbued certain noble practices with shame, and this is something we need to actively seek to discontinue in ourselves, in redressing our own notions of what it means to be both British and Muslim. Being mindful of how public perceptions of Muslims and Islam inform our subconscious and conscious parenting is potentially the most conducive thing we can do as bestowers of Islam for the next generation of Muslims. Our athan-clock is now our children and their own public expressions of Muslimness, and how we respond to this is crucial. How we might shy away from public expressions of faith, how we might casually dissuade our children from wanting to wear Islamic dress to the local park.

Creating New Norms

Breaking this chain of shame and disesteem in Islam is key to not warping our children’s delicate and evolving impressions of our religion, and discontinuing inter-generational, internalized Islamophobia. It is key to situating their Islamic identity in the local and immediate: strengthening their British, Islamic identity and allowing them to practically and guiltlessly apply it to their everyday.

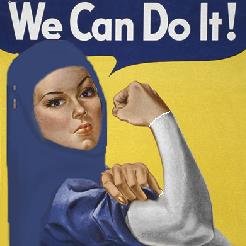

As parents, we need to disentangle our noble faith from the web of misconstruction and fallacy to which we have intimately tied it. We must take time to dismantle the hijab and beard from danger and threat in our thinking and unpack Islamic values and practices from their closeted and illegitimate anchors. Identity and representation are linked in a symbiotic way – the way we are seen by others, if left un-interrogated, determines how we see ourselves. We need to un-root the feelings of illicitness and shame so we are able to present and live Islam in an unfiltered way for ourselves and our children.

A New Language

We must begin to create our own language that no longer privileges prevailing norms, or which are entirely reactive against them. This is not a tired and hackneyed call to challenge stereotypes, because we don’t need to reinforce them by simply and unquestioningly inverting them, rather than questioning the assumptions that underpin them with nuance. We are constantly witnessing examples of how limited our vernacular is as British Muslims – the most recent example being of the Zara Mohamed, BBC Woman’s Hour interview. While Zara responded with admirable grace, what was telling about this exchange, was there was absolutely no linguistic space for a conversation about gender and religion outside of the language and power structures we are borrowing from secular standards. The option of critically speaking about men leading salah did not exist given the asymmetry in gender relations in Western patriarchy, which are constantly imposed on Islam, and the linguistic framework we have inherited as a result. We must reclaim terms such as modesty, chastity and humility and recast them in the gender-neutral, universal light in which they’ve always been intended in Islam rather than parroting secular gender norms. We must try not to shy away from basic tenets of our faith, inheriting hang-ups from mainstream culture, because as we all know there is hikmah and barakah in all of it.

We must reclaim terms such as modesty, chastity and humility and recast them in the gender-neutral, universal light in which they’ve always been intended in Islam rather than parroting secular gender norms.Click To TweetOur Own Narrative

We must no longer base our instinctive understanding, or thinking, of Islam on secular, mainstream narratives. When we look at staples of British Muslim culture, we see continual examples of how we have internalized someone else’s narrative regarding our own religion. Take the domed mosques which have come to characterize early British Muslim architecture, but which were first designed by non-Muslim architects, based on Orientalist tropes, and unquestioningly embraced as symbols of British Islam by the community.

Thinking Critically

Furthermore, we must adopt a more frank understanding of this capitalist value system which relegates Islamic values, and be able to engage with the building blocks of that value system in a more critical way. Mass culture is engineered entirely on the profit motive and a culture that casts shame upon Islam does so because it cannot profiteer from it or use it to line its own pockets.

We must be able to situate wider culture within its context. To understand that the Netflix culture obsessed with unveiling Muslim women exposes more about its own the reductive view of women in media – a clear indication that they feel audiences would not be interested unless women are visually available, and which is clearly uncomfortable with portraying women outside of a, frankly, reductive and damaging beauty standard. Remember that the construction of the Monster in popular consciousness reveals more about those that fashion the image of Monster than those who are fashioned as it. This is a culture war which we have no part in, and which secular liberalism appears to be having with itself, we do not need to be caught in the crossfire.

We need to unpack our own prejudices concerning religious practice by not constantly demoting it intellectually, by probing the classist assumptions through which we see it. We seem to have created our own conveyor belt model which links Islamic orthodoxy to lower class and IQ, and which sadly stems from the material fact that, as a young and developing community, nearly 50% of British Muslims live below the poverty line. This snobbery is based on the wider Islamophobic model and is designed to breed a sense of complacency in liberal Muslims, undermining solidarity across the Ummah. Furthermore, it has no place in Islamic values which rejects the pretensions of elitism.

Centering Allah

We need to replace the omnipresent voice of secular, Islamophobic thinking in our head with a sense of taqwa – centering Allah

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Mariya bint Rehan is a 34-year-old mother, author, and illustrator from London. Mariya has written and illustrated her first children’s picture book called The Best Dua. She writes on a range of issues concerning Muslim identity and parenting and has a background in development and policy in the voluntary sector. She can be found on Instagram @muswellbooks and via her website www.muswellbooks.com

Faith, Identity, And Resistance Among Black Muslim Students

Moonshot [Part 12] – November Evans

From The Prophets To Karbala: The Timeless Lessons Of Ashura For Muslims Today

Moonshot [Part 11] – The Fig Factory

Nationalism And Its Kurdish Discontents [Part II of II]: Kurds And Turkiye After Ottoman Rule

Moonshot [Part 11] – The Fig Factory

Moonshot [Part 12] – November Evans

Moonshot [Part 10] – The Marco Polo

Moonshot [Part 9] – A Religion For Real Life

Genocidal Israel Escalates With Assault On Iran

[Dhul Hijjah Series] Calling Upon the Divine: The Art of Du’a (Part 1)

IOK Ramadan 2025: Four Steps | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Do Your Best | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Giving Preference to Others | Sh Zaid Khan

Aisha Sara Ilott

May 31, 2021 at 6:28 PM

Salam Alaikum,

Masha’ Allah sister. Thank you for writing this article and may Allah reward you!

My Father is an English revert and Mother is Sudanese. I was raised mostly in Sudan where I attended private English schools. I can tell you even while living in a Muslim-majority country I have seen fellow Muslim’s internalised islamophobia. At school if you were “too religious” then you would be seen as strange or uncool. Having more western sensibilities was favoured. I was never really on the receiving end of this negativity, but I believe that was due to the fact that my Father is a blond-haired, blue-eyed westerner. I guess I was deemed western enough.

Now having moved to the UK to complete my secondary education and attend university, I was able to experience a different type of islamophobia. I would say that British islamophobia/racism in everyday life tends to be quite subtle, however, the effect on Muslims is blatant. As you wrote in your article, there is a deep underlying shame in our “Muslimness” which I think manifests differently in boys and girls.

Your article has given me a lot of food for thought! So thank you once again.

Yours sincerely,

Aisha Sara Ilott