#Culture

Islam In Nigeria [Part I]: A History

Published

The history of Islam in Nigeria is not well-known to many Muslims outside of the country, or the continent. Many people know Nigeria as the most populous African country, but fewer realize that with a population of about 200 million, even the more conservative 2018 estimate that 53.5% of Nigeria’s population is Muslim, makes it the country with the largest Muslim population in Africa, and the fifth largest Muslim community in the world – after Indonesia, Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh.

For socio-political purposes (and those of this article) Nigeria is considered along the major geographical demarcations of the rivers Niger and Benue – as divided into the North, Southwest, and Southeast regions. While the country has hundreds of tribes speaking over 500 language dialects, each of these regions has a majority ethnic group: the Hausa-Fulani, the Yoruba, and the Igbo people respectively.

History of Islam in Nigeria

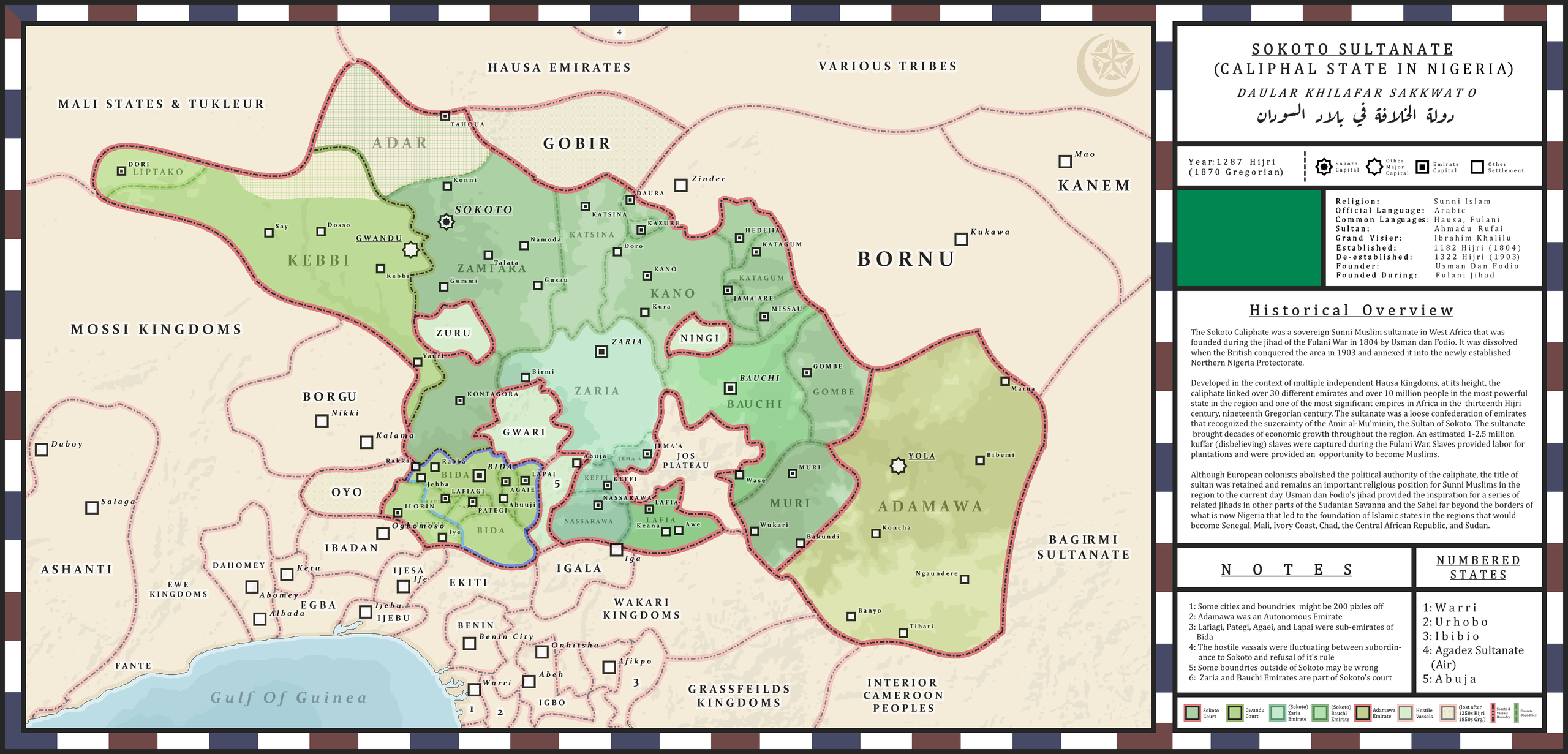

Islam has existed within the northeast regions of the country – now known as Nigeria since the 11th century (1085 – 1097) as a result of trade between the Kanem empire of Borno and Northern African regions. Some have argued that Islam had reached Sub-Sahara Africa, including Nigeria, as early as the first century of the Hijrah calendar, through Muslim traders during the reign of Uqba ibn al Nafi (622–683 AD). The religion penetrated Hausaland in the fourteenth century and by the 16th century, was moving into the countryside and towards the Middle Belt. In 1803, Usman dan Fodio founded the Sokoto Caliphate which became one of the largest empires in Africa – stretching from modern-day Burkina Faso to Cameroon, and including most of northern Nigeria and southern Niger. At its height, the Sokoto state included over 30 different emirates under its political structure, and ruled through much of the 19th century, until its dissolution by British and German forces on 29 July 1903. The relevance of the caliphate and its emirates (and their sacking by colonial forces) to Islamic education was far-reaching.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

In southwestern Nigeria, Yorubas came in contact with Islam in the 14th century during the reign of Mansa Kankan Musa of the Mali Empire (1312 – 1337) through the travel of traders from the region. This explains the traditional Yoruba name for the religion – esin imale, the religion of the people of Mali. The first Mosque in Yorubaland was built in Ọyọ-Ile in 1550 AD to cater to these foreigners, but large-scale conversion to Islam of indigenous people only began in the 18th-19th centuries, from a mass migration of people into the Ọyọ kingdom. Many of these immigrants were Muslims who introduced Islam to their hosts. After Ọyọ was destroyed, Muslims from there (Yoruba and immigrants alike) relocated to newly formed towns and villages and became protagonists for Islam.

The advent of Islam into the southeast region was relatively late. Oral records put the first Muslim in Nsukka as a horse trader from the Middle Belt who naturalized into the community (1909 – 1918). Other foreigners who shared his faith joined him in his new home, gradually building up a modest community of Muslims. Notably, this was before the incursion of the colonialists into Igboland, but there is no record of the conversion of an indigenous Igbo person to Islam until 1937. This region continues to have only a minority Muslim population to date.

Historical Significance of Islamic Studies in Ancient Nigeria

The spread of Islam heralded the advent of a literary education in the region, which had previously maintained a rich legacy of oral transmission of knowledge. Prior to that, the history of a people, especially in terms of their mythology and significant events, as well as their poetry, proverbs, and collective values, were passed down from generation to generation via oral narration. The historians, poets – especially the elderly among them, and among the Yorubas especially, who had an entire system of talking drums – the drummers, and musicians were seen as the custodians of knowledge.

With the emphasis of Islam on knowledge, and its adherents’ well-developed systems of education – both religious and secular -, Muslims of this region were soon introduced to reading, writing, and the studying of the Qur’an and various branches of Islamic sciences. In addition to religious edicts to seek knowledge, acquiring Islamic education became another source of prestige; initially the prerogative of the elites, but became increasingly common as the need for teachers grew, especially after the Sokoto jihad.

In addition, Muslim West Africa was tied to the Islamic networks stretching across North Africa and the Mediterranean to the Middle East. This, and an important trans-Saharan network enabled and necessitated Arabic literacy as the lingua franca of trade in the region. It was therefore considered prestigious to study Arabic and the Islamic sciences. This continued to provide the groundwork for religious scholarship, facilitating the exchange of ideas between West African Muslims as far as Mali, and to Sudan and beyond, forming the basis for classical Islamic education.

Traditional Methods and Curriculum of Studying Islam in Nigeria

Before colonization, the most common educational path of Muslim children in Nigeria was Qur’anic education taught by teachers called Mallams in the north or Alfas in the southwest; usually a graduate of a similar school. These teachers were versed in Arabic to varying degrees and were influenced by the knowledge and traditions passed down from medieval Timbuktu and from other West African Islamic texts. Students converge in the compound of the mallam’s house or at a Qur’anic (sometimes, a boarding) school where they recite the Qur’an and learn Islamic teachings.

Nigerian Muslim girls at their Islamic Studies school [PC: Legit.ng]

The next stage, usually consisting of pupils with ages ranging from 5 to 14 years, is when the pupils are introduced to Arabic alphabets; the consonants and vowels, and how to string them together to read what has been written. Once that is mastered, the teacher will start writing on their wooden board, the slate (allo), short verse, and surah for them to learn and commit to memory. As the pupils progress in this stage, they are gradually introduced to the art of writing, to develop writing skills, under the guidance of the teacher or other senior students. When the art of writing is perfected, the pupil is allowed to read directly from pages of the Qur’an, listening to the teacher to assimilate some of the rules of Tajweed unconsciously, until he completes the recitation of all the surahs of the Qur’an at least once. Further instructions on Islamic rituals are given including the rites of ablution, tayammum, prayer, and other rituals, although more specialized aspects (e.g. fiqh) will be learned at a later stage. This was commonly the stage where the child – old enough to enter an economic occupation (male) or marriage (female) – stopped attending the studies.

For students proceeding further, usually with the expectations of becoming Islamic education teachers and clerics themselves – and often from specific families – the student thereafter begins to learn the meaning of the chapters, their exegesis (tafseer), and the sciences of recitation (tajweed). He, or more rarely she, may also begin learning the rules of Arabic grammar and studying texts of scholars written in Arabic (and Hausa or Fulfide in the north). Students who were considered exemplary or who wanted to specialize could thereafter travel to the major centers of learning Islamic knowledge that existed within their region – Ibadan, Ilorin, Sokoto, and Maiduguri being renowned for scholarly pursuits – or as far as Mali and Sudan.

Prior to the British colonization, children stayed at home with their parents, especially for the elementary stages, attending schools in their immediate environment. In the north, under the Caliphate, inspectors were introduced to report the affairs of the school to the emir of the province and the schools were funded by the state treasury, the community, parents, from sadaqah and zakah controlled by local emirs, and sometimes the farm output of the students.

Colonization

White men’s incursion into the entity known as Nigeria was into two phases. The Portuguese, who reached Lagos as early as 1472 – and Benin in about 1477 -, were primarily concerned with trade, and conceived that Africans had to be civilized to be good customers. To be civilized, to them, was to be Christianized and have some form of Western education. However, the obstacles outweighed the advantages, and the ‘civilization’ project was abandoned without significant differences in the educational and religious culture of the locals.

The second phase of colonization and the beginning of an everlasting impact began in September 1842 when the first British Christian mission landed at Badagry on the southwest coast. The missionaries became the custodians of education, which was used as a tool for mass conversion, aimed at producing a Christian population who could serve in the colonial administration. The Colonialists and Missionaries worked together to subdue the existing religions and to relegate the existing educational system, -particularly in the southwest -, into oblivion. For instance, the Yoruba language that was previously written in Arabic alphabets known as ajami was substituted with the Roman alphabet that is currently in use.

Children were compelled to attend church services and take baptismal names in order to attend the, usually mission, schools and were given white-collar jobs upon graduation. Although Muslims resisted long and hard, even denying their children the Western education en masse, the prudence of such action was eventually called to question when the educated Christian minority began gaining prominence over the affairs of the Muslim majority – a state of affairs that continues in the southwest till today.

In the north, the British deposed most emirs and defunded the educational system; usually called Almajiri system (from almuhajiroon). The remaining emirs lost control of their territories and, with no support from the community, emirs, and the government, the system collapsed. The British neither established secular schools on a large scale nor advanced existing institutions. Western education was conducted by Christian missionaries, making it available only to a small portion of Nigerians. And because Islamic scholars and graduates of the Islamic education system did not have a western education, they were disqualified from white-collar and political jobs.

The British did, however, establish large urban centers. Many Mallams migrated from rural areas to the cities in search of livelihoods, making northern cities, such as Kano, became important centers of Islamic learning. Parents started sending their children to the cities to study Islam, and as neither the teachers nor students had financial support, they turned to alms begging and menial jobs for survival. Because traditional Islamic teaching was considered a duty to God, the Mallams depended on charity or patrons to make ends meet, and students were expected to assist teachers in raising funds through door-to-door solicitations. This practice became the norm and is what is recognized as the almajiri system of today.

Immediate Post-Colonization Period (1960 – 1990s)

As a response to the discriminatory colonial practices and in the period preceding Nigeria’s independence, Muslim political leaders were cognizant of the need for Western-trained graduates to fill positions in government. In the south, they organized and founded Muslim schools with a western education focus, and nominally restructured the existing Islamic education system. While in the north, the response was to create integrated Muslim-led secular schools with the introduction of a formal School of Arabic Studies in Kano to train Qadis. In addition, Islamic studies were introduced into the primary and secondary school curriculum.

The rise in Muslim-styled Western education reduced the number of children attending Qur’anic schools, although most parents continued to send their children, in the evenings and weekends, to acquire the basics – learning to read the Qur’an in Arabic, usually in mosques or unstructured Islamiyyat. Because these Islamiyyat did not have the prestige of secular schools, had been relegated by the community to a less important and voluntary status, was taught by teachers who straddled the poverty line, and often used harsh methods to pass their messages across, they soon acquired a bad reputation and many children stopped or did not attend. This led to a generation of ‘educated’ Nigerian Muslims who did not study Islam, if at all, beyond knowing how to recite the text of the Qur’an.

[To be continued…]

Resources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islam_in_Nigeria

Uchendu, Egodi. (2010). Evidence for Islam in Southeast Nigeria. Social Science Journal – SOC SCI J. 47. 172-188. 10.1016/j.soscij.2009.09.003.

Ogunbado, Ahamad. (2012). Impacts of Colonialism on Religions: An Experience of Southwestern Nigeria.. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 5. 51-57. 10.9790/0837-0565157.

Related reading:

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Muti'ah is an Obstetrician-Gynecologist, homeschooling mother, writer and multiple-award winning author. Her books, mostly contemporary Islamic fiction, write to the Nigerian Muslim experience.

When Love Hurts: What You Need to Know About Toxic Relationships | Night 11 with the Qur’an

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Someone | Night 10 with the Qur’an

Fifteen Years in the Shadows: The Strategic Brilliance of the Hijrah to Abyssinia

Ramadan As A Sanctuary For The Lonely Heart

Cultivating A Lifelong Habit Of Dua In Children

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

[Podcast] Guardians of the Tradition: Muslim Women & Islamic Education | Anse Tamara Gray

Who Am I Really? What Surat Al-‘Asr Teaches Muslim Teens About Identity | Night 1 with the Qur’an

Ramadan In The Quiet Moments: The Spiritual Power Of What We Don’t Do

Starting Shaban, Train Yourself To Head Into Ramadan Without Malice

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Someone | Night 10 with the Qur’an

When to Walk Away from Toxic Friends | Night 9 with the Qur’an

What Islam Actually Says About NonMuslim Friends | Night 8 with the Qur’an

Week 1 in Review: Is Your Teen Actually Changing? | Night 7 with the Qur’an

Why Your Teen Wants to Change Their Muslim Name | Night 6 with the Qur’an

MuslimMatters NewsLetter in Your Inbox

Sign up below to get started

Trending

-

#Islam2 weeks ago

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

-

#Current Affairs1 month ago

[Podcast] Should Muslims Ally with Conservatives or Progressives? | Imam Dawud Walid

-

#Life1 month ago

[Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy

-

#Islam1 month ago

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

Spirituality

February 10, 2023 at 12:38 PM

Jazak Allahu Khayran for writing this article!

I’m struck between the similarities between the rise and fall of Islamic education in Nigeria as compared to India. Did this happen all over the colonized world?

Sad state of affairs.

Looking forward to future installments!

Bashir Abubakar

February 10, 2023 at 3:00 PM

Brilliant! I hope the continuation will feed my curiosity on the role of Islam in slavery and how it handled Nigerian multiculturalism as some tribes have been claiming to be the owners of the religion in Nigeria.

Joyce Larsen

February 11, 2023 at 11:49 PM

Salaam aliakum,

My husband is from Nigeria and my children this claim this heritage to a degree. I am desperate for all history resources to put things in perspective and enjoyed this article very much. Thank you so much for recognizing all the scholarship of West Africa!

Mehmood

February 27, 2023 at 5:40 AM

This article was a fantastic read, and I loved how it was presented. Thanks for sharing!