#Current Affairs

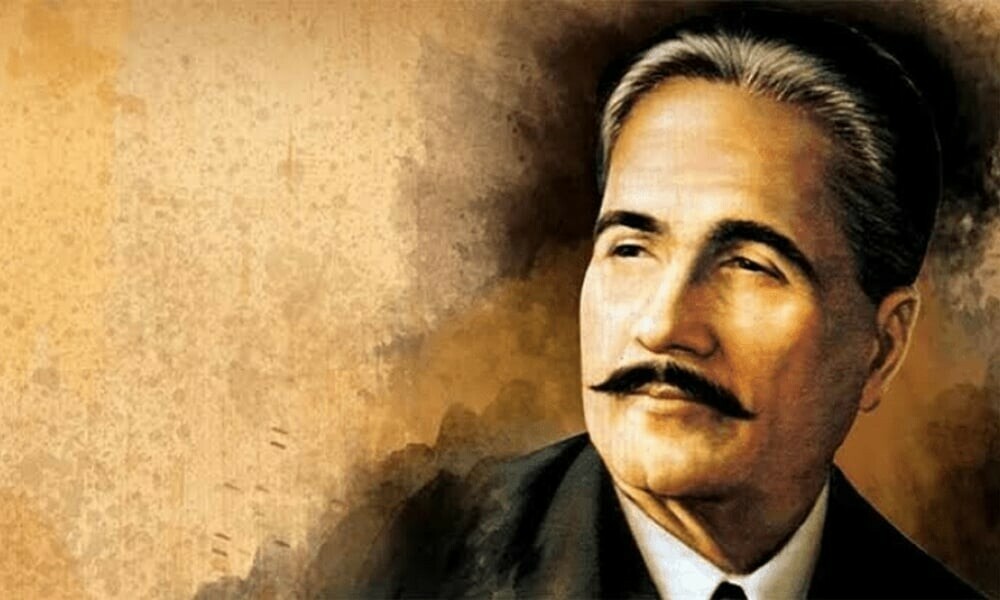

An Iqbalian Critique Of Muslim Politics Of Power: What Allamah Muhammad Iqbal’s Writings Teach Us About Political Change

Published

In 1937, philosopher-poet and perhaps the foremost intellectual of Muslim India, Allamah Muhammad Iqbal, wrote a series of letters to the leader of the All Indian Muslim League and eventual founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

Over the years, Iqbal and Jinnah had come to share a deep respect and admiration for one another – a respect that had not always been the case. When Jinnah agreed to the Lucknow Pact almost 20 years earlier, for example, Iqbal fiercely criticized and refused to acknowledge it.1The Lucknow Pact was an early agreement between the Indian National Congress and the All Indian Muslim League in which Muslims were given greater representation in Hindu-majority provinces in exchange for non-Muslim majority in representative bodies in Muslim-majority provinces. Iqbal was a vocal critic of the pact, as he saw it as a majoritarian ruse of tokenizing Muslims in Hindu-majority provinces in exchange for stripping Muslims of agency in Muslim-majority provinces. Over time, however, Jinnah would recognize Iqbal as “the sage-philosopher and national poet of Islam,”2 Letters of Iqbal, 236 and Iqbal would recognize Jinnah as “the only Muslim in India today to whom the community has the right to look up for safe guidance.”3Letters of Iqbal, 258 When coupled with the poetics of Iqbal, these letters offer us tremendous insight into Iqbal’s own thought, particularly his emphasis on the integration between the theological, cultural, political, economic, and social.

Perhaps the most important of these letters is the seventh, written on the 28th of May, 1937. In this letter, Iqbal confronts the problem of the Muslim League’s popularity with the very population it claims to serve. To Iqbal, the primary problem of India was not simply British rule – it was colonialism as a social, economic, and political ordering of society. In his warning to Jinnah, Iqbal presciently warns the statesman of replacing one colonial class with another. If, Iqbal warns, the offices of the Muslim League are simply made up of aristocrats and their friends and relatives, the Muslim League will not achieve its primary objective: the economic and cultural advancement of Muslims in India. Iqbal warns Jinnah that:

“The league will have to finally decide whether it will remain a body representing the upper classes of Indian Muslims or the Muslim masses who have, so far, with good reason, taken no interest in it. Personally, I believe that a political organization that gives no promise of improving the lot of the average Muslim cannot attract our masses. Under the new constitution, the higher posts go to the sons of upper classes; the smaller ones go to the friends or relatives of the ministers. . .the question therefore is: how is it possible to solve the problem of Muslim poverty? And the whole future of the League depends on the League’s activity to solve this question.”4Letters of Iqbal, 254

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Although the problem of the Muslim League lay in the framework of its governing structures and could be remedied by smart politics, in contrast, Iqbal was deeply pessimistic about Congress’s capacity to do the same for Hindu India. In particular, Iqbal was suspicious of the political leader of the Indian National Congress, Jawaharlal Nehru, and what he called his “atheistic nationalism”:

“I fear that in certain parts of the country, e.g., N.W. India, Palestine may be repeated. Also, the insertion of Jawaharlal’s socialism into the body-politic of Hinduism is likely to cause much bloodshed among the Hindus themselves. The issue between social democracy and Brahmanism is not dissimilar to one between Brahmanism and Buddhism. Whether the fate of socialism will be the same as the fate of Buddhism in India, I cannot say. But it is clear to my mind that if Hinduism accepts social democracy, it must cease to be Hinduism. For Islam, the acceptance of social democracy in some suitable form and consistent with the legal principles of Islam is not a revolution but a return to the original purity of Islam.”5Letters of Iqbal, 2556Iqbal likens the struggle between social-democracy and “Brahmanism” – that is, Brahmanic control of all Indian levers of political and economic power – to the struggle between Brahmanism and Buddhism. Buddhism started in India but never truly flourished there and found most acceptance in non-Hindu regions. Iqbal intimates that this is due to the logic of caste in Hinduism which is incompatible to the core message of Buddhism.

The structure of his argument, and particularly his fierce critique of Nehru, reveals much about Iqbal’s own thinking about society. If the primary objective of politics is the cultural and economic upliftment of society, then that upliftment is dependent on the political structures that organize it; those political structures themselves, however, are dependent on the cultural base that supports it; and that cultural base is dependent on the self-imagination of the members of that society. In his dual critique of both Congress and the Muslim League, Iqbal makes a prophetic assertion: the failure of the Muslim league will be due to the aristocratic and landed-elite’s dominance over the political structure; the failure of the Indian National Congress will be because Nehru’s “atheistic socialism” will create a civil war within “Brahmanism” itself, because the very basis of political structures – culture – will be incompatible with the political structure Nehru will try to erect.

The centrality of caste-based thinking that acts as a lens in the mind of contemporary Hinduism would create significant tensions with Nehru’s utopian socialism; a tension that would eventually erupt in a socio-cultural civil war within Hinduism itself. For the Muslim mind, however, such ideas of “social democracy” as he called it – a shorthand for economic parity and meritocracy – were ideas embedded within the Muslim’s imagination of his own past. The shari’ah itself guaranteed economic justice; the sunnah of the Prophet, peace and blessings be upon him, recommended a meritocratic distribution of labor regardless of lineage.

Iqbal proves prophetic in both his critiques: India, which is embroiled in an intense socio-cultural civil war over the nature of Hinduism, is one of the world’s most unequal countries today; and the military-landholder alliance of convenience that dominated Pakistan’s politics after the assassination of Liaquat Ali Khan in 1951 has concentrated all political and cultural power in the hands of a small aristocratic elite and brought the country to the brink of civil war.

Iqbal would also anticipate the post-colonial and subaltern thinkers who began writing in the 1960s: colonialism is not simply a form of conquest built upon the imagination of a civilizational hierarchy; it is a particular manifestation of a general category of extractionary governance that is built upon the nexus of socio-cultural beliefs and practices that are enshrined in a political structure which extracts economic benefit from the many and collects it in the hands of a few.

Colonialism may have ended in its most explicit forms, but colonialism as a form of governance is more prevalent today than it was in the 1850s.

Neo-Liberal Extraction and the Culture of Capitalism

The fall of the Soviet Union marked a distinctive shift in the world’s socio-economic imagination. There was no longer any need to debate the merits of capitalism and liberal democracy; we had, in the words of Francis Fukuyama, reached the end of history. Liberal democracy and neo-liberal capitalism had clearly demonstrated themselves in a cold-war of social darwinism as the most ideal forms of human socio-economic organization, and all that was left was for the rest of the world to “catch up” to these discoveries. The last 40 years, in general, and 34 years in particular, have been a global experiment on a general cultural framework: individual greed is the driver of all goodness in society.

When Milton Friedman declared that “greed is good,” he also declared that all good is a product of human greed. This thinking has become increasingly indicative of the Western mind, a continuous shift from the glorification of austerity and poverty by the Catholic Church centuries earlier. And, so, as a practice of social, cultural, and political policy, all the Western world has continuously unleashed greed, positioning it not as a vice to be remedied but the primary producer of the greater good of man. And, as always, it is the Quran that is most prophetic:

“Know that this worldly life is no more than play, amusement, luxury, mutual boasting, and competition in wealth and children. This is like rain that causes plants to grow, to the delight of the planters. But later the plants dry up, and you see them wither, then they are reduced to chaff. And in the Hereafter, there will be either severe punishment or forgiveness and pleasure of Allah, whereas the life of this world is no more than the delusion of enjoyment.” [Surah Al-Hadid; 57:20]

Unleashed capitalism, undergirded by a the conception of the self rooted in material individualism (as opposed to Islam’s radical spiritual individualism), has wrought untold destruction on the earth, perpetuated the televised genocide of entire peoples; thrown country after country into social and political upheavel; all in the name of greater capital accumulation which has turned the whole world’s economy into a vacuum that sucks the wealth of the many into the hands of a few.

Returning to our frame story of Iqbal’s letters to Jinnah, and to the greater thinking of the philosopher-poet himself, we are confronted with a significant problematic of our own conceptions. After the genocide in Gaza and the utter ineffectiveness of Muslim politics in all its manifestations – from access-based establishment politics to anti-establishment protest movements – there has been a greater call for Muslims to “create” power. While well-meaning, many of these calls prove to be simplistic and counter-productive in their understanding of achieving power in a thoroughly broken world order.

Projects for wealth generation perpetuate structures of extraction; projects for culture reinforce the structures of material individualism; projects for political participation reinforce the illegitimate dominance of elites over social systems. The discourse of “navigating” the system quickly turns into one reinforcing it – to simply become integrated into a ruling class of destruction to further advance one’s political objectives.

And, yet, power is indeed very powerful; and simply ignoring the mechanisms of power or refusing to participate within them leaves one at the mercy of those who would deploy the levers of power against you. Muslims are therefore trapped in a conundrum that seems impossible to solve: refusing to engage in existing structures is to become exploited by them; engaging in them turns one into a participant in competitive exploitation.

Iqbal’s Relevance Today

This, perhaps, is where Iqbal is most prescient and informative. At the core of Iqbal’s entire philosophical project, one which I will write about more extensively, is a critique of modern modes of social organization as a critique of the very imagination of being itself. To Iqbal, the material reality is created by conceptual understandings; and those conceptual understandings are rooted in an imagination of the self as a purely material being. Where Western thought has seen the world in binaries, the most important of which are the body and the soul, Iqbal, as an inheritor of the Islamic philosophical tradition, rejects every binary possible.

The root of Western dysfunction is the abandonment of the soul, where Christianity abandoned the body. The root of Christian dysfunction is where Christianity abandoned law for spirituality. The root of philosophical dysfunction is where philosophy abandoned intuition for thought. All dysfunction is rooted in imaginations of oppositional binary, where one of two concepts must be chosen at the expense of the other.

In the Quran, however, all matters are integrated: the soul is integrated with the body; the legal is integrated with the material; the material is integrated with the metaphysical. The rectification of human society, therefore, is to remind the human of what they truly are, of what the world is, of what all of reality itself is. The human is most alone when he attempts in vain to find meaning in materiality alone. He is most prone to his own self-destruction – and the destruction of all of the world and humanity itself – when he seeks to fill the God-sized hole in his heart with materiality. It is when man is most estranged from the reality of himself that he becomes entirely estranged from God.

Iqbal encapsulates it best in a couplet, when he says in the Javidnama:

به آدمی نرسیدی ، خدا چه میجویی

ز خود گریختهای آشنا چه میجویی

“You haven’t reached (the reality of) Man;

For what do you seek God?

From one accustomed to fleeing

From himself – what do you seek?”

Man has forgotten himself, so man has forgotten God; but the world only makes sense when it finds its sense in God. The world is in need of a return to God; nothing can escape the need for God – not as a trite contemporary spiritualism which assuages the guilt of materialism, but as an inextricable part of self-imagination that manifests in an ethic of action rooted in passionate pursuit of the love of God.

We lack the love to seek Allah

There is much more to be said, much more to be written, much more to be explored, but, for now, let it suffice to say:

قلندریم و کرامات ما جهانبینی است

ز ما نگاه طلب ، کیمیا چه میجویی

“We are dervishes, and our miracle

Is the ability to see the world

Seek the capacity to see from us –

For what do you seek alchemy?”

Related:

– The Tolling Bell Of Revolution – Why The World Needs Allamah Muhammad Iqbal Now More Than Ever

– Islam, Decoloniality, And Allamah Iqbal On Revolution

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

If a man is what he does, then M. Saad Yacoob is a student (of knowledge and other, less useful things), an aspiring writer, and poet. If it is what he's learned, then Saad is a Bachelor's in English from George Mason University and a PhD Student in Arabic and Islamic Studies at Georgetown University. If he is what he eats, then Saad is currently cake rusk. But, perhaps, a man is not what he does or knows or eats but how he's been formed and who he's come to be. If so, then Saad comes from the land between two rivers and has flowed like water around the world. His lineage may stretch back centuries, but it is like an uprooted tree floating upon the roaring current of a river beset by flood. He is, as his family has always been, a wanderer, liminal in every way.

What Islam Actually Says About NonMuslim Friends | Night 8 with the Qur’an

Ramadan, Disability, And Emergency Preparedness: How The Month Of Mercy Can Prepare Us Before Communal Calamity

Somalis In Firing Line Of American Crackdown

Week 1 in Review: Is Your Teen Actually Changing? | Night 7 with the Qur’an

NICOTINE – A Ramadan Story [Part 1] : With A Name Like Marijuana

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

[Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy

[Podcast] Guardians of the Tradition: Muslim Women & Islamic Education | Anse Tamara Gray

Op-Ed: Bitterness Prolonged – A Short History Of The Somaliland Dispute

What Islam Actually Says About NonMuslim Friends | Night 8 with the Qur’an

Week 1 in Review: Is Your Teen Actually Changing? | Night 7 with the Qur’an

Why Your Teen Wants to Change Their Muslim Name | Night 6 with the Qur’an

The Comparison Trap | Night 5 with the Qur’an

When You’re the Only Muslim in the Room | Night 4 with the Qur’an

Trending

-

#Islam1 week ago

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

-

#Current Affairs1 month ago

[Podcast] Should Muslims Ally with Conservatives or Progressives? | Imam Dawud Walid

-

#Islam4 weeks ago

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

-

#Life4 weeks ago

[Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy