#Islam

The Study Quran: A Review

Published

By

Mobeen Vaid

The Study Quran: A Review[1]

Introduction

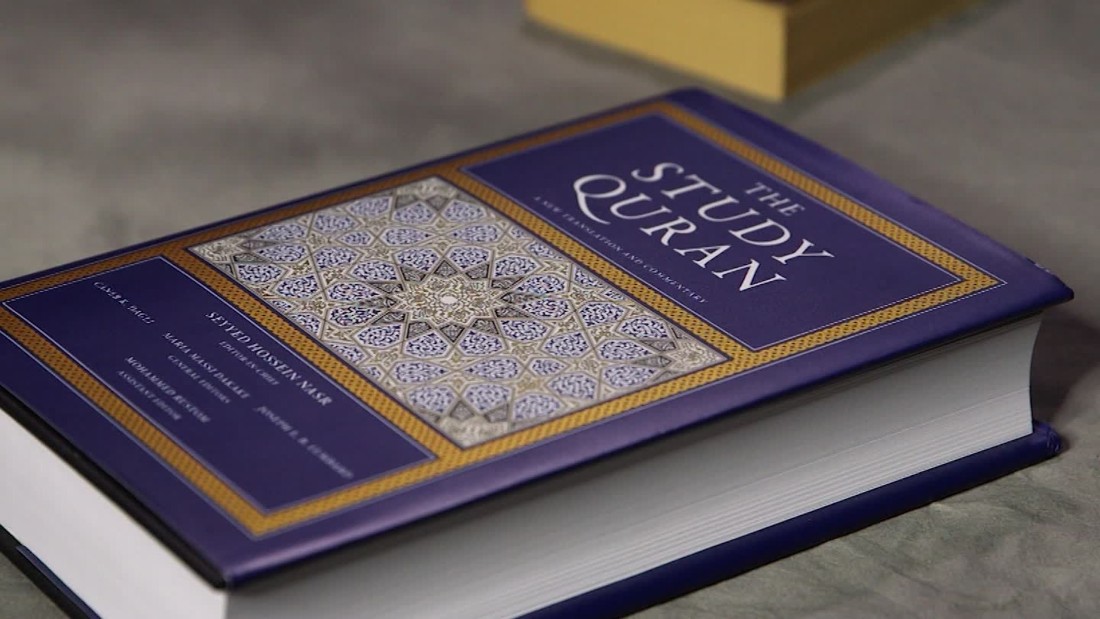

The Study Quran (SQ), a project of HarperCollins, can perhaps best be understood as an analog to its forerunner, the HarperCollins Study Bible. Originally published in 1993, the SB is an ecumenical project. Though various denominational actors and figures are cited, the SB bears no preference for one over another. Aside from its denominational accommodations, the SB is significant as an academic project – entry level courses in academic institutions teaching the Bible or Christianity routinely mandate the SB as required reading. As a result of its widespread use in academia, the SB has sold quite well, having exceeded 150,000 copies since initial publication. Therefore, although the SB may not hold much currency within devotional congregations, it retains a majority market share in academic environments.

Like the SB, the SQ is also an ecumenical work. The authors, a team of Islamic studies scholars led by Seyyed Hossein Nasr include Caner K. Dagli, Maria Massi Dakake, Joseph E.B. Lumbard, and Mohammed Rustom, account for both Shiite and Sunni perspectives when offering exegetical commentary and translating verses (see, for example, SQ commentary on Q 33.33), and have maintained translations of creed that can mutually support the various theological orientations that predominate in mainline Islamic thought (Atharī, Ash‘arī, Māturidī, and Mu‘tazilī). In addition to its ecumenicism, the SQ will likely become a bona fide standard for Islamic Studies courses in academic institutions throughout the world. Unlike the SB, the SQ enters an arena in which alternatives are sparse. Instructors have long struggled to provide accessible translations of the Quran, let alone commentaries that provide meaningful insight corresponding to seemingly ambiguous and otherwise difficult passages found in the Quran.

Quran Translations[2]: The Current Landscape

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

The challenge to provide accessible translations of the Quran has not been unique to academic environments. Originally published in 1934, Abdullah Yusuf Ali’s The Holy Qur’an: Translation and Commentary became a de facto standard in English-speaking communities well into the 90s. Though useful as an early translation, Yusuf Ali’s work was fraught with problems. The language of Yusuf Ali’s translation mimicked Victorian prose, employing terms that were not comprehensible to the majority of congregants. In addition to the linguistic shortcomings, the footnotes contained serious errors, particularly in earlier versions (later revisions eliminated much, though not all, of the truly egregious content). Finding alternatives, of course, was not easy back then. The most available alternative was perhaps Pickthall’s The Meaning of the Glorious Koran. Unfortunately, Pickthall, like Yusuf Ali, suffered from what Khaleel Mohammed described as “archaic prose and lack of annotation” (see Muhammad, 2005).

Over the past decade better translations have emerged, though few have gained serious resonance within the Muslim Community. Though not a particularly recent translation, Muhammad Asad’s The Message of the Qur’an has experienced broader adoption as of late, especially within the context of outreach. Despite its readable prose and accessible language, Asad’s translation contains explicit Mu‘tazilite bias resulting in gross interpolations and allegory in place of evident meanings. Take for example Q 13.27, which reads, “Now those who are bent on denying the truth [of the Prophet’s message] say, “Why has no miraculous sign ever been bestowed upon him from on high by his Sustainer?” Say: “Behold, God lets go astray him who wills [to go astray], just as He guides unto Himself all who turn unto Him”.” Notice here a few features of Asad’s translation – al-ladhīna kafarū is translated as “those who are bent on denying the truth,” instead of the more conventional “those who disbelieve.” This is not a mere terminological difference, but a theological distinction which I expect specialists in the field of theology to identify immediately. Perhaps even more meaningful is how yuḍillu man yashā’ has been translated – “God lets go astray him who wills [to go astray]” (emphasis mine) – an interpretation keeping with Asad’s Mu‘tazilite predilections. Elsewhere, Asad translates fa-zāda-humu l-lāhu maraḍā in Q 2.10 as, “so God lets their disease increase” (emphasis mine). These are not isolated incidents – miracles, any issue related to qadr, how ‘adl manifests and related items are frequently situated within a Mu‘tazilite worldview, rendering it problematic for the majority of Sunni congregations.

Another recent yet problematic translation of the Quran is Muhammad Taqi-ud-Din Al-Hilali and Muhammad Muhsin Khan’s The Noble Quran. Subsidized by the government of Saudi Arabia, copies of The Noble Quran can be commonly found in mosques both domestically and overseas. Unfortunately, the Hilali-Khan translation suffers from egregious errors and interpolations, advancing a particular orientation of Islam directly within the translation itself. Wherein prior translators largely constrained their efforts to translating the texts and footnoting their biases, like Asad, Hilali-Khan elected to interpose those biases directly into the translated words, making the distinction between God’s words and their own quite difficult. That many instances of interpolation repudiate Christianity and Judaism has not gone unnoticed, with Robert Crane referring to it as “perhaps the most extremist translation ever made.”

Two less problematic recent translation attempts include M.A.S. Abdel-Haleem’s The Qur’an, A New Translation, and Aminah Assami’s Saheeh International The Qur’an: English Meanings (accessible at quran.com). Both provide cogent, readable prose, and have largely refrained from incorporating denominational biases within the actual translation itself, though of course neither is perfect and there remains significant room for improvement. Some have alleged the Saheeh International translation as being little more than a recension of the Hilali-Khan translation sans doctrinaire. This allegation is not altogether untrue – translations such as, “And Our angels are nearer to him than you, but you do not see,” (emphasis mine) to verse Q 56.85 are indeed problematic. In the verse, the pronoun naḥnu (we) is translated as “Our angels”, in direct contrast with the literal meaning of the term. Though certain premodern commentators have interpreted naḥnu as referring to the angels, a direct translation would not render that meaning on its own. Due to this and other instances of interpolation, those with sensitivities to denominational impositions will likely prefer Abdel-Haleem’s translation.

All of this, of course, is to say nothing about the category of exegesis which is far less developed than translation. Few exegetical works have been translated to English, and those that have are often summarized with their own, often copious shortcomings. In this regard, the dearth of available vehicles through which inquiring minds can learn about the Quran and its meanings is palpable. For this reason, the SQ is not merely a contribution likely to take hold within secular academia, but lay believers as well, and the early reception to the SQ has certainly reflected that vacuum.

Features and Overview of the SQ

The SQ approaches 2,000 pages in full. It is, according to the authors, the product of a decade of work, and the academic rigor is apparent after even a cursory reading. The exegetical commentary of the SQ references forty-one commentaries in total, with medieval commentaries constituting the predominant points of reference. Of the commentators cited, Ibn ‘Āshūr and Ṭabāṭabā’ī are the most recent (both authors having died in the 20th century).

The book has many strengths. For one, the SQ incorporates prophetic traditions (ḥadīth) into the commentary, something that I suspect will not please structural reformists who anchor their efforts in a Quran-only epistemology. In addition, the SQ is not a work colored by the ideologies and agendas of secular liberalism (in its many forms). It makes no apologies for verses that appear inegalitarian, malevolent, or otherwise discordant with the metaphysical commitments of contemporary liberal society. Instead, the SQ contextualizes, elucidates the tradition, and offers an understanding of those verses within terms that the Muslim community (or at least some portion of it) has understood them for over a thousand years. This, I suspect as well, will not gratify reformists who view the majority of premodern jurists and theologians as having been prejudiced by patriarchy, exclusivism, and militarism.

For example, the commentary of Q 4.11, a somewhat controversial verse given its prescription for inequitable distribution of inheritance between men and women, explicates traditional inheritance law and does not reinterpret or historicize the apportioning of inheritance. The SQ explains that the inequitable apportioning of inheritance can be attributed to the males provider-responsibility within a household, a reasoning cited from the exegetical work of Ibn Kathīr. The commentary does not belabor the point, nor engage in apologetics. The explanation of Q. 4.11 alone makes reference to the exegetical works of Ṭabarī, Qurṭubī, Ibn Kathīr, Wāḥidī, Zamakhsharī and Ṭabrisī who is cited for the purpose of incorporating Shiite interpretations of the verse.

A similar approach can be seen in the explanation of Q 4.34, the infamous verse of nushūz. Again, the authors cite premodern jurists, expound upon the occasion of revelation (sabab nuzūl), and provide stipulations that premodern jurists would articulate when commenting on the very controversial locution ḍarb, or striking. Of note is that the authors do not adopt an alternative explanation or translation of ḍarb, electing instead for a hermeneutic of fideism to the tradition.

Adam, the genealogical father of man, the first of creation, and a prophet of God is created ex nihilo, miraculously from dust, and not reenvisioned in light of Darwinian macroevolution (see commentary on Q 2.30-37, 3.59, and others). The ḥūr ‘īn, or wide-eyed maidens of the Garden, are appropriately presented as otherworldly figures in the commentary of Q 56.22. Having been imparted to the general public via a medium of radicalism/extremism, the SQ authors do a good job of reconfiguring the discourse around the topic of the ḥūr from one that is predominantly sensual/erotic to one that is part of a realm that God described as that which “no eye has seen and no ear has heard and what has not occurred to the heart of any human being.”

The exegetical commentary of Q 13.11 explains the axiom, “Truly God alters not what is in a people until they alter what is in themselves,” as an imperative to individually reform. Premodern exegetes took this verse as an indication of how God’s blessings in this life, such as health and wealth, are contingent on ones obedience to God, which stands as a far cry from the more common revolutionary connotations with which it is deployed today.

The story of Lot is as well consistent with the premodern narrative concerning the sins of Sodom. Commentary on Q 29.28-29 explains that although “some maintain that Lot reproaches them [i.e. his people] for forcible rather than consensual sexual relations,” the “emphasis here and in 7:81; 26:165-166; and 27:54 is upon approaching men with desire and lust, whether consensual or not.” The consensual/forcible framing is a common one among those arguing for an interpretation of Islam that admits LGBT sexual relations as religiously lawful. Central to the argument of LGBT in Islam advocates is a Quran-only reading, concluding that the people of Sodom were in fact guilty of pederasty, rape, or in certain instances, highway robbery, and that their sexual orientation was made issue by later scholars prejudiced by heteronormative sensibilities. As the SQ authors rightly conclude, a Quranic reading of Sodom provides no such indications.

In many instances, the SQ provides lucid, powerful commentary on verses related to the hereafter, repentance, virtue, and self-discipline. There are few texts that so seamlessly integrate spirituality (tazkiya and taṣawwuf), eschatology, intricacies of juristic disagreement, and creed in one place. Take, for example, commentary on the Chapter of Joseph (Sūrah Yūsuf), which brings together biblical references alongside exhortations deriding envy, advocating persistence and patience, the palliative power of prayer, and familial solidarity. The SQ authors take no creative license in this exercise, but rather draw from the copious medieval and modern commentaries relevant insights that animate the content of the chapter in ways that other books simply don’t. Whether one is able to appreciate the painstaking research that must have gone into producing this work or not, a non-Muslim accessing the SQ as an entry-point for learning about Islam may in fact maintain their prior prejudices, but cannot conclude that Islam as a religion, and the Quran in particular, is a simplistic, irrational, malevolent, or univocal tradition from its content. This, if nothing else, merits considerable praise.

Points of Caution

All of the aforementioned said, there are reasons to be cautious. The SQ is an academic and educational work, and as such includes commentaries from sources that may not be considered orthodox depending on ones denominational orientation. This includes elaborating views on creed that do not comport with either the Atharī, Ash‘arī, or Māturidī Sunni mainstream. Some of the Sufi commentaries can come off as uncomfortably esoteric. Khārijite positions are occasionally expounded upon, and not for the purpose of refutation. Some will also find the inclusion of an essay by Ahmed el-Tayyib, the current Grand Imam of Azhar and Mubarak/Sissi loyalist who supported the overthrow of Mohamed Morsi, discomfiting, though it should be noted that the essay predates the 2011 Egyptian uprising.

The SQ’s commentary is commensurate with the conventions of secular academia. How that manifests is not always clear to common Muslims, but there are significant implications to the way in which language is employed. For example, when one refers to the self-referential nature of the Quran, or the way in which ‘the Quran teaches us’ something, the Quran is treated as an object, with its own voice. This taxonomy is deployed by academics to avoid making an ontological claim. By contrast, for believers, the Quran doesn’t say anything, God does. When we attend sermons, imams tell us what God says – it is God who proscribes, permits, ordains, praises, and condemns. Although such language is appropriate and necessary for those who do not affirm the divine ontology of the Quran (a not altogether insignificant constituent of the SQ) or work within contexts which do not permit overt confessional faith commitments, one should be careful not to internalize that language within confessional contexts and communities. As Muslims we believe in God and His Words, a statement that is not readily accepted in popular culture.

Early critics have challenged legal rulings attributed to various madhāhib elucidated in the SQ as either not the dominant view within the school or misattributions. Though the SQ catalogs ḥadīth citations and exegetical commentaries, no such citations are provided for legal positions. Referencing source works for legal attributions would help to abate these criticisms, and one should consult a schooled teacher or imam for definitive positions within a particular legal school.

The SQ is a reference work, one that Muslims working in academic contexts will have to engage with. Students and lay congregation members pursuing ṭalab al-‘ilm should take consult with a reliable teacher as to whether it is advisable to study, and if so, how. Put plainly, Muslim readers should not expect the SQ to inform their beliefs about orthodox Islam.

Departing from Consensus

The Case of rajm

There are, of course, more serious concerns. Verses explicating ḥadd punishments, such as Q 5.38, are not avoided or explained away. Instead, communitarian benefits are articulated, destabilizing effects of wrongs examined, and premodern exegetes referenced. The more difficult case of zinā in Q 24.2 is a notable departure from this general heuristic, with the SQ authors opting to entertain a rather murky hermeneutic and call into question the juristic consensus related to the issue of rajm. In this regard, the authors initially mention the four principle prophetic traditions concerning rajm, but later purport “inconsistencies” and “incongruities” between them based on details within the disparate reports. In addition, the authors attend to the question of naskh, both with regard to the abrogated āyah of rajm as well as the question of the sunna abrogating the Quran and whether or not non-mutawātir reports are sufficient for overturning clear, unambiguous Quranic prescriptions.

There are a number of issues with this hermeneutic that I will try to synthesize here. Firstly, and most simply, is that rajm for zinā has been part of the juristic consensus since the inception of Islam (the Muhammadan variety). There is little debate that it was carried out by the Prophet

Third, the “incongruities” referred to are forced upon the various traditions. For example, in comparing the opportunities to recant afforded to the male adulterer with the Jewish couple to whom the Prophet (pbuh) extended no such opportunity, the Prophet (pbuh) may have felt reluctant to offer leniency out of fealty to the already extant rabbinic authority. As is mentioned in the tradition concerning the Jewish couple, the Prophet (pbuh) requested a copy of the Torah and adjudicated based on the content of their tradition, not his. The Jewish couple tradition mentions the couple as approaching the Prophet

Fourth, the issue of naskh al-tilāwah, although important, is not the central legal issue in determining the applicability of rajm. Even in the absence of the abrogated verse, the multitude of prophetic traditions, practice and statements of the Companions, and juristic consensus forms a sufficient corpus to evidentiarily support rajm. Though the more contentious topic of naskh is an important one and certainly a salient consideration for this verse, the prophetic practice is definitive in its application of rajm. Fifth, the aḥādīth of rajm do not abrogate the verses stipulating jaldah, but rather delimit them to unmarried individuals. Finally, although the SQ mentions rajm as “a more grievous punishment than all others mentioned in the Quran,” that distinction almost certainly belongs to the punishment for ḥirābah in Q 5.33.

This is merely an expounding of the premodern consensus, but says nothing as to how Muslim communities should wrestle with these traditions today. Some modern jurists have called for a moratorium on the ḥudūd altogether, and others have specifically called for a revisitation of the specific ḥadd related to zinā due to unfortunate abuses, honor killings, and other misapplications that have resulted in the deaths of many innocent lives. This is not a trivial matter, and I hope the above defense of rajm’s place in the tradition does not come off insensitive or tone-deaf to those problems. Nonetheless, any earnest effort to address current abuses will have to take the tradition and its evidences into account, something the SQ fell short of demonstrating.

Soteriological Pluralism[3] in the SQ

An even more problematic concern is with the SQ’s pluralistic commitments. Upon release, critical reception of the SQ fixated almost exclusively upon the pluralist advances of the SQ, responding most pointedly to an essay in the SQ authored by Joseph Lumbard entitled The Quranic View of Sacred History and Other Religions. After reading social media vituperation over the inclusion of pluralist soteriological commitments, my initial suspicion was that such a reading was overstating the pluralist overtones, preoccupied with an essay in the back of the book and perhaps curious interpretations of verses Q 3.84-85. Though this was somewhat true, critics were not altogether wrong in begrudging the multiple areas in which pluralistic interpretations are forced into passages that do not ostensibly support them and have never been maintained as such within the tradition. What follows will again be an attempt to synthesize the primary arguments averred by the SQ authors within the exegetical commentary itself while also paying heed to a few arguments in the Lumbard essay. The primary arguments in the SQ concerning this topic are as follows:

- Q 5.73 rebuts Monophysite Christology and not Chalcedonian Christology. Non-Chalcedonian Christological orientations are presented on multiple occasions as the focus of the Quran.

- Q 2.79 and elsewhere are not speaking about the Kitābī Also, the sacred texts of the Kitābī traditions have not been excessively altered.

- Q 2.62 is the primary verse, serving as a rule for the salvific efficacy of other traditions. More critical verses addressing other traditions should be subsumed beneath Q 2.62.

- Q 3.84-85 and elsewhere speak to a general, universal “islam,” or submission, and not to the specific “Islam” characterized by Muhammad’s (pbuh) prophethood.

With respect to the Trinity, the SQ maintains in multiple places that orthodox Chalcedonian Christology is not the subject of God’s reprimand in the Quran, but rather exaggerated forms of the Trinity are, namely, Monophysite Christology (‘exaggerated’ being an argument extended from Q 4.171 which reproaches the ahl al-kitāb for exaggerating (taghlū) in their religion). Although the SQ does in fact state that the tradition largely considers a unicity of God with three hypostases as incommensurable with the theology of Islam, a grievous error, and a major sin, in other places it delimits criticism to non-Chalcedonian Christology and largely creates a distinction between a Trinity with three hypostases and shirk, alleging the former to not necessarily constitute the latter.

In the commentary of Q 4.171 and Q 5.73 it is stated that “the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity as three “persons,” or hypostases, “within” the One God is not explicitly referenced, and the criticism seems directed at those who assert the existence of three distinct “gods,” an idea that Christians themselves reject.” Later, the commentary states that “Islamic Law never considered Christians to be “idolaters” (mushrikūn) and accepted Christians’ own assertion of monotheistic belief.” In certain instances, the SQ portrays Chalcedonian Christology as a minority, or at the least, largely misunderstood/unknown during the formative period of Islam.

Although medieval Eastern Christianity was more complex than the current post-Niceno-Constantinopolitan theology which dominates today, Chalcedonian Christianity was not altogether uncommon and there is little reason to assume the early Muslim community to be somehow unaware of its presence and beliefs. The essential criticisms of the Quran include attributing divinity to Christ, a child to God, and belief in a Trinity. There is no scholar in Islamic history, which I am aware of, that provided a concession for one Christological orientation over another, and exposure to Melkite Churches and its concomitant beliefs existed from the earliest days of Islam.

The earliest Christian apologetic text in Arabic to address Islam was a manuscript entitled On the Triune Nature of God (Fī tathlīth Allāh al-Wāḥid) by an unknown author (loosely dated to the early/mid-8th century). In it, the author goes to great pains to emphasize that Christian theological commitments are not of three separate “gods”, but of a single God with multiple states. One can assume that this means that in the formative period, Chalcedonian Christology was not being treated any differently than other forms of Christology, and the earliest Muslims regarded it as constituting the very Trinity which the Quran rebukes. Another early Christian writing which is largely a polemic against Islam is John of Damascus’ (656-749) Fount of Knowledge. A Chalcedonian Christian, John characterizes Muslim belief as follows:

“He says that there is one God, creator of all things, who has neither been begotten nor has begotten. He says that the Christ is the Word of God and His Spirit, but a creature and a servant, and that He was begotten, without seed, of Mary the sister of Moses and Aaron. For, he says, the Word and God and the Spirit entered into Mary and she brought forth Jesus, who was a prophet and servant of God. And he says that the Jews wanted to crucify Him in violation of the law, and that they seized His shadow and crucified this. But the Christ Himself was not crucified, he says, nor did He die, for God out of His love for Him took Him to Himself into heaven. And he says this, that when the Christ had ascended into heaven God asked Him: ‘O Jesus, didst thou say: “I am the Son of God and God”?’ And Jesus, he says, answered: ‘Be merciful to me, Lord. Thou knowest that I did not say this and that I did not scorn to be thy servant. But sinful men have written that I made this statement, and they have lied about me and have fallen into error.’ And God answered and said to Him: ‘I know that thou didst not say this word.”

Of note above is John’s characterizing of Islam’s conception of God against the Trinity (note that elsewhere in Fount John argues time and again for Jesus being consubstantial with God, in contrast to his Muslim interlocutors). John’s location in the first century of Islam is critical, as his understanding is largely being informed by information imparted by the Companions unto early converts. In this regard, John describes Muhammad

Therefore, one has to conclude that if God were addressing only certain Christological orientations and not others, or that it only explicitly called out three separate “gods” but not “states” or hypostases, then that nuance was either missed by the early Muslim community, or the early Muslim community succumbed to religious chauvinism and simply disregarded its otherwise ecumenical nature. The distinction between the legal categories of ahl al-kitāb of mishrikūn does not mean that one cannot simultaneously be another. Indeed, anything that derogates from the unicity of God constitutes a type of shirk, let alone a belief in a godhead with three concurrent states, one of which is believed to be the son of God.

In the commentary of Q 2.62, attention is paid to the case of one who hears about Islam, but encounters obstacles that prevent Islam from taking hold. The SQ cites al-Ghazzālī’s work Fayṣal al-tafriqah which speaks of the ‘unreached’, an excuse that was admittedly more plausible in premodern societies. Theologians have long incorporated such individuals into the category of ‘excused’ from immediately being subject to chastisement, in keeping with Q 17.15 “We do not punish until We have sent a messenger.” How the notion of ‘unreached’ translates to those whose only exposure to Islam is via the medium of hostility and antagonism, only God Knows.

Though one may argue that soteriological pluralism is ancillary to the overall project of the SQ or somehow constitutive of a fraction of the two-thousand page oeuvre, the reality is that pluralist references are almost impossible to miss. Many verses that repudiate Christian or Jewish doctrine are reinterpreted or historicized. Salvific efficacy is extended to all religions and paths, so long as they are somehow subsumed under the general postulate “islam”, instead of the particularized Muhammadan “Islam” (capital “I”). In this regard, belief in the Prophet

Such an understanding of soteriology is almost impossible to support within a full reading of the Quran, and certainly impossible after taking into account the less accommodating ḥadīth tradition which contains unambiguous reports such as, “By the One in Whose hand is the soul of Muhammad, there is no one among this nation, Jew or Christian, who hears of me and dies without believing in that with which I have been sent, but he will be one of the people of the Fire.” Verses repudiating the Kitābī traditions are not scant – they compose a major constituent of the Quran, including extensive passages in Baqarah, Āl-‘Imrān, al-Nisā’, and Mā’idah. They include critiques of Kitābī theology, ecclesiastic authorities, alterations of sacred texts, and implores the ahl al-kitāb to submit to the message of the Quran and the Prophet

Conclusion

The current landscape of Quran exegesis in English to date has not had much to offer non-Muslims and Muslims born in western lands seeking to learn about the Quran. As a result, inquiring minds have been relegated to unreliable, often simplistic, web sites responding to “hot button” issues within a very particular theological/denominational persuasion. Consequently, the intellectual legacy of Islam has largely gone unappreciated outside of specialist circles. For many lay Muslims, scholastic discordance has been perceived as an exceptional circumstance, disagreement portrayed as regrettably derogating from an unrealistic ideal of unity, and theological polarizations the norm. Lost in the myriad challenges associated with inaccessible literature about the Quran has been the increasingly perverse portrayal of Islam and the Quran in the minds of the general public.

The presence in recent years of more intelligible Quran translations has surely helped, but accompanying commentaries remain nonexistent. Within this context, the SQ is a monumental contribution to the field of Quran studies, offering perhaps the first proper exegetical work on the Quran in the English language. Anchored in a traditionalist narrative accumulated over a thousand years, the SQ has coalesced the views of luminaries and theologians from disparate theological orientations and denominations. Although it is not the “final word on a whole tradition”, as Caner Dagli remarked in response to early critics, it certainly provides appreciable insight into a sophisticated, multi-dimensional tradition which has come to formulate how Islam is conceptualized today.

The SQ has regrettable instances in which it has departed from consensus, namely, with respect to rajm and soteriological pluralism. In both cases, traditional theological methodologies have been jettisoned in favor of extenuating considerations and questionable heuristics that contradict normative orthodox religious teachings. Despite these legitimate and important concerns, I think we would all agree that policy makers, non-Muslims interested in Islam, Muslims distant from their faith, and universities making use of the SQ is preferable to the overwhelming majority of content related to the Quran today. In that vein, we are certainly in its authors debt. May God remunerate their efforts abundantly, and guide them and us to what pleases Him. Ameen.

And God Knows Best.

[1] I gratefully acknowledge the feedback from the SQ authors in support of this piece. Their insights and feedback has animated this review in important ways. Though some of the critiques in this article are not favorable in reviewing certain topics in the SQ, I have found the authors themselves to be nothing other than genuine, open to dialogue, and very interested in furthering conversations that have been generated since the SQ’s release.

[2] Translations, by definition, are subject to the shortcomings inherent in attempting to convey meanings from one language to another. The case of the Quran presents more complications than most – ‘clean’ equivalents are not always available for certain terms, let alone the stylistic, rhetorical, and linguistic features native to Quranic passages. Ultimately, this requires interstitial commentary and interpretive decisions, many of which are non-trivial. The term “translation”’ can, therefore, be somewhat misleading. A more candid nomenclature would be ‘an interpretation of the Quran’s meaning.’ See Some Linguistic Difficulties in Translating the Holy Quran from Arabic into English (Brakhw, 2012) for a more detailed treatment of the topic.

[3] Though much of the social media fervor has employed the term perennialism, pluralism is, in fact, a more accurate term to denote the extending of salvific efficacy to diverse faith traditions. Though particular perennialist orientations may accord a pluralist soteriology, one does not necessitate the other.

Glossary:

Eschatology -a branch of theology concerned with the final events in the history of the world or of humankind

Esoteric- relating to or being a small group with specialized knowledge or interests

Salvific- having the intent or power to save or redeem

Soteriology- the branch of theology dealing with the nature and means of salvation

Perennialism-is a term referring to a number of 20th century writers who rejected modernity and argued for a return to the perennial truths as preserved in the traditions of the world religions. Though perennialists often view each of the world’s religious traditions as sharing a single, universal truth on which foundation all religious knowledge and doctrine has grown, they do not immediately accord salvation to all faiths, nor do they necessarily consider all faiths valid.

Pluralism- pertains to diversity of religious belief systems co-existing in society. In this paper, it was used specifically to refer to the worldview that one’s religion is not the sole and exclusive source of truth.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Mobeen Vaid (MA Islamic Studies, Hartford Seminary) is a Muslim public intellectual and writer who focuses on how traditional Islamic frames of thinking intersect the modern world. He has authored a number of pieces on Islamic sexual and gender norms, including Can Islam Accommodate Homosexual Acts? Qur’anic Revisionism and the Case of Scott Kugle (MuslimMatters, 2017). Along with MuslimMatters, his other articles can be found on his Medium website Occasional Reflections

[Film Review] Time Hoppers: The Silk Road

The Comparison Trap | Night 5 with the Qur’an

Op-Ed: Can Zakat Be Used For Political Campaigning? An Argument In Favor

[Podcast] Faith, Fasting, and Metabolic Wellness with Dr. Saadia Mian

When You’re the Only Muslim in the Room | Night 4 with the Qur’an

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

[Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy

[Podcast] Guardians of the Tradition: Muslim Women & Islamic Education | Anse Tamara Gray

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

Op-Ed: Bitterness Prolonged – A Short History Of The Somaliland Dispute

The Comparison Trap | Night 5 with the Qur’an

When You’re the Only Muslim in the Room | Night 4 with the Qur’an

When Honoring Parents Feels Like Erasing Yourself | Night 3 with the Qur’an

5 Signs Your Teen is Struggling with Imposter Syndrome | Night 2 with the Qur’an

Who Am I Really? What Surat Al-‘Asr Teaches Muslim Teens About Identity | Night 1 with the Qur’an

Trending

-

#Current Affairs1 month ago

[Podcast] Should Muslims Ally with Conservatives or Progressives? | Imam Dawud Walid

-

#Current Affairs1 month ago

Op-Ed: From Pakistan To Gaza – Why Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan Terrifies Power And Zionism

-

#Islam4 weeks ago

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

-

#Life4 weeks ago

[Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy

Siraaj

December 14, 2015 at 5:43 PM

How is it possible to ignore the ijmaa’ of the community on something so fundamental as the salvific exclusivity of Muhammadan Islam is beyond me. It may sound exaggerated to say, but I find it more problematic than the AQ or IS interpretations. Beyond just mimicking the methodology of leaving the community for an offshoot interpretation, it poses a serious problems for those who use this book as a vehicle to understand islamic theology and would consider coming to it.

Mustafa Mahmud

December 14, 2015 at 9:18 PM

I will cut the pc nonsense and try to say something honest that won’t get filtered.

It’s a consensus of the fuqaha of the Ummah that this belief is not just some deviance but absolute blasphemy.

That we have imams willing to overlook that and recommend it anyways without explaining quite clearly, that this false view of salvation actually is something that expels someone from the fold of Islam. It’s not just false, it’s absolutely blasphemous. It EXPELS someone from the religion.

Scholars held someone who did not belief salah obligatory or thought sodomy to be halal as a nonbeliever.

In this day and age we have people failing to accept Islam as obligatory and considering kufr halal!!!

This is irja’ to the utmost extreme just like Daesh has taken takfir to the utmost extreme. In fact it’s absolute blasphemy.

And yes, calling someone who said the Shahadah a kaffir is a formal process done only by a Qadi in an Islamic State.

We can argue for these peoples(Perrenialists and their ilk) case in this life but who will argue for them before Allah?

That we are cautious with takfir is not some safeguard for them on yawm al Qiyaamah. It’s possible many heretics in this life are spared the sentence in this life only to have it in the next.

يَوْمَ تَبْيَضُّ وُجُوهٌ وَتَسْوَدُّ وُجُوهٌ ۚ فَأَمَّا الَّذِينَ اسْوَدَّتْ وُجُوهُهُمْ أَكَفَرْتُم بَعْدَ إِيمَانِكُمْ فَذُوقُوا الْعَذَابَ بِمَا كُنتُمْ تَكْفُرُونَ

Caner Dagli

December 18, 2015 at 8:55 AM

This is precisely the kind of irresponsible talk that is lamentable. You are committing takfir, which itself is forbidden to someone like yo because you have not read the book and moreover you are clearly an ignoramus. Your rant is filled with so many category errors it’s hard to know where to begin. Kufr is neither halal or haram. I’d really love to see the category of “qadi in an Islamic State” in any literature before the 20th century. You most certainly have no idea what he doctrine of irja is or how it relates to us. Amazingly, there are even more mistakes in what you wrote. If we are wrong, we are wrong in the right way, and if you are right, it is most certainly in the wrong way. You clearly have never even learned the most basic adab. It’s no sin to be ignorant, but it is to bandy ideas you heard about from some pamphlets and presume to pronounce takfir on people who have devoted their lives to what you claim to defend. Shame on you.

Adnan

December 18, 2015 at 5:58 PM

Salam Alaikum Dr Dagli,

Mahmud’s behavior and adab are well-known to readers of Muslim Matters. Leave him in peace with the words of Surah Furqan. And jazakallah khair for you and the other editors’ efforts on the SQ.

M.Mahmud

December 18, 2015 at 9:52 PM

[COMMENT REDACTED]

May Allah guide me and all of you. [Ameen]

Mj

December 24, 2015 at 1:20 AM

I pray God is More Merciful in His Judgement, then you were in yours.

M.Mahmud

February 3, 2016 at 2:50 PM

All the fuqaha are agreed on this.

Al-Qaadi ‘Ayyaad said: hence we regard as a kaafir everyone who follows a religion other than the religion of the Muslims, or who agrees with them, or who has doubts, or who says that their way is correct, even if he appears to be a Muslim and believes in Islam and that every other way is false, he is a kaafir

(Al-Shifaa’ bi Ta’reef Huqooq al-Mustafaa, 2/1071)

Iffat Idrees

December 14, 2015 at 10:03 PM

Has anyone ever read or reviewed “The Majestic Qur’an by Translation Committee Abdal Hakim Murad, Mostafa al-Badawi and Uthman Hutchinson”. Any opinions that would be beneficial. I know it is out of print but if it is a good translation maybe muslims in North America should try to get it reprinted and distributed.

I have a copy and personally I like the translation.

Mobeen Vaid

December 15, 2015 at 9:08 PM

I dont know if I would go as far as to say that it is more problematic than AQ or IS. That said, I dont disagree that salvific pluralism is indeed a major intellectual challenge that we will continue to engage in the coming years. The very idea of a single faith having a ‘monopoly’ on the truth or simply concluding other faiths are wrong is, within modern discourse, viewed as intolerant, judgmental, and at times, cast as extreme.

Rich Deen

December 29, 2015 at 5:55 AM

Nice review, and worth a good reread. I found the explanation of Q 122:3 in TSQ quite limiting.

Looking at the recent book ‘Between Heaven and Hell: Islam, Salvation, and the Fate of Others,’ the issue seems nuanced.

DI

December 14, 2015 at 10:21 PM

If a perennialist translated the Bible or Torah, Jews and Christians would be in uproar. But we Muslims are OK with this crazy group translating the Holy Qur’an? Subhana Allah.

We might as well let Scientologists translate the Qur’an now!

di.

ST

December 14, 2015 at 11:46 PM

How do you figure that the authors are perennialists? Not all or even most of them are…but you read that somewhere and ignorance is contagious.

Former translations of the Quran have been done by Christians, Bahoras, Shias, Qadiyanis …and people just read them because they have no idea. Then comes a group that dedicates a decade to a translation with commentary and we show how ignorant of a community we are because we jump on bandwagons without even reading the work.

This is to say nothing of the fact that if people were to read what is actually to be found in the original tafsirs (in Arabic and Persian) of all the orthodox authors they can think of….their jaws would drop to the ground at what they saw.

Question for you: how much of the SQ have you actually read?

I can’t wrap my mind around why so many people are caught up in commenting/reviewing such a MASSIVE work without having read a solid portion of it?!

M.Mahmud

December 14, 2015 at 11:55 PM

Past Muslim mufasiroon would never support Perrenialism as it is kufr. Perhaps if some of these ignorant laymen viewed the stunning agreement past generations had on the cursed fate of disbelievers their jaws would drop…..

TSQ very clearly promotes perrenialism. Ignorance spreads and so does denial.

[EDIT: Please stop the takfir]

Please do some thinking before hastily judging the scholars who rightfully condemned this deviated(to say the least) book. Islamic aqeeda is a lot more rigid and unflexible then people would like to believe. Intellectual depth is not the equivalent of flexibility. Allah only admits one group of people into Paradise-Muslims. And the definition of a Muslim was clearly known to the Sahaba and generations since.

asad

December 15, 2015 at 7:02 AM

This isn’t a “crazy group.” Before passing out ignorant comments, spend a few seconds flipping the pages to see the contributers. Among them is Muhammad Mustafa Azmi – a conservative deobandi scholar. Not all of the contributors are perennialists. And not all of the contributors would necessarily agree with each other. Putting this problematic issue aside, overall this is a good scholarly contribution.

Mobeen Vaid

December 15, 2015 at 9:11 PM

Salam DI,

I actually think you would be surprised. I havent read much of it, but would venture to guess the SB is largely pluralist in how it views salvation. Salvific pluralism has already entered Jewish and Christian communities long ago.

DI

December 16, 2015 at 12:16 PM

Wa aleikum salaam wa rahmatullahi wa barakatuhu,

I don’t think people are aware Seyyed Hosein Nasr is a student of Fritjof Schuon. [REDACTED]. Furthermore, Sufi groups have allowed perennialists to infiltrate their circles and they twist sayings of Rumi and Ibn Arabi to accord to a ‘everybody goes to heaven’ approach. They are like refugees from Ahlul Sunnah and take refuge in the soft-heartedness and gullibility of sufi mureeds. The reality is they are anathema to sufism and they hijack it for their own academic gains. Perennialist writings are hollow wordplay (“qatwil”) with a quasi-sufi veneer. It just bewitches people into thinking they have come across some great wisdom because of the big words, sentimentalism, borrowing Hindu and Christian concepts, italicized Arabic, but it always always always has zero substance on closer inspection. They pretend to be great sufis and co-opt sufi tradition, teach morality without action, are extremely arrogant and mix truth with 99 falsehoods. They are intoxicated by their own words and its really a type of poetry. You can tell it has little meaning when you compare it to the true meanings of Qur’an and Hadith. They prefer their strange ideas to the Haqq. What makes perennialism unique is they are a solely Western hizb with no roots in Muslim world, no takfir of them has been done nor has anybody ever debated them, even though all ulema recognize their heresy. Perennialist writings were stepping stones to Islam for many people, much like NOI, but also serve as a halfway house backwards into Christianity and misguided cults. But since perennialism has outlived its usefulness and because its infected tasawwuf circles and writings, we need to uproot perennialism.

I am aware of Imam Ghazali’s view in Faysal at-Tafriqa and it only applies to followers of Isa at his time, Musa at his time and the excuse for Ahlul Fatrah. THAT’S IT. We can dig through as much sunni literature as we want and try and make the Qur’an say what our universities and government want, but when it comes to soteriology, the most it all rises too is a “MAYBE” they are saved and on that we have no authority – only God has authority. No definite points. Dhann, doubt, speculation. And Islam is a system of law that does not accept such doubts as legal principles. We are misleading and become like shaytan who will say on the day of judgement to those he misguided, “I have no authority”.

There is a Hadith Qudsi to the effect, “I put this group in Hell and I have no care. I put this group in Heaven and I have no care.” (paraphrased). We forget Allah is our Lord – not our misplaced idealism. I want to also mention the verse which puts a closed door on our speculating “Ahum yaqsimuna rahmata rabbik – Do THEY distribute the mercy of your Lord?” (Qur’an, 43:32). We need to believe in this ayah and stop thinking we have any sway in the decision, WHOEVER we are. What Allah and His Rasul (salallahu alayhi wasalam) have said is where it stops.

When it comes to salvation, I find it amazing how easily everybody’s lips loosen up. The same people concerned about non-Muslims going to hell are never ever concerned about wrongful imprisonment or mass incarceration in the dunya. They simply like to tout a more ‘enlightened view’ (read: bastardized view) of Islam and think they are an educated elite. When it comes to the Qur’an mentioning Allah’s Throne, Hand, Face, we are taught to say, “We believe in it without asking how (bila kayf)’. But when it comes to His mercy we start to ask HOW? Why? Because we think we know and understand Mercy? We think we know better than Allah’s mercy? That’s the problem. Why do Muslims never say about Allah’s Mercy – “We believe in it without asking how that Mercy will manifest.” Hellfire and heaven – “We believe in it without asking how.” We forget there is a purpose to Hellfire and Heaven is to purify us through remembrance of the Akhira.

Lastly, we are very quick to forget Surah al-A’raf – the People of the Heights – Muslims whose good deeds and bad deeds will be equal and they will be reside on a wall between Heaven and Hell. They haven’t done anything more to deserve Allah’s Mercy than to deserve Allah’s Wrath and they haven’t done anything to deserve Allah’s Wrath more than they have done anything to deserve Allah’s Mercy. Allah decides – no one else. This is the teaching. If Allah mentioned this group – and the classical mufassir say People of al-A’raf enter Heaven LAST – and we know this group admonishes idolators before they enter Heaven – then where does that put all this soteriological speculation about other religions entering heaven?

I think this is also worth reading by Imam Dr. Shadee ElMasry on Safina Society website

(Dunno if my comment went through)

di.

Mj

December 24, 2015 at 1:32 AM

[GROW UP]

I certainly pray God is More Merciful in His Judgement, then you are with yours. [AMEEN]

Horizonwalker

December 14, 2015 at 11:20 PM

@Mobeen Vaid

Thank you for this great review! I do have one question.

In the beginning of the review you mentioned the weaknesses of the literal Arabic translations in other translations (interpretations) of the Quran.

However you didn’t explain this crucial point with regards to The Study Quran in this review. If you mentioned it, I couldn’t find it.

Your review on the commentary in The Study Quran is very useful.

And many Muslims will definitely be discouraged from reading the book based on the non-Traditional position on Salvation in the Afterlife.

*However *

If the translation of the Quran is really much better than other alternatives,

and if the layout makes a clear distinction between the literal translation of the ayat and the commentary of the scholars

which includes specifically showing the distinction between Sunni and Shia commentary,

this might convince and encourage Muslim who disagree with some of the commentary to read it

and recommend it to others.

(Hopefully to help Muslims from different denominations connect on the many issues they do have in common, while making clear the issues on which they respectfully differ).

* Is this the case for The Study Quran? *

Mobeen Vaid

December 15, 2015 at 9:26 PM

Salam Horizonwalker,

I have to concede that I am not a translation expert. I like Abdel-Haleem, and I like what I’ve read of the SQ’s translation. I think some will find difficult its Old English prose, but I didnt find anything particularly problematic based on what what I read. God Knows Best.

Adeeb

December 15, 2015 at 1:41 AM

Why don’t English speaking scholars form a commitee and produce an authentic English interpretation of Qur’an

ST

December 15, 2015 at 8:42 AM

Because this idealized group of scholars doesn’t exist. Every scholar has their own views and inclinations and their will never be agreement. And even if a few did somehow get together, had the scholarly abilities and time to put into such an effort, some in our community would disagree with their views (ashari vs maturidi vs mutazili vs shia etc. Or their madhab) and therefore react similar to what has happened with the SQ.

My guess is that here the editors chose not to be partisan, but now even that is being criticized. They’ve openly stated the opinions they have provided and yet there is a small group bent on proving there is a hidden perennialist/pluralistic view peppered throughout that they are denying. And what is meant by these terms is also clear as mud in the current discourse.

M.Mahmud

February 3, 2016 at 2:53 PM

Not even close. Even Salafis think that Asharis/Maturidis, Sufis, Barelvis and Shias are within the fold of Islam with exceptions to an individual.

On the other hand. Perrenialism is outright blasphemy. To try and conflate kufr with bidah is absurd and yet that is what you are doing. The strong reaction on all corners is in fact , damped and no where near as severe as it should be.

I’m glad Muslims are waking up to the falsehood being propagated and insha Allah the believers will all see these falsehoods and falsifiers for what they are.

Ruhul Kuddus

November 18, 2017 at 2:20 AM

——because some Muslim scholars will most certainly find deadly imperfection in it and rule it absolutely useless. You have seen examples here. In this forum, I feel like I am enjoying Napoleon Dynamite, a group dominated by hysterically short-tempered, overly intelligent, and profoundly self-satisfied actors—-. That their knowledge on the matter is so complete, they refute with complete refutation and then body slam the try-out without a sliver of remorse—-. I came to investigate something but returned somewhat confused.

Aafia

December 15, 2015 at 2:16 AM

Assalamu Alaikum,

Really Liked the Review but I found “The Quran by Oxford Publication ” much easier to Understand .Review here: http://islamhashtag.com/the-quran-oxford-world-classics-review/

yusuf kiswit

December 15, 2015 at 1:23 PM

We owe tremendous gratitude to the SQ editors for this incredible piece of scholarship. Thank you from the bottom of my heart. The [REDACTED] have no idea what you all went through to produce this illustrious opus. It is a blessed work, and it is clearly blessed by Allah. When the Qur’an itself was first printed, there were narrow minded retrogrades who objected. May we all learn to appreciate each other, and respect our differences like adults.

Mobeen Vaid

December 19, 2015 at 12:00 PM

Please refrain from calling human beings kilab. Alhamdulillah, this is a conversation among brothers and sisters. Keep that in mind.

M.Mahmud

February 3, 2016 at 2:55 PM

This is a conversation between people who are propagated kufr, speaking with bad adab and then screaming “bad adab” whenever their lies are ripped to shreds.

That’s everything in a nutshell. Alhamdulilah Muslims are waking up. Allah misguides and guides whoever He wills.

Luqman Bakr Mustafa

December 15, 2015 at 5:04 PM

First of all it is of paramount importance for you guys to have an idea about the three major lines or currents of thoughts namely Fundamentalists who are variably,in different circumstances,called Salafists,Reformists who intend to revisit the whole tradition under the influence of the massive political,socio-cultural and economic changes wrought by Modern philosophy and science,this is to say reformation is seeking to modernize religion,Traditionalists who are variably called Perennialists who hold that there is one single absolute truth which lies relatively at the heart of all religions.That is to say,there is a “Primordial Tradion” which has subsisted an will subsist. This is kind of belief in the esoteric unicity of Truth based on the nuanced distinction between Form and Substance implying that different religions are different manifestations in the relative realm of the Absolute. In other word,religions are various forms of Substantial Truth.Religions are different languages to express one truth,pure and simple.

Caner Dagli

December 15, 2015 at 6:09 PM

I wanted to share Prof. Mohammed Fadel’s comments on this review https://www.facebook.com/mohammad.fadel.39/posts/10153187736722031

A long and generally positive review of #StudyQuran. On the criticisms regarding the punishment of stoning for adultery, and the issue of salvation of non-Muslims, I think the criticisms are fair to the extent that the text fails to present the historically dominant views. I will have to read these provisions in the future to reach a judgment. But, revisionism on such questions should not be viewed as strictly verboten. Shaykh Muhammad Abu Zahra, for example, came to the conclusion that the punishment of stoning was a vestige of Mosaic law that should not have survived into Islamic law. Likewise, Mustafa al-Zarqa expressed the view that the punishment of stoning should be viewed as a ta’zir (a discretionary punishment) and not a punishment prescribed by revealed law. Neither Abu Zahra nor al-Zarqa can be dismissed as panderers to liberal sentiments. As for salvific pluralism, this article of mine, http://shanfaraa.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Volume.OUP_.Fadel_.FinalProofs.pdf, discusses how far 20th century Muslim theologians have moved from medieval jurists in stipulating formal embrace of Islam as a condition for salvation. True, they do this largely from the perspective of a capacious understanding of excuse, but when combined with pre-modern theological discussions of the requirement of sincerity on the part of all, it is not too far a leap to believe that non-Muslims who have not embraced Islam during their lifetimes out of good faith mistake or the like, will nevertheless be rewarded by God for the good they do in this life and are eligible for divine grace in the next. In short, I would suggest that the ironclad consensus that the reviewer alleges the editors of The Study Quran have violated on these two points is not as ironclad as the reviewers suggests, at least beginning in the 20th century, with dissenters not being limited to “liberals,” but also well-trained, and influential and prominent theologians and jurists from al-Azhar who have earned a deserved reputation for scholarly integrity, even if one may disagree with some of their positions.

Mobeen Vaid

December 15, 2015 at 9:01 PM

Jazak Allah khayr Dr. Dagli for sharing Dr. Fadel’s comments. Dr. Fadel is someone I have an immense amount of respect for and am humbled that he read the review. Nonetheless, I do want to respond briefly to his comments concerning the review: With respect to the first point, it is precisely the initial statement that is being taken to task in the review – the ‘historically dominant position’ was an agreed upon position among the four madhahib, the Ja’fari madhab (I’m admittedly not an expert here so will concede if wrong), the ahl al-hadith, and every major scholar to date prior to the 20th century. My reading of Q 24.2 in the SQ certainly did not reflect that reality. Had the SQ made mention of modern revisionist approaches as a handmaiden to the historically dominant view, then the critique would not have been included in the review.

As for the second point, the statement “it is not too far a leap to believe that non-Muslims who have not embraced Islam during their lifetimes out of good faith mistake or the like, will nevertheless be rewarded by God for the good they do in this life and are eligible for divine grace in the next,” is not a claim that I have engaged within this review. The primary points raised in the section concerning pluralism were: i) the SQ’s treatment of Dyophysite Christology as commensurate with tawhid and not constituting shirk ii) the SQ’s mentioning that the kitabi traditions have not been altered or subject to excessive distortions iii) the SQ’s situating of Q 2.62 as the rule beneath which all other verses reproaching the ahl al-kitab are subsumed, and iv) the distinction between the general ‘islam’ and proper Muhammadan ‘Islam’.

To be very candid, I do not believe there is any conceptualization of a Trinity in which God serves as a partner alongside a son and holy ghost as part of a godhead to accord with tawhid. I find the Quranic claims concerning tahrif/textual corruption something that should come naturally with even a casual study of Biblical preservation. Incongruities between source texts (OT Masoretic Texts vs Septuagint), input and modifications by early scribes, recurring recensions, and related issues are widely recognized and acknowledged. Ehrman’s ‘The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture’ is a good text that deals with the influence of Christological debates on the text of the Bible.

Finally, I am unaware of any scholar that viewed belief in the Prophet (pbuh) or the Quran as optional to ones salvation. The notion of ‘excused’ individuals accepts as a foundational premise the idea that those ‘excused’ individuals got it wrong on the question of theology. The effort of those scholars was to wrestle with how individuals who got that theological question wrong may, in fact, be saved within the workings of what the tradition had to offer. This is why, even in its most restrictive form, scholars refrained from casting definitive salvific claims on individuals. The standard position was one of suspending judgment (tawaqquf) with respect to individuals, while maintaining Islam as the only salvifically efficacious faith as a general matter.

God Knows Best.

Caner Dagli

December 15, 2015 at 9:51 PM

It is very difficult to offer a comments in great detail without writing an entire article but I would like to register a few thoughts. I don’t agree with casting the objections to rajm as “modern revisionist”; I find deeply distressing the idea that the Prophet is considered “optional” by us, which I will allow as being merely a poor choice of words with an unintended potential to mislead and raise unfortunate implications; and the view of the traditional school on the Trinity is not wholly accepting and neither is the SQ (read Schuon’s Logic and Transcendence for example, or my Muslim Response to Christian prayer). Again, these are just points to register, which is not meant to take away from the considerable, careful, and fair minded work you have done here. No doubt we will be writing about such matters at length in the future insha Allah– at least I intend to.

Mobeen Vaid

December 15, 2015 at 10:17 PM

Asalamualaykum Dr. Dagli,

The use of “modern revisionist” was in keeping with Dr. Fadel’s own characterizing of Abu Zahra and al-Zarqa’s proposed interpretations as “revisionism”. Given that al-Zarqa died in 1999 and Abu Zahra died in 1974, I think it is fair to classify them both as relatively modern authorities. I would be curious to hear more about your thoughts concerning the role of the Prophet (pbuh) within the conceptualization of salvation registered in the SQ. My own reading of the SQ was that “islam” as a general manner was required, and that the specific Muhammadan Islam was not a necessary requirement for entry to Paradise. In that vein, the belief in the Prophet (pbuh) may be considered as good, essential for embodying the characteristics of the best of mankind, etc. but not altogether necessary for salvation. I am not stating this to somehow impugn on the character of any of the authors (or their personal devotion to following the sunnah), but rather to articulate the content of the SQ and its logical conclusions.

Inshallah I am looking forward to any literature yourself or other SQ authors produce on the topic of the Trinity/Salvation and will certainly take up your suggestion and read your Muslim Response to Christian prayer. Best,

Mobeen

DI

December 16, 2015 at 12:26 PM

Mobeen, Thank you for pointing out all this.

I hope you are aware Professor Mohammed Fadel endorsed the publication of SQ so his comments are not neutral.

di.

Mobeen Vaid

December 16, 2015 at 3:31 PM

Salam DI,

I disagree. My own experiences have been that Dr. Fadel and many others who have endorsed the SQ are not, by virtue of endorsement, supporting every last view or opinion in the SQ. They are merely acknowledging the many benefits of the text which I have tried to outline in the review. Jazak Allah khayr

Mamdouh Mahmoud

February 6, 2016 at 2:31 PM

Dr. Dagli, I am surprised you mention sh. Abu Zahra! Do you know of his stand on translating the Quran?

Also, I am sure you are aware of the reaction of all his contemporaries regarding his Fatwa concerning Rajm. Sh. Qaradawi , who witnessed the shaikh’s announcement, recorded the incident and the scholars response .They all counted it as wrong Ijtihad and شذوذ on the Shaikh’s part, may Allah have mercy on him, from the consensus, old and contemporary.

Sh. Zarqa agreed with Abu Zahra with some technical difference defining الاحصان.

Sh. Abu zahrah is a respected jurist and usuli but made few wrong ijtihadat according to the rules of usool applied by qualified scholars as I am sure you are aware. He didn’t have a single credible daleel of the abrogation. In the usool: لابد ان يكون النسخ بدليل متراخ عن الدليل الاول ثابتا كثبوته. Also the mutawatir cannot be abrogated with any other than mutawatir. That is why the Shaikh didn’t announce it -as he said- for twenty years. Had he known his opinion carries weight, he wouldn’t hide it and as you know what hiding benefetial credible knowledge means. The new school of revising fiqh started only in the last century or two. Same two centuries you refrained from accommodating in your commentaries to a great extent!

I feel that there is a constant endeavor to entertain any opinion regardless of its weight and strength to endorse the editorial board’s view on certain issues. Hope I am wrong but I see it clearly manifested throughout the SQ commentary.

Naveed Mughal

February 13, 2016 at 11:03 PM

Please supply references when you mention that jurists from Al Azar have stated that salvation has paths other than belief in Allah, His Prophet and The Quran

elijah

December 16, 2015 at 5:40 PM

It is my belief that this review is very fair and thorough, though convoluted with Christological minutiae. I also found the reviewer’s sections on Departure from Consensus sequestering interpretive authority, and the Points of Caution unnecessarily worrisome.

It is true that the authors are researchers and not seminarians. Therefore, their choice verbiage “the Quran says” reflects the vigilance with which they approach a necessarily interpretable text to avoid the presumption of speaking for God. This is a technique to distance the interpreter from potential doctrinarian assertions, and I believe it is a mistake to review it as a “secular” academic approach (a rather meaningless designation).

It is indeed aptly entitled The Study Quran appropriate for students of the Quran, be they matriculated or unaffiliated. It is not however an Apologist Quran for imitative adherence to institutionalized convention. I believe such commentaries are very important and beneficial, and already quite numerous and the SQ is attempting to fill the void of intellectually engaging translations. “Normative Orthodoxy” as the reviewer describes, is a social-construct that is both negotiated necessarily and established circumstantially through power, not truth or hermeneutical “correctness”. Invoking the absence of intellectual precedence from the tradition to criticize some of the SQ claims is itself antithetical to Sunni scholasticism and scholarly dialectics. “Consensus” is itself not a proof, nor does it even relevant to the field of Tafsir.

What the authors intended, per their introductory statements, is to raise the level of Quranic literacy, an impossible feat for all communities, including Arabophones inept at interpreting Divine Speech revealed in 7th century Arabic. Not without its faults, I welcome this opportunity for students of the Qur’an to once again engage in a discourse with previous communities. However, I would caution the readers of this review to not deceive themselves into thinking that 1) that discourse has been unremitting and uninterrupted since before the 18th century collapse of Islamic intellectual institutions, and 2) a conservative and dogmatic interpretation of the Qur’an will contribute to Quranic literacy of the Muslim reader.

Mobeen Vaid

December 16, 2015 at 7:39 PM

Asalamualaykum Elijah,

The Christological minutiae may seem abstruse, but for a confessional traditionalist the notion that a conceptualization of God which includes a son can accord with the tawhid is, to put it mildly, non-canonical and an important consideration. Those placed in a position of responsibility to advise about the SQ will likely find its distinctions between Chalcedonian Christology and Monophysite Christology difficult to interpret, and the intent of the review was to not only expose them to that distinction, but to assert the orthodox conception of God’s unicity within that context.

As for the remainder of your comment, I believe we are speaking to two different audiences and will not find consensus. This review has been published on MuslimMatters, an overtly confessional Sunni website, and the review reflects my sensibilities as an admittedly confessional Muslim who is, thankfully, unencumbered by potential doctrinarian assertions.

With regards to your comments concerning orthodoxy, etc. – and I say this with the utmost respect – statements such as, ““Normative Orthodoxy” as the reviewer describes, is a social-construct that is both negotiated necessarily and established circumstantially through power, not truth or hermeneutical “correctness””, cannot come from someone who is embedded within the pedagogy of traditional Islamic studies. One who has had the fortune of sitting at the feet of scholars, learning from their ‘ilm and adab, cannot conclude that the normative tradition, matters of ijma’, and beliefs known of the religion by necessity, are simply established circumstantially through “power”. I don’t even know how to respond to the claim that “consensus is itself not a proof”, and the compartmentalizing of my treatment of consensus to tafsir is a complete misreading of the critique – one aspect of the critique pertained to ‘aqidah, and the other to fiqh, both fields in which consensus is not only a proof, but the *ultimate* truth in asserting epistemically conclusive rulings. That they appear in a work of tafsir is irrelevant to their designations as juridical and theological concerns.

That said, I don’t disagree concerning the value of the SQ and hope that my review was not read solely through the lens of its critiques as I did my best to highlight its many strengths. I hold the authors of the SQ in very high regard and my own interactions with them has only increased my regard for them. Jazak Allah khayr for your comment,

Mobeen

elijah

December 17, 2015 at 1:17 AM

Alaykum salaam Mobeen. Wherever you decide to begin, you will inevitably discover that not only is consensus of scholarly opinions a dogma of circularity, but that it holds no value today as an epistemic proof: it begins and ends with the community of Medina, per the formulators of Ijma’ as a source of law, as you are aware. Though many prestigious scholars arrogated the role of consensus as a privilege reserved for the scholarly elite, Imam Shaf’i’s explicit rejection of a scholarly class ruling over the majority as unprincipled is in fact the more traditional opinion in accordance with the prophetic guidance of the Messenger of God. A more analytical and less triumphalist view of consensus today: it is now a relic of invaluable, if not mythologized past, as is the intellectual authority of an obsolete class of ecclesiastics. Inshallah we can meet for a meaningful conversation engendering our mutual respect.

Wassalaam

Mohamed Abdallah

December 17, 2015 at 1:52 PM

Assalamu ‘alaikum Elijah,

I think you are confusing two things here: there’s “consensus” (of the juridic kind you’re talking about), and then there’s Consensus on the macro scale (which is a horse of a different color). The question about the place of juristic consensus in deriving laws centers(ed) precisely around issues like whether the relevant consensus was just of the scholars or the whole community, how to ascertain a scholarly consensus (i.e., do you need explicit agreement from every living known scholar or just absence of objection over a long period of time), etc. Scholars did and do differ over these issues, and it is true that often a “consensus” (ijma’) is claimed on an issue, but that this is only meant in a looser, approximative sense.

This type of consensus — i.e., on specialized issues among the specialists of a particular field of knowledge (like fiqh or ‘aqida) — is entirely different from those fundamental issues of belief (‘aqida) and/or practice (fiqh) that are so universally attested to by the entire umma — both scholars and non-scholars — in all times and places without exception as to constitute “ma’lum min al-din bi-l-darura,” i.e., that which is “known OF NECESSITY to constitute a part of the religion.” Every Muslim, for example, has always attested — on the ‘aqida side — that there is only one God, that Muhammad (saas) was a true messenger, that no further messengers will be sent after him, that there will be resurrection after death, etc. Similarly, on the fiqh side, every Muslim has always known and attested that there are five obligatory daily prayers in Islam, that fasting in the month of Ramadan is compulsory, that wine, gambling, zina, and eating pork (among other things) are prohibited, etc.

These are all textbook examples of ma’lum min al-din bi-l-darura, and if there is anything which we can say we know about the deen with absolute certainty (and yes, I mean that as an epistemological claim to yaqin), it is these things. Denying any of them has usually been considered sufficient to nullify one’s very Islam (though mitigating circumstances may apply, such as widespread ignorance of the religion or the complex articulation of heretical positions which raise honest doubts in some people’s minds about what are otherwise completely clear darura issues). When Imam al-Shafi’i questioned the narrower, strictly scholarly consensus that you mentioned as epistemically unable to yield certainty (yaqin), it was only to contrast it with this other category of things that are so obvious and well attested to simply be KNOWN (by everyone) to be a part of the religion. Al-Shafi’i never rejected this category or the absolutely binding and epistemically certain nature of those beliefs and practices which it includes. Quite to the contrary: this was the “test case,” so to speak, against which he was comparing the status of the more narrowly defined consensus of the scholars.

From an epistemological point of view, capital-“C” Consensus of the “ma’lum min al-din bi-l-darura” sort is, in a sense, the gold standard. Note that no one doubts the obligatory nature of five daily prayers, while these are nowhere mentioned explicitly in the Qur’an. Their obligatoriness is not the product of (“mere”) scholarly consensus because it was never derived through a process of scholarly deduction (or ijtihad). The kind of consensus Shafi’i had in mind was when an issue was the result of ijtihad and all scholars did ijtihad and came to the same conclusion. Issues of “ma’lum min al-din bi-l-darura” are not inferential to begin with; they are “pre-ijtihad,” so to speak. They are the very raw material of the deen, the data points, the facts (please excuse my use of materialistic metaphors and terminology here; I mean no disrespect). And it is not possible that the umma all together be in fundamental error on a basic point of ‘aqida or fiqh that falls under “ma’lum min al-din bi-l-darura.” Not only is there the hadith that “Never will my umma agree upon an error,” but it simply makes no theological (or epistemological) sense to hold that Allah would have sent a message through a messenger and that EVERY SINGLE PERSON that the messenger taught and to whom he transmitted the message, as well as all generations after them (both of scholars and non-scholars), “miraculously” concurred on an exactly identical, but MISTAKEN, view of a given issue, especially one as foundational as what is being discussed here. And there is no dogmatism in that, but just plain common sense.

No known or recognized figure in Islamic history (prior to Rene Guenon in the 20th century and his subsequent followers) has ever held that previous dispensations, even assuming they had not been corrupted, continue to be concurrently valid with God’s final dispensation to mankind after the coming of His final messenger, or that a person, having come to know about this final messenger and been fairly apprised of the message he brought and the proofs that authenticate it, may continue following a religion other than this final dispensation (i.e., Islam, or “historical Islam,” if you insist) and still be saved. As Mobeen pointed out above, the fairly wide view of “excused” persons (due to the message not reaching them or reaching them only in a distorted form) does not mean that their religions remain valid, nor does it authorize Muslims to go around identifying which forms of previous dispensations are “orthodox” (and therefore continue to be salvific) or not.