#Current Affairs

A Remarkable Life Unbowed: Jamil “Rap Brown” Amin

Imam Jamil “Rap Brown” Al-Amin’s passing sparks a powerful reflection on his legacy as a civil rights leader, Black Muslim visionary, and political prisoner whose life shaped generations.

Published

By

Ibrahim Moiz

By Ibrahim Moiz

Tributes And A Legacy of Defiance

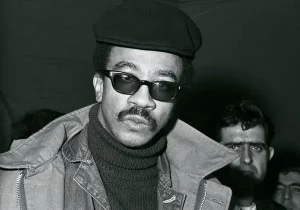

The death in a high-security prison of veteran civil rights activist and community imam Jamil “Rap Brown” Amin has brought forth a tide of grief and tributes from throughout the United States and beyond. A pioneering and influential figure in the 1960s civil rights movement, imam Jamil’s life ended in a quarter-century of imprisonment under hotly contested charges and repeated refusals of appeal that could not staunch his influence as a groundbreaking activist and community leader within and beyond the Muslim and black communities.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Tributes have poured in for an aged activist long seen within his communities as a political prisoner falsely accused of crime and vindictively imprisoned despite a terminal illness. “Unsurprisingly,” remarked activist Zoharah Simmons, “the carceral system was unwilling to show any mercy for Brother Jamil…refusing a compassionate release! They made sure he would spend his last days under federal lock and key. But the State didn’t have the last word. Brother Jamil was bloody but unbowed.”

Outrage, Love, and Community Grief

Kalonji Changa mourned the imam, who “was not only my spiritual leader, he was one of my movement leaders, so I take his death personal. They allowed him to go blind and suffer the ravages of cancer while denying him the basic, life-saving medical care owed to any human being, let alone a political prisoner!”

The imam Omar Suleiman wrote, “For years we fought to free him. Today he is free. From prison to paradise God willing. He never lost his dignity, his voice never shook. His innocence was proven, but the system didn’t care. We cared. We loved. And InshaAllah, we will continue to move forward with his legacy.”

Who was this community leader that has attracted such fierce loyalty and affectionate solidarity? We will proceed to recount the remarkable life of Jamil Hubert Abdullah Amin Brown, who played a notable but largely overlooked role in the history of the United States, its civil rights and minority rights, decolonial struggle, and Western Islam.

Rap Brown

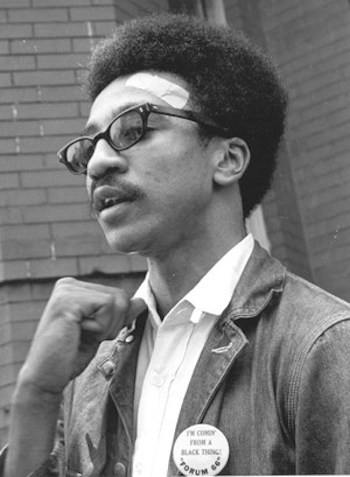

Nicknamed “Rap Brown” for the razor-sharp wit that he frequently used to cutting effect in firestarting condemnations of the American status quo, Jamil Abdullah Amin was born as Hubert Gerold Brown at Baton Rouge in 1943, growing up in Louisiana during the “Jim Crow” heyday. He and his elder brother Ed Brown were involved in activism for the rights of the widely downtrodden black community, reading widely and plunging into student politics.

Brown joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which began sit-ins and protests against racial segregation and discrimination in southern universities. In summer 1963 he witnessed its protests at the Maryland town Cambridge, led by Gloria Richardson, and was convinced that black activists needed to retain the right to fight back against violent intimidation.

Under Surveillance and Pressure

Though Richardson reached an accord to end Cambridge’s official discrimination with attorney-general Robert Kennedy, the brother of American president John Kennedy, civil-rights activism would repeatedly find itself in the cross-hairs of both racial prejudices as well as Cold War paranoia.

This drew a correspondingly sharp response from activists such as Brown; though he had been involved in legal civil-rights actions, such as the registration of black voters, he increasingly reserved the right to respond to violent provocation. Activists such as Brown, Malcolm Little, and Stokely Carmichael were also influenced by the decolonization of Africa and coordinated with liberation movements in African, Muslim, and decolonized, often leftist, countries, whose struggle they saw as linked to their own: in a reflection of this influence, the trio would change their names to, respectively, Jamil Abdullah Amin, Malik Shabazz “X”, and Kwame Ture.

Cold War and Confinement

After Malcolm’s murder, Ture, who led the Nonviolent Committee with Jamil as a major lieutenant, set up the Black Panthers movement, whose grassroots organization and “shadow governmental” structure immediately attracted subversion by Hoover’s agency. Jamil, who succeeded Ture as leader of the Nonviolent Committee, changed its name to “Student National Coordinating Committee” because, he quipped, “violence is as American as cherry pie.”

Indeed, the 1960s were a violent period, with assassinations claiming the lives of not only Malcolm but the Kennedy brothers and King. In this context and against significant intimidation, Jamil saw little need to adopt nonviolence as an inflexible principle. “Black folks built America, and if America don’t come around, we’re going to burn America down.”

This attracted caricatures of firebrand trouble-making; in fact, Jamil proved a thoughtful, disciplined organizer who would nonetheless hold his ground under fire with an often blisteringly sharp tongue. Though open to negotiations, he refused terms set by what he saw as a plainly unjust status quo.

In spring 1965 he joined a delegation that met Kennedy’s successor in the presidency, Lyndon Johnson, and was alarmed at the level of deference shown in what was effectively a negotiation. When Johnson complained that the activists’ nightly demonstrations had disturbed his children’s sleep, Jamil gave his condolences for the inconvenience but added that “Black people in the South had been unable to sleep in peace and security for a hundred years.”

Escalation, Resistance, and the Road to Arrest

Johnson did introduce civil-rights protections, but only at the cost of a militaristic foreign policy whose cauldron was the Vietnam war. For Jamil, who linked the struggle for civil rights to international solidarity against colonial supremacism, this was an unacceptable compromise.

In typically cutting parlance he called Johnson the“the greatest outlaw going” for his militarism abroad: “He fights an illegal war with our brothers and our sons. He sends them to fight against other colored people who are also fighting for their freedom.” This matched the views of the Black Panthers, who attempted to merge organizations and promoted Jamil to their honorary “justice minister”.

Jamil’s call, influenced by decolonial struggles abroad, for urban insurgency against oppression put him on thin ice, and the security establishment soon swooped. In summer 1967 he revisited Cambridge, which had dishonored its end of the 1963 agreement; he was promptly arrested in hotly disputed circumstances for supposedly inciting a riot; police chief Brice Kinnamon claimed to have staunched a “well-planned communist attempt to overthrow the government”, and governor Spiro Agnew alienated most black voters with his insistence that Jamil had been responsible. The case attracted widespread attention and was interrupted when the courthouse was bombed; Jamil went underground for eighteen months before he was sentenced to a five-year imprisonment.

Revolution by the Book

During his five-year imprisonment, Jamil converted to Islam. When he emerged, still only in his mid-thirties, and moved to Atlanta he led a life that belied the propaganda that had depicted him as a reckless troublemaker. In fact, he focused on quiet community building, beginning at the mosque and spreading out through the community, both Muslims and otherwise.

In one of his last interviews, delivered from prison, he quoted the Muslim caliph Umar Farouq ibn Khattab’s statement that Islam depended on community, which depended on leadership, which depended on allegiance and commitment to the roles and guidelines outlined by Allah. Thus a community, the incarcerated and ailing imam took pains to emphasize, depended on commitment to the path set by the Creator.

Jamil lived by his words, and set by personal example a thriving community of black Muslims grew in west Atlanta; Masood Abdul-Haqq, who moved there in autumn 1992, saw “the West End Muslim scene [unfold] like some sort of Black Muslim Utopia. A soulful adhan was the soundtrack to Black children of all ages in kufis and khimars playing with each other on either side of the street. The intersecting streets near the masjid gave way to a large covered basketball court, on which the game in progress had come to a halt due to the number of players who chose to answer the melodic call to prayer.

Overlooking this scene from the bench in front of his convenience store, like a shepherd admiring his flock, was a denim overall and crocheted kufi-clad Imam Jamil. Before I heard him utter a single word, it was obvious to me that I was in the presence of a transcendent leader.”

Building a Model Community and a Revolutionary Ethic

Khalil Abdur-Rashid, who grew up in the same community, noted that Jamil “would retain his devotion to changing the prevailing system and worked to teach his community to cultivate an alternative way of living that is not indicative of token social justice programs. He taught the importance of the five pillars of Islam and revolutionary ‘technologies of the self’ that, when actualized at the communal level, transform the society into a better one.”

Remarkably in a period where neoliberal economics and a burgeoning drug epidemic had ravaged much of the urban United States, the imam took pains to combat such social evils, which he linked to spiritual and material impoverishment. Man was not, he would emphasize, an animal consigned to give in to its appetites, and to surrender to such social evils was both personal and communal harm.

Though privately regretting certain “unseemly” language in earlier work, Jamil never compromised on his belief in communal liberation and emphasized the role of spiritual and personal development in his later writings, tying together personal and political progress for the community in his Revolution by the Book.

He visited these themes again at the funeral of his longstanding comrade Kwame Ture, and influenced his elder brother and longstanding influence Ed to embrace Islam as well. Though he maintained a low profile, he played a major role in leading what was by all accounts a dynamic and profound society; Atlanta mayor John Johnson gave the imam with an honorary police badge as a token of appreciation for his social work.

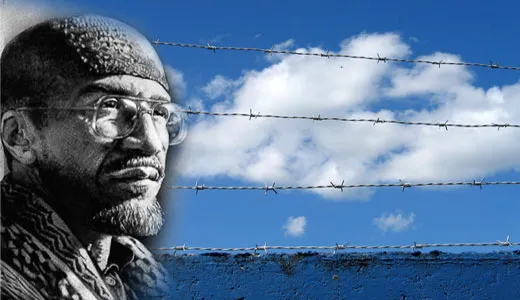

Confinement in the age of “War on Terror”

Yet with the end of the Cold War and the replacement of communism as a major irritant with “radical Islam”, Jamil once more found himself in the crosshairs of state paranoia. As a well-known Muslim who had collided with the state a quarter-century earlier, he was sporadically questioned whenever an incident of “Muslim terrorism” came up during the 1990s. In spring 1999 he was pulled up for allegedly imprisoning a policeman, simply because he had kept the badge given him by the mayor.

The following spring, two policemen tried to bring him in, did not find him at home, and after leaving were shot, one fatally. The survivor accused Jamil, even though his description of the suspect was wildly different and another individual later confessed. In any case, the accusation was enough to bring Jamil into custody. Capitalizing in large part on the anti-Islamic paranoia that took hold after 2001, the prosecution managed to convict him in spring 2002 and he was put in a high-security prison.

We need not recount at length the story of Jamil’s trial beyond the curiosity that key pieces of evidence were pointedly ignored, as was the confession of another man, and that the authorities, eventually as high as the Supreme Court, refused appeals and even clemency in light of the elderly prisoner’s failing health. The case bore similarities with his imprisonment in the late 1960s: contrived charges that ran rougshod over contrary evidence, coupled with paranoia relating to the alleged threat of the day: communism in the 1960s, “radical Islam” now.

A Passing That Echoes Through History

It is small wonder that supporters considered Jamil a political prisoner deliberately left to perish in a high-security confinement absurd for a sick, dying old man. Changa, who had been introduced to both Islam and revolutionary activism by the imam, was unequivocal: “This was a cold, calculated, STATE-SPONSORED EXECUTION designed in the high offices of the colonial apparatus!” He referred to it as “the assassination of an aging prisoner, carried out not with a noose, but with a waiting list and a bureaucratic denial slip!”, and “the refinement of the colonial terror—using the prison hospital as the final torture chamber for those deemed too dangerous to live in freedom, and too old to survive neglect!”

But he ended on a calmer note: “Imam Jamil al-Amin was a prisoner of conscience until his very last breath. Now, by the mercy of Allah, he is truly free of their chains…Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji’un. To Allah we belong, and to Him we shall return.”

Editors note: MuslimMatters offers our condolences to the Amin family and those who loved Imam Jamil Al-Amin, to his followers in the Dar movement. We learn from his life and commitment to Al Haq. We encourage people to attend his Janazah bi Gha’ib that is being held in several locations.

Related:

Book Review of Revolution by the Book by Imam Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin (Formerly known As H Rap Brown)

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Ibrahim Moiz is a student of international relations and history. He received his undergraduate degree at the University of Toronto where he also conducted research on conflict in Afghanistan and Pakistan. He has written for both academia and media on politics and political actors in the Muslim world.

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

[Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy

Op-Ed: Bitterness Prolonged – A Short History Of The Somaliland Dispute

Far Away [Part 6] – Dragon Surveys His Domain

Green March In The Sands Of The Blue Sultan: Morocco And The Conflict Over The Western Sahara

An Iqbalian Critique Of Muslim Politics Of Power: What Allamah Muhammad Iqbal’s Writings Teach Us About Political Change

Darul Qasim College Given License To Grant Master’s Degrees

Muslim Book Awards 2025: Finalists

The Muslim Book Awards 2025 Winners

Op-Ed: From Pakistan To Gaza – Why Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan Terrifies Power And Zionism

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

[Dhul Hijjah Series] Calling Upon the Divine: The Art of Du’a (Part 1)

IOK Ramadan 2025: Four Steps | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Do Your Best | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Giving Preference to Others | Sh Zaid Khan

Trending

-

#Islam1 month ago

Restoring Balance In An Individualized Society: The Islamic Perspective on Parent-Child Relationships

-

#Life1 month ago

Faith and Algorithms: From an Ethical Framework for Islamic AI to Practical Application

-

#Current Affairs1 month ago

Quebec Introduces Bill To Ban Prayer Rooms On College Campuses

-

#Current Affairs4 weeks ago

An Iqbalian Critique Of Muslim Politics Of Power: What Allamah Muhammad Iqbal’s Writings Teach Us About Political Change

GregAbdul

November 28, 2025 at 4:59 PM

Thank you for remembering this Great Emam.

Munawar Hussain

November 29, 2025 at 2:01 PM

Imam Jamil’s life is a powerful reminder of how faith, dignity, and community leadership can transform generations. His unwavering commitment to justice and spiritual discipline continues to inspire many of us who strive to stay connected to our deen while navigating the challenges of modern life.

For those reflecting on his legacy and looking to stay consistent with their daily prayers and spiritual routine, there are great resources available that provide accurate global prayer timings and help with better spiritual organization. Tools like these offer small but meaningful support in maintaining discipline—something Imam Jamil’s life exemplified so deeply.

May Allah grant him the highest ranks and allow his legacy to guide us toward stronger communities and steadfast faith. Ameen.