featured

The Role Of Kurds In The Dissemination Of Islamic Knowledge In The Malay Archipelago

Published

“O abode of the Kurds, blessed is your dwelling place, where the moons of knowledge shine

I was pleased with what you have become, a garden with flowers of investigation, in which classes are flourishing

For us, there are scholars in you; when I mention them, my heart is scorched, and my emotions overflow.

Masters who illuminated our knowledge with their insights, as they clarified what the ages had dispersed

Their schools have become beacons of knowledge, with a gaze fixed on the highest of places

They sacrificed their souls to preserve that by which the Shariah of the chosen Prophet speaks

Connoisseurs who have traversed the depths of study, with their understanding surpassing the overflowing seas

They preserved the knowledge of Shafi‘i, like suns that shine brightly in the eye and the heart.”-Uthman b. Sind al-Wa’ili (d. 1826)

(Kurds being historically located in the landlocked Upper Mesopotamia and the Zagros mountains, and the seafaring Melayu people occupying the Malay Archipelago) One may ask, what connects Kurdistan and the Nusantara? Kurds were once a frontier Muslim people too, living on the periphery of the Muslim heartlands. After all, the first mosque in Anatolia was built by the Kurdish Shaddadid Emirate after the battle of Malazgird in 1071. Similarly, in the Kurdish lands, there was very little armed resistance to the Rashidun armies as well, as attested to by early historian al-Baladhuri “the lands of Jazirah were one of the smoothest conquests.” Jacobite Christians (a plurality among Kurds) even helped the Caliphate fight against the Byzantines.

However, my aim with this article is to present the history of the spread of Islam in the Malay Archipelago through the lens of the Kurdish teachers. Kurdish scholars (Mullas) dominated the teaching positions in Mecca and Medina during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries of the common era which were destinations of pilgrimage, and eventually the de-facto Muftis of the entire Hijaz region. Islam’s arrival in the Malay Archipelago, which includes parts of modern-day Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, and the Philippines, is a fascinating historical process marked by trade, cultural exchange, and gradual conversion over several centuries. Islam began to spread to the Malay Archipelago through trade routes established by Arab and Indian merchants.

From Trading Routes to Sultanates

By the 7th century, traders from the Arabian Peninsula and the Indian subcontinent were active in Southeast Asia, bringing with them Islamic ideas and practices. In addition, Muslim traders from Gujarat and the Coromandel Coast established trading posts and settlements in the region. The influence of Indian Muslim scholars and the Sufi faqirs further facilitated the spread of Islam. The spread of Islam was–like elsewhere- gradual, with local rulers and influential figures converting to Islam acting as catalysts. One milestone was the Sultanate of Malacca, founded in the early 15th century, played a crucial role in the spread of Islam. The sultan, Parameswara, converted to Islam and became known as Sultan Iskandar Shah. Islamic sultanates and kingdoms began to form, and they became centers of Islamic learning and culture. Sultanates like those in Aceh, Johor, and Sulu promoted Islam through their influence and control over trade routes. The arrival of European colonial powers, such as the Portuguese, Dutch, and British, also influenced the spread of Islam. While colonial powers often sought to control and convert regions to Christianity, they also had to contend with established Muslim societies. In that decisive era, our story comes in.

Kurdish Scholars and Indonesian Scholarship

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

After the initial introduction of Islam, Indonesians played a significant role in its further spread by traveling to Mecca and other holy cities to seek spiritual knowledge and deepen their understanding of the faith. Despite the long distance and challenging journey, many Indonesians undertook the Hajj and often spent several years in the Hijaz for study. In the seventeenth century, a period for which we have considerable information, Indonesian Islam was heavily influenced by Indian traditions. The most prominent mystical order at the time was the Indian Shattariyyah, and a key mystical text was a short work by the Indian author Burhanpuri. Other religious texts studied in the region were also popular in India.

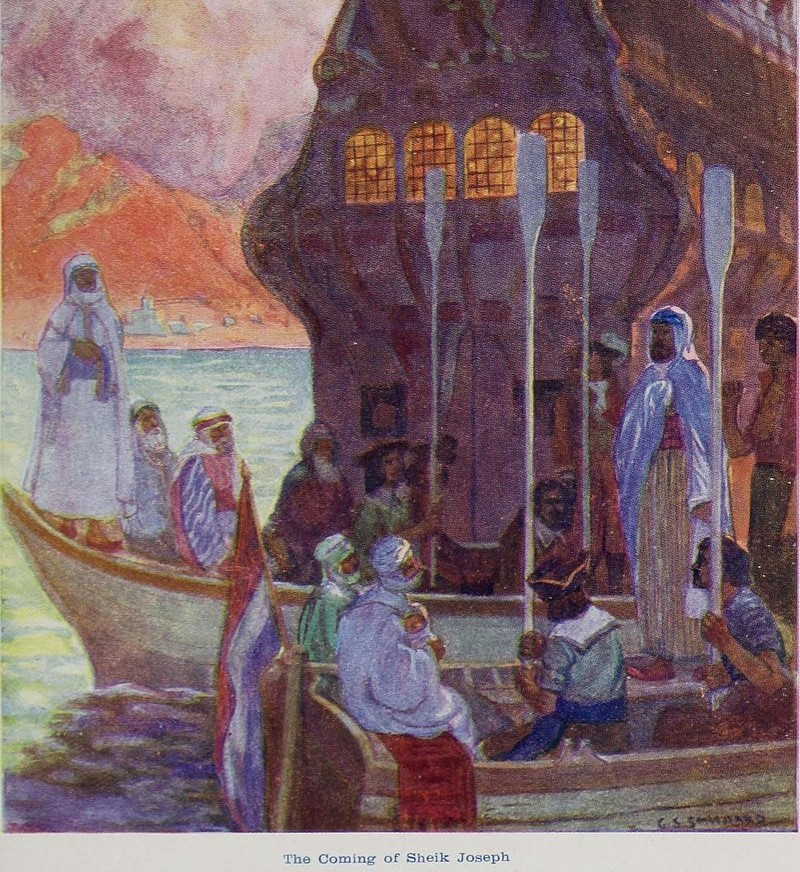

G.S. Smithard; J.S. Skelton (1909) – The Coming of Sheik Joseph

However, according to the scholar Martin Van Bruinessen, this Indian influence did not come directly from the subcontinent but through Medina and Mecca. Teachers in Medina introduced the Shattariyya to the first Indonesians, with Ibrahim al-Kurani (d. 1690), an elite Kurdish scholar, being particularly influential. Kurdish scholars were often sought after by Southeast Asian students in Arabia, partly due to the shared Shafi`i legal tradition, but also due to a deeper spiritual affinity. This connection was most evident in the areas of mysticism and devout practice, where Indonesian and Kurdish Islam found their closest similarities.

Two great Indonesian scholars were apprentices of al-Kurani (Gorani), the famous ‘Abd al-Rauf al-Fansuri al-Sinkili (d. 1695) and Yusuf al-Maqassari (d. 1699), taking the ijazat of the tariqahs Shattariyyah and Khalwatiyyah from him. ‘Abd al-Rauf was one of the first major saints of Islam on the archipelago and had great influence in the spread of Islam in Aceh. Sheikh Yusuf of Java was destined to become a preacher of Islam in the Cape of Good Hope after his exile due to his participation in the war against the Dutch. Al-Kurani probably had more students from the archipelago considering the dozens of epistles and fatwas he wrote in response to the emerging issues of the people of Jawa (then referring to the whole archipelago).

Afterwards, the Mufti of Medina was to be another Kurd, Muhammad b. ‘Abd ar-Rasul al-Barzanji (d. 1694), the ancestor of all the Barzanjis of Arabia and India. His great-grandson Ja‘far b. Hasan (d. 1764) authored ‘Iqd al-Jawahir, a prose remembrance of the life and times of the Prophet (peace be upon Him) that would be known in the East and the West of the Islamic world as “the Barzanji” Mawlid, a household name on the archipelago. His biography of Sheikh ‘Abd al-Qadir al-Gilani, similarly, became popular in Indonesia. The Barzanji family retained Muftiship of Medina for 64 years, but the Barzanji teachers continued to have Indonesian students well into the 20th century.

Our next Kurdish teacher is the namesake of many Indonesians who –to this day- have “Kurdi” as their first name. Yes, a portion of the pious Indonesian population have and continue to name their children after scholars and authors of popular books in the Islamic sciences. Muhammad b. Sulayman al-Kurdi (d. 1780) is the main Mufti of the Haramayn and a high authority in the Shafi‘i school of jurisprudence. He is the author of Hawashi al-Madaniyyah, a supercommentary on Ibn Hajar’s sharh Muqaddimah al-Hadhramiyyah, which is held in high regard by the Indonesian scholars, but he was also the teacher of a number of disciples from the archipelago, namely the Borneo-native Muhammad Arshad al-Banjari, the author of the most important Malay fiqh work, Sabil al-Muhtadin, who was greatly impacted by the Sheikh’s charisma. Khalidi records that oral tradition has it that ‘Abd al-Samad al-Falimbani as well as two less well-known scholars, ‘Abd al-Wahhab Bugis and ‘Abd ar-Rahman Masri from Jakarta join Muhammad Arshad in attending al-Kurdi’s lectures in Medina, and return to Indonesia together in the 1770s when the al-Kurdi sends them there to instruct their compatriots.

Coming back to the more spiritual teachers, we get the world-renowned Mawlana Khalid al-Kurdi (d. 1827), while he himself was not known to have disciples from the archipelago. Although he got the Naqshabandi Taqriqah from Abdullah Dehlawi and popularized it back home, his student Abdullah al-Arzinjani had multiple Indonesian disciples, chief of whom was Isma‘il Minankabawi who spread his teaching among his people. Arzinjani founded a Zawiyyah on Mount Abu Qubays in Mecca which became a hub of students from the archipelago and at one point had dedicated Malay-speaking instructors. Another Khalidi-Naqshabandi master was Muhammad Amin al-Kurdi (d. 1914) of Erbil, a murid of the Sheikhs of Biyarah, he wrote what’s according to Van Bruinessen the most widely read Naqshabandi manual called Tanwir al-Qulub.

The Islamic Richness of the Current Malay Archipelago

One reason for the prominence of Kurdish teachers among Indonesian Muslims could be the shared adherence to the Shafi‘i madhhab, which Indonesians have followed since at least the 16th century, similar to the Kurds. This contrasts with most other Arabs, Turks, and Indians, who follow different schools of thought. To this day, Indonesians studying in the Middle East often find it easier to connect with Kurds because of this commonality in religious practice. Another aspect is the historical proficiency of Kurdish scholars in both Fiqh and Sufism which were strongly sought by those students. Geopolitical factors have positioned the Kurds as intermediaries among three major Islamic cultural traditions: Persian, Arabic, and Ottoman Turkish. Located at the crossroads of these regions, Kurdistan partly separates and connects these cultural centers. For centuries, Kurdish intellectuals have been proficient in their own languages as well as Persian (the literary language of India till the 19th c.), Arabic, and Turkish. This multilingual capability has enabled them to serve as bridges between these diverse cultures. Many Kurdish scholars studied in one part of the Muslim world and later taught in another. This openness to adventure was what pushed Ahmad b. Ismail al-Kurani (d.1488) to travel to the east and west ,and finally find himself in Ottoman lands. It was his mastery that earned him the Sultan’s confidence, to the extent that he gave him carte blanche to rectify his wayward son Mehmed –future conqueror of Constantinople- and prepare him for the Sultanate; and rectify he did, reportedly even beating up the future Sultan for persisting in his folly.

This connection shows how the Islamic world is deeply interconnected and how –in this case- Kurdish scholars helped bridge gaps between different cultures and regions. Their contributions highlight the rich history of Islamic scholarship and cultural exchange, and also discredits the thesis that Islam was spread by the sword, and similar tropes. Those scholars connected Islam (practice), Iman (faith), and Ihsan (spiritual cultivation), thereby forming a harmony between the mind, the soul, and the body in their teaching.

Related:

– Perpetual Outsiders: Accounts Of The History Of Islam In The Indian Subcontinent

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

A young student of medicine in Kurdistan region of Iraq with an old part-time interest in History, Fiqh, Tassawuf, biology and linguistics. I aspire to shed light on our forgotten past and tradition, sharing seldom mentioned facts and giving context to pivotal events in our history.

When Love Hurts: What You Need to Know About Toxic Relationships | Night 11 with the Qur’an

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Someone | Night 10 with the Qur’an

Fifteen Years in the Shadows: The Strategic Brilliance of the Hijrah to Abyssinia

Ramadan As A Sanctuary For The Lonely Heart

Cultivating A Lifelong Habit Of Dua In Children

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

[Podcast] Guardians of the Tradition: Muslim Women & Islamic Education | Anse Tamara Gray

Who Am I Really? What Surat Al-‘Asr Teaches Muslim Teens About Identity | Night 1 with the Qur’an

Ramadan In The Quiet Moments: The Spiritual Power Of What We Don’t Do

Where Does Your Dollar Go? – How We Can Avoid Another Beydoun Controversy

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Someone | Night 10 with the Qur’an

When to Walk Away from Toxic Friends | Night 9 with the Qur’an

What Islam Actually Says About NonMuslim Friends | Night 8 with the Qur’an

Week 1 in Review: Is Your Teen Actually Changing? | Night 7 with the Qur’an

Why Your Teen Wants to Change Their Muslim Name | Night 6 with the Qur’an

MuslimMatters NewsLetter in Your Inbox

Sign up below to get started

Trending

-

#Islam2 weeks ago

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

-

#Current Affairs1 month ago

[Podcast] Should Muslims Ally with Conservatives or Progressives? | Imam Dawud Walid

-

#Life1 month ago

[Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy

-

#Islam1 month ago

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

Shoaib

October 15, 2024 at 9:20 PM

Thank you for this very informative article. I was not aware of the close links between the Kurdish and Indonesian ulama.

hey

October 29, 2024 at 6:07 PM

.