Aqeedah and Fiqh

Yasir Qadhi | The Definition of “Travel” (safar) According to Islamic Law | Part 2

Published

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

Continued from Part 1

1.5 The Distance in Modern Measurements

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

So what exactly does a ‘day’s journey’ mean? Not surprisingly, there is no easy method of converting classical measurements into modern ones. It appears that many researchers (classical and modern) did not pay due attention to scientifically converting such measurements into modern ones. What follows is my brief attempt to illustrate the hurdles that one faces.

The standard units of measurement for travel during early Islam were thefarsakh and the barīd. However, the Prophetic traditions use the term ‘day’s travel’. So the first issue at hand is to convert the Prophetic ‘day’s travel’ into the classical terms of farsakh andbarīd. Before we even begin that, let us first define these terms and establish a relationship between them.

A barīd was a distance that a messenger could travel before he needed to stop to allow his animal to rest. If the message was urgent, then at the end of every barīd there would be a fresh animal waitingfor him. Eventually, the term began to be applied to the ‘messenger’ himself and then to the actual ‘message’, hence modern Arabs still call the postal service ‘barīd’.[1]

A farsakh appears to be a Persian measurement that the Arabs adopted (it was also adopted by the British and called a ‘league’). Most early works mention that four farsakhsmake up one barīd.[2] So it can be said that each barīd is divided into four smaller units of afarsakh (plural is farāsikh).

1 barīd = 4 farāsikh

So far, so good. Now the real confusion begins.

The first real issue is: How many barīds can be traversed in a 24-hour period? Unfortunately, this is not something that is unanimously agreed upon, and it is this difference of conversion that results in one difference of opinion over the number of days required to consider someone a ‘traveler’.

Collectively, the Ḥanbalīs, Shāfʿīs and Mālikīs all agreed that the distance of ‘travel’ wasfour barīds. However, they disagreed amongst themselves as to what exactly this meant in terms of ‘days of travel’. Some within these schools said that in any 24-hour period, a maximum of two barīds could be traversed; other scholars within these same schools, however, said that four barīds could be traversed in one 24-hour period. It is because of this conversion difference that these three schools of law had opinions of both one-day and two-days as being the minimal amount of ‘travel’.

One day’s travel = EITHER two barīds OR four barīds [both opinions held]

What is important for us to note is that these three schools were in agreement with the limit as being ‘four barīds’.

Therefore, for the ‘three schools’,

Sharʿī distance of travel = 4 barīds = 16 farāsikh [For the ‘3 schools’]

This is the opinion of the schools of law other than the Ḥanafī school. As for the Ḥanafīs, they also disagreed regarding how many farsakhs can be traversed in a day [and there is significant disagreement amongst their own scholars as well].

In order to simplify matters, the majority opinion within the Ḥanafī school appears to be that five farāsikh can be traveled in a 24-hour period [note that some Ḥanafī scholars said six, some said seven].[3]

Thus, for this school:

Sharʿī distance of travel = 3-day journey = 3 days x 5 farāsikh/day = 15 farāsikh [Ḥanafī school]

Ironically, even though the Ḥanafīs have a larger quantity in terms of travel days, because the actual journey traveled per day is shorter, the net difference was not of great significance.

Therefore, in the end, all four schools of law are relatively close to one another in terms offarāsikh (16 or 15).

The second dilemma that we face is: How exactly does one translate a farsakh into the modern measurements of miles and kilometers? Obviously, depending on one’s estimate of a farsakh, the distance of a day’s journey will vary accordingly.

Here is where we encounter our first serious problem.

We begin by pointing out that many medieval texts define a farsakh as being ‘3 mīls’. Mīl is, of course, how the Arabs pronounce the word ‘mile’. This would be absolutely perfect, until we understand that this mīl is not the equivalent of the modern ‘mile’! It appears that the Arabs got this word (as did the Romance languages) from the Roman mīllia, which they (i.e., the Romans) measured as a thousand paces by foot. A ‘pace’ was defined to be a full stride of a Roman soldier (in our understanding, that would be two steps, one with each foot). It has been estimated that this ‘Roman mile’ was actually around five-thousand feet (in our current understanding of ‘feet’). It was only centuries later that the English Parliament standardized the exact length of miles and feet, and decreed that 1 mile = 5280 feet (around 1.6 km). [Why and how they came up with number is really beyond the scope of this article – our readers are already confused by now, and those who are interested may look this tidbit up in any encyclopedia].

While the Arabs took the name from the Romans, they did not take the same measurement. It is also claimed that the Roman soldier’s step was considerably larger than the average step of other ethnicities, especially those who had shorter statures.

The Roman mīllia was adopted by many different cultures. Therefore, to distinguish this Arab version of the mile from other adopted versions, it was called the ‘Hashemite mile’. Other versions of the mile were the Russian, the Danish, the Portuguese, and the German (not to mention the Nautical Mile, which is different from land equivalents).

Our scholars did attempt to define this Hashemite mile (a.k.a. a mīl); however, in the days before scientific measurements and international treaties that governed such matters, they could not come up with a unified definition. Some classical texts mention that a mīl consists of twelve-thousand steps; others claimed that a mīl was as far as the eye can see; yet others claimed that it was the distance where one could recognize a figure of a human in the distance but could not tell whether it was a male or female.[4]

What is clear from all of this is that not only is a mīl undefined, even if one of these definitions were to be taken, it would not be scientifically precise. The bottom line is that the Arab mīl, a.k.a. ‘Hashemite mile’, had never been scientifically defined. How could it, in an era before the Newtonian scientific revolution that we are all familiar with and upon whose standards we conduct experiments?

In the 16th century, the British parliament offered a precise definition that has stuck to this day: that 1 mile = 5280 feet (around 1.6 km). Remember that this conversion factor was a relatively recent one, offered by the British. However, when some of our modern scholars attempted to then translate these ancient distances of farāsikh and barīd into modern units, they appeared to have read in the British conversion units into the ancient terms. Hence, they simply ‘chugged and plugged’ away, using the ancient definition of one farsakh being three medieval Hashemite mīls, and every ‘mile’ (sic.) being 5280 feet. Thus, they moved from an ancient term (farsakh) to a medieval one (mīl) to a British definition of another (mile).

This was not the only attempt to translate the farsakh into a recognizable unit. The famous scholar Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr (d. 463 AH) stated that a farsakh is roughly 10,500 ‘arm-lengths’ (dhirāʾ).[5] Very well, but what does that mean for us in our units of measurement? An average arm-length has been estimated in our times to be around 48 centimeters (i.e., 0.48 meters).[6] It appears that a large group of later scholars accepted Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr’s conversion factor and based modern calculations on it.

Other scholars, such as al-Nawawī, al-Ramlī, and al-Ḥajjāwī all held the position that afarsakh is in fact eighteen-thousand dhirāʾ.[7]

Hence, plugging and chugging away:

– With the conversion factor of one farsakh = 3 mīl = 3 ‘standard’ miles

Four barīds = 16 farsakhs x 3 mīl/farsakh = 48 mīl = 48 miles = 77.25 km

– With the conversion factor of Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr:

Four barīds = 16 farsakhs x 10,500 dhirāʾ/farsakh x 0.48 meters/dhirāʾ = 80.64 km (50.4 miles)

– With the conversion factor of al-Nawawī:

Four barīds = 16 farsakhs x 18,000 dhirāʾ/ farsakh x 0.48 meters/dhirāʾ = 138.24 km (86.4 miles)

For reasons that I could not understand, the modern Ḥanafi position typically calculates a distance of 15 farsakhs to be 77 km (or 48 miles).

It can be seen that the conversion factor of al-Nawawī actually yields almost double the distance of the first conversion factor. It can also be seen that all of these conversions are rather tenuous; none of them could have been known or measured with such precision during the time of the first generations of Islam.

Now that we have successfully (?) translated these ancient units into three possible distances (and note that there are even more possibilities if we were to discuss other conversion factors), let us return to the issue of the distance required for one to be considered a ‘traveler’.

1.6 The strongest opinion

Now that we have discussed the actual distance of these measurements, let us return to the original question: which of these opinions appears to be correct?

The strongest opinion – and Allah knows best – appears to be the last one (viz., that a traveler is one who customarily understands his situation to be one of ‘travel’), for a number of reasons:

1) Ibn Taymiyya’s point that the Prophet did not specify any distance is a very poignant one. He neither ordered that the earth be measured, nor did most of the travelers of the time calculate the distance that they traveled. It does not make sense, therefore, that the Shariah would place a numerical value when such unit-definitions were not known or followed by the majority of that generation.

2) Even in the hadiths that the majority use (about a woman traveling without a maḥram), there are discrepancies between ‘one-day’, ‘two-days’ and ‘three-days’ – all three wordings are reported in one or both of the Saḥīḥ works. So which one should be resorted to?

Additionally, all three hadiths use the word ‘travel’; would it not, therefore, be safe to assume that the Prophet was not trying to link the word ‘travel’ to any distance, but rather simply discussing the issue of a woman traveling without a maḥram? Furthermore, the tradition about permitting wiping over the socks has nothing to do with setting a limit for ‘traveling’ – it merely sets a time-limit for allowing someone to wipe over one’s socks.

Therefore, there is nothing in the hadith literature that one can safely use as a defining distance for travel.

3) As can be clearly seen, there is no precise and agreed upon conversion factor for translating a ‘day’s journey’ into a tangible and precise measure. There are a number of ‘grey areas’ in this calculation. What exactly is a ‘day’s journey’? How many barīds are in such a journey? How many farsakhs can be traveled in a day? How long is a farsakh? What exactly is a mīl? And so forth.

If this is the case, it does not make sense that our Shariah would have obligated us to measure ‘travel’ in units that to this day remain undefined and ambiguous.

4) To place a precise measurement on ‘travel’ seems to contravene the purpose of the law and hence the maqāṣid of the Shariah. The purpose of this ruling is to ease the burden upon the traveler by allowing him to shorten and join the prayer. If a traveler is engrossed in figuring out how far he has traveled (imagine in the days before car odometers gave this information), it is as if the Shariah is placing a bigger burden on him by asking him to calculate a distance that he is, in all likelihood, not capable of doing.

5) This distance really makes very little sense in modern times. A distance of 80 km is more akin to a picnic than to a travel – and according to Ibn Taymiyya’s definition, if one were to go to a park outside of one’s city with the express intention of returning in a short period of time, this would not constitute travel. If we look at the frame of mind of a family who is going on a day-trip to a park outside the city versus going on a journey, there is a significant difference. When one goes on a day-trip, the house is left as is, the neighbors are not told, life ‘at home’ is not assumed to be interrupted, and so forth. On the other hand, when one goes on a ‘travel’, miscellaneous factors must be taken care of before embarking on a ‘journey’. All of this is known to and experienced by the people of our time.

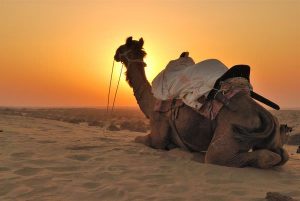

6) Before even beginning to ‘convert’ such ancient units into modern ones, an even more profound dilemma can and should be discussed. For those who follow one of the ‘standard’ opinions, the issue must be raised: is it not too literalistic to measure a ‘day’s- journey’ by the means and methods of eras gone by? In other words, if the primary means of travel of the time were horses and camels, and based on that one extrapolates a day’s journey, would it be permissible (in fact, would it not be more in line with the goals of the Shariah) to measure a modern day’s journey in car-travel time?

Personally, if I were to follow this opinion (meaning, if I were to follow a ‘two-day journey’ opinion), it would make more rational sense to me to measure a ‘day’s journey’ in the standard travel-means of our times, namely: a car. This then raises a further question: Does this mean we can eventually extrapolate to a passenger plane? How about a private jet? Questions abound; answers, on the other hand, are not so easy to bring forth.

All of this lends further credence to the position of Ibn Taymiyya: that a ‘traveler’ is one who is customarily considered one. An average Muslim does not need to resort to a scholar, or to a map, in order to find out if s/he is a traveler or not: you know it by what you do to prepare for a trip and your psychological frame of mind.

To be continued…

In our next and final installment, we will discuss how long one remains a traveler at a non-resident location.

[1] There are other opinion on the origin of this word as well. See Lisān al-ʿArab, 3/86-8.

[2] ‘Most’ because there is also an opinion that two farsakhs make up a barīd.

[3] Al-Tahānawī, Iʾlāʿ al-Sunan 7/282; al-ʿAynī, Sharḥ al-Hidāya 3/4.

[4] Lisān al-ʿArab, 11/639, al-Shawkānī, Nayl al-Awṭār, 3/245.

[5] To be more precise, he claimed that each farsakh was three ‘miles’, and each ‘mile’ was three-thousand five-hundred arm-lengths; hence each farsakh would be 3 X 3,500 = 10,500 arm-lengths.

[6] Najm al-Din al-Kurdi, al-Maqadir al-Sharʿiyya, p. 258.

[7] To be more pedantic, they claimed that a mīl is six-thousand ‘arm-lengths’, and a farsakhis three mīls, hence a farsakh would be 18 thousand arm-length. See: al-Ḥajjāwī, al-Iqnāʾ, 1/274; al-Shawkānī, Nayl al-Awṭār, 3/245.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Sh. Dr. Yasir Qadhi is someone that believes that one's life should be judged by more than just academic degrees and scholastic accomplishments. Friends and foe alike acknowledge that one of his main weaknesses is ice-cream, which he seems to enjoy with a rather sinister passion. The highlight of his day is twirling his little girl (a.k.a. "my little princess") round and round in the air and watching her squeal with joy. A few tid-bits from his mundane life: Sh. Yasir has a Bachelors in Hadith and a Masters in Theology from Islamic University of Madinah, and a PhD in Islamic Studies from Yale University. He is an instructor and Dean of Academic Affairs at AlMaghrib, and the Resident Scholar of the Memphis Islamic Center.

Faith, Identity, And Resistance Among Black Muslim Students

Moonshot [Part 12] – November Evans

From The Prophets To Karbala: The Timeless Lessons Of Ashura For Muslims Today

Moonshot [Part 11] – The Fig Factory

Nationalism And Its Kurdish Discontents [Part II of II]: Kurds And Turkiye After Ottoman Rule

Moonshot [Part 11] – The Fig Factory

Moonshot [Part 12] – November Evans

Moonshot [Part 10] – The Marco Polo

Moonshot [Part 9] – A Religion For Real Life

Moonshot [Part 8] – The Namer’s House

[Dhul Hijjah Series] Calling Upon the Divine: The Art of Du’a (Part 1)

IOK Ramadan 2025: Four Steps | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Do Your Best | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Giving Preference to Others | Sh Zaid Khan

Abu "i wish i had a kunya"

July 8, 2011 at 1:04 AM

MashAllah, enlightening article.

I wish Sheikh Yasir would write more articles related to islamic sciences (like this one) and less about politically charged issues.

We like the “old” sh. Yasir :)

Zeyad

July 8, 2011 at 10:24 AM

I agree! I love articles that blend Islam, sciences, and world history! More please!

Jazak Allah khair!

Amy

July 8, 2011 at 4:15 AM

Salaam

The first time I heard the opinion about travel being defined as what a persons considers travel to be made so much sense to me, while until then I had been baffled by seemingly arbitrary and obscure definitions. I think there is a flaw in the logic that a complex question (“What is travel?”) with many inherent variables (by what means, at what speed, through what terrain, etc) can be reduced to a single “magic number.” I’m not sure if it was your goal to demonstrate the futility of relying on archaic measures and conversion factors, but I think you succeeded.

And I think your answer–the position of Ibn Taymiyya–is the only one that can withstand the scrutiny of time, as should the religion of truth.

sakib

July 8, 2011 at 5:16 AM

Abu, what’s wrong with politically charged issues? Is politics not part of Islam?

Amad

July 9, 2011 at 5:35 PM

exactly. Those are the issues that affect us as much as religious issues. May Allah put barakah in Shaykh Yasir’s works in all affairs that he provides guidance on… politics and religion.

Umar

July 9, 2011 at 9:58 PM

Ameen.

Don’t you feel that his “religious” articles are a lot more comprehensive though? – as opposed to current affairs articles with a religious perspective.

Salam

Abu "i wish i had a kunya"

July 10, 2011 at 10:27 PM

Sorry bro wish I could answer but moderator not letting my posts go through. Thanks.

Leo Imanov

July 8, 2011 at 6:57 AM

bismi-lLaah wa-lhamdu li-lLaah wa-shshalatu wa-ssalamu ‘alaa rasuli-lLaah wa ‘alaa alihi wa man walah

assalaamu ‘alaikum wa rahmatu-lLaahi wa barakaatuH

masya Allaah what an article syaikh yasir qadhi has written, an enlightening one!

wa bi-lLaahi-ttaufiq wa-lhidayah

wa-ssalamu ‘alaikum

Zakir

July 8, 2011 at 12:49 PM

Interesting article but at the same time confusing. I found Islam to be very logical and practical.It make individuals accountable for their own actions depending on each persons ability.

Why cant we see travelling as a choice made by the person .If he or she has the means to pray during the journey pray and if not adopt the concessions offered by Allah with best intentions.

Most places now have facilities for prayer even while travelling and if we don’t have it we can even sit and pray.

I have been asking many scholars to guide me to understand this , this article sheds a good light but still confusing.Hope the author will give us final easy to understand and practical conclusion for all of us to follow in the next part.

Jzk

Shuaib Mansoori

July 9, 2011 at 6:59 AM

An insightful series indeed. JazakAllah Khair! May Allah place success in this year’s IlmSummit. Awaiting your reply to my last email :)

Teena

July 9, 2011 at 6:21 PM

Assalamu Alaikom! I found this article very beneficial alhamdulilah! This is something that I had been concerned about for a while now because I just got a new job in Clear Lake (though I live in Katy) and because I’ll be working on 12 hour shifts for three or four days a week, the only way that I can make this work is to stay in Clear Lake at a hotel for the three days in which I’m working back-to-back shifts. I would consider myself to be a traveler: I’ll pack baggage, stay at a hotel, eating outside (i.e. not being able to cook for myself), etc. It would definitely make things easier for me to be able to combine and shorten the prayers. Jazak Allahu Khair.

MangoLassi

July 10, 2011 at 12:48 PM

JazakAllahu khayran ya shaykh!

Couple of points: I grew up in the middle east and some of my dad’s colleague’s at work used to shorten their dhuhr and asr because they claimed that they lived in the suburbs and their commute distance was long! How absurd! I remember some of our family friends also shortenining and combining their prayers when they used to go to the mall in the evening cause they claimed it was far away and that the prophet (pbuh) did the same when he went shorter distances. You have shown that this interpretation is not sound cause going to work and going to the mall in the city does not constitute travelling :)

My question is that sometimes when we’re fling international and are about to leave for the airport, I usually shortern and combine dhuhr and asr EVEN though I’m at home but theoritically in “travel” mode cause my bags are packed and am ready to leave for the airport. Is this fine? Then I usually pray combine maghrib and isha in the plane. Or should I pray dhuhr and asr while at the airport?

talwar

July 11, 2011 at 12:51 AM

Two separate issues here:

Shortening salah is related to travelling.

Combining (jam’) is related to difficulty.

Since you are at the airport and within your city, do not shorten the salah. If you are going to face difficulty in doing your salah whilst travelling, then combine the relevant prayers at the airport.

Short answer, combine if you have to but don’t shorten at the airport, wallahu alam.

saalik

July 11, 2011 at 9:23 AM

“A distance of 80 km is more akin to a picnic than to a travel”

Interesting to note that a < 80km trip, albeit short, can be considered travelling to a specific individual. Even to those who follow Ibnu Taymiyyah's opinion. In fact, the real issue is what is 'customarily' considered travel. Because someone may claim driving 350+km's (a round-trip/day trip) is not travel. Whereas someone may see it as travel.

It boils down to that even those of us who agree with this opinion still need to understand what is customarily defined as travel because it differs among the people.

Lastly, the shaykh himself (Ibn Uthaymeen) gave some nice advice in following this opinion:

“The statement of Shaykh Ibn Taymiyyah is closer to what’s correct. Even when there’s a

difference in what people customarily consider traveling, there’s still no problem if the person acts

according to the specified distance opinion because some of the Imaams and scholars sincerely

striving towards a correct verdict have said it. So, there’s no problem, if Allaah wills. As long as

the issue is left undefined, then acting in accordance to what is normally considered travel is the

correct opinion.”

http://www.ibnothaimeen.com/all/books/article_18007.shtml

Mohammed Khan

July 11, 2011 at 12:48 PM

Considering that taking Ibn Taymiyyah’s opinion will make things extremely hard for everybody and will leave the masses utterly confused, I’ll just stick to the opinion of the Madhab I follow.

Jazakumullah for spending all the time to compile this though.

abdur rahman

October 5, 2013 at 8:14 AM

Actually, i was always confused about the travel issue, due to the famous sahaaba’s opinions and also the 4 madaahib.

Reading this article, personally, made me realize how easy ibn taymiyyah and scholars like him made islaam. So, you stick to following your madhab and me and quite a few others will stick to following something that is easy and halaal, at the same time.

Following a respected scholar’s opinion on an issue made confusing by the madaahib.

Ibn Aziza

February 16, 2014 at 6:34 AM

Following a Scholar is following a Madaahib…..If you could care to explain the difference please?

anonymous

July 11, 2011 at 4:28 PM

I wish more people would take Sh. Yasir’s (hafidullah) example and branch out and cover both. The Ummah is in need of leadership while also being in need of understanding the other classical issues of Islam.

Asma

July 12, 2011 at 11:05 PM

Assalamu ‘alaikum wa rahmtuallah,

JazakAllah khair for the clarification of this topic.

Question:

– How do define a journey? I mean if ibn Taymiyyah’s opinion were to be considered, how would the following situation be regarded: A person sleeping over at another person’s house, and thus brings forth with them luggage (e.g., change of clothes, toothbrush, etc). The distance between both houses would be no more than a half hour drive. (I guess you use your better judgment in such a case?)

p.s., you can’t bring up the topic of travelling without going into detail about the topic of travelling without a mahram for a female :P It would be ideal if you can also shed some light into the differences of opinion about that, considering the need for clarification and understanding in this day and age where travelling for women has almost become a necessity at times.

InchiroAunt

May 21, 2013 at 5:40 AM

As Salaamu Alaikum

An article on women traveling with/without mahrams would be immensely helpful. There are many sisters who revert to Islam and, obviously, do not have mahrams and if they are unmarried(willingly/unwillingly) how are they to manage traveling for employment, healthcare, caring for ill relatives, etc. Also, there are many sisters born and raised Muslim who may not have any male relatives or the Muslim male relatives they have are not practicing and are unable to fill the role of a mahram due to leaving Islam or not being of sound mind. I pray this will be your next article.

Pingback: Yasir Qadhi | The Definition of ‘Travel’ (safar) According to Islamic Law | Part 3 | MuslimMatters.org

Pingback: Yasir Qadhi | The Definition of ‘Travel’ (safar) According to Islamic Law | Part 1 | MuslimMatters.org

Pingback: MM Treasures | Yasir Qadhi | The Definition of “Travel” (safar) According to Islamic Law | Part 1 - MuslimMatters.org

ummAda

December 6, 2014 at 7:04 AM

Amazing article, masha Allah! There are so many opinions on the length of travel, but I had never heard of Ibn Taymiyyah’s. This article puts so many things in perspective. Jazak Allah khair for delving into these matters.

Jafar Saeed

October 13, 2015 at 12:23 PM

Hmmm. This is very good research, but I am slightly disturbed by the fact that the author seems to curtly dismiss the other opinions in a few paragraphs as if the Companions (ra) and tabieen who held these opinions didn’t know what they were talking about and hadn’t considered these arguments.