#Culture

Calamity In Kashgar [Part II]: The Rise And Betrayal Of The Second East Turkistan Republic

Published

By

Ibrahim Moiz

[Note: This article makes some use of the administrative term “Xinjiang”, not in recognition of China’s claimed sovereignty but as an administrative description for a sprawling region. Uyghur activists often refer to this region as East Turkistan, a quite fair claim that this usage is in no way intended to contest: for purely descriptive purposes, the term Xinjiang is used when referring to China’s administrative structure]

In the first of this two-part series, we covered the rise and fall of the East Turkistan movement in the 1930s, a hectic period where the Turkic Muslim revolt fell prey both to internecine conflict as well as to the bludgeon of the Soviet Union. In this second part, we will trace the second, and far more controversial, “East Turkistan Republic”, one that was ironically supported and then hung out to dry by the same Soviet Union.

Imperial Sights and Local Aspirations

The intermediate years had not eased Turkic aspirations for their rights in East Turkistan, especially as China’s autonomous “Xinjiang” governor-general Sheng Shicai ruled with increasing oppression. Like his predecessors in Urumqi, he enjoyed and abused his power in what China considered its largest province. To a far greater extent than the 1930s, the 1940s would see this strategic region become the center of conflict between rival powers. Firstly, China’s American-backed Guomindang regime led by Chiang Kai-Shek had fought a long war against the communists led by Mao Zedong: both had interrupted this war to cooperate uneasily against an exceptionally brutal Japanese invasion that spanned most of the Second World War, but by 1941 their cooperation had run its course. In the same year, the Soviet Union joined the war against Japan, forming an equally uneasy coalition with the United States. Moscow had launched an unprecedented war against religion over the last two decades, but in order to mobilize people for the “Patriotic War” against Germany and Japan, they somewhat loosened their grip. For purposes of leverage, the same Soviets who had crushed the Turkic revolts of the 1930s were eager to exploit Turkic grievances against China’s Guomindang regime. The Soviets also allied with nearby Mongolia, with whom China had a border dispute, and this competition drew in many of the Hui Muslims such as the “Ma” clique whose militias dominated China’s north. However, Turkic activists mistrusted the Hui commanders based on the bitter experience in the 1930s.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Sheng Shicai had imitated Soviet brutality, especially against Muslims; he also copied the Soviet method of classifying Turks according to sub-ethnic groups, such as Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and Kirghiz, and it was partly in response that East Turkistan activists had insisted on the name “East Turkistan”, particularly because the region included more than simply Uyghurs. In the early 1940s, Sheng increasingly exhausted the patience of both the Soviets and Guomindang, and in 1944 he was dismissed. Only weeks later, in November 1944 a major Turkic revolt broke out: unlike the 1930s where revolt had taken place in the south, the 1940s revolt took place in “Xinjiang” ‘s largely Kazakh north along the Yili river valley.

A Dramatic Winter

The revolt was led by an uneasy partnership between Islamic leaders, such as scholars Alikhan Tur and Asim Hakim, and pro-Soviet leftists whom Moscow had recently dispatched to put pressure on the Guomindang regime of China. Although the revolt included important leaders of the “Islamic” camp such as the Kanat brothers Latifjan and Muhiuddin – who were sons of Abdulbaqi Sabit, the martyred premier of the first East Turkistan emirate – their importance progressively waned and they came to rely heavily on such Kazakh chieftains in the Altai region as Ali Rahim and Usman Batur, the latter a colorful veteran of a low-running insurgency in the region for years.

The leftist camp included Ahmedjan Qosimi, Saifuddin Azizi, Abdulkarim Abbas, and the military commander Ishaq Mura: they were also joined by Dalilkhan Shukurbayoghlu, a Kazakh chieftain who had been instructed in their ideology; by Zair Saudanov, who served as commissar for their army; and by the Russians Peter Alexanderov, Major-General Bolinov, Colonel Leskin, and Moskolov who assumed key military and security roles. Several commanders from this leftist camp had in fact fought with the Soviets against the first East Turkistan emirate, but now the Soviets found it expedient to set up a second such regime as a buffer force against China. Though they privately expressed contempt for the Islamic leaders, who with typically inaccuracy were dubbed “feudal reactionaries”, the leftists realized that in order to gain public support among Muslims they would have to let the “reactionaries” take the public face of the revolt. Yet the leftists’ own propaganda displayed their real sympathies: one tract blatantly whitewashed Soviet misrule in Central Asia and compared Soviet links to Turks to that of a mother with her newborn child – a comparison that no honest appraisal of the past decade could have made with a straight face.

The revolt quickly captured most of Yili’s main city Kulja, bottling the town’s remaining garrison, led by Du Defu, in its temple over a freezing winter. When in midwinter Du finally attempted to break out and make for the faraway garrison town Jinghe, his force was cut to ribbons: only a fifth of the original five thousand soldiers survived. Reinforcement attempts sent by Li Tiejun from Jinghe were constantly batted off by both the Russian commanders and the Kazakh chieftains, who routed thousands of reinforcement soldiers in the mountains in February 1945. A break ensued as this new East Turkistan regime, based in and thus often named after the Yili river valley, consolidated while internationally, the Guomindang regime of China, backed by the United States, negotiated with the Soviets as the Second World War drew to a close. In the summer of 1945 battle was rejoined: the Kazakh chieftains captured the Altai district of Ashan in full, the key mountain town Tarbagatai was taken, a southern advance by Abbas and Ishaq assisted by Soviet airpower, and the regime’s remaining northern strongholds at Jinghe and Wusu surrounded.

Compromise and its Camps

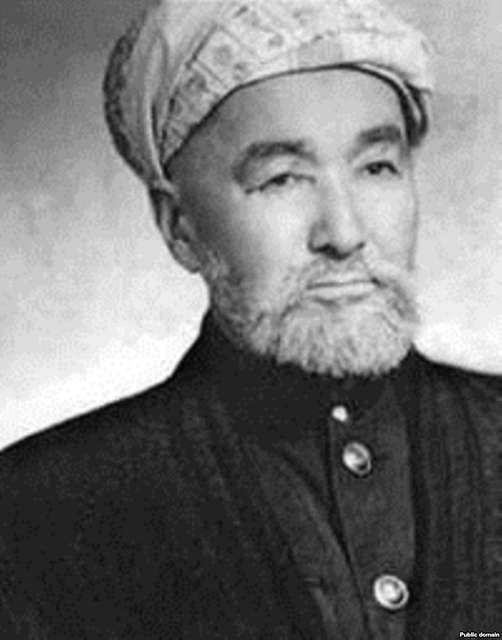

Alikhan Tur, the titular emir of the second East Turkistan emirate who disappeared after refusing to compromise his principles in 1946. (Source: GetArchive.net)

Then, pursuant to Soviet wishes, the advance suddenly stopped at the Manas River in the autumn 1945 and negotiations began with the Guomindang general Zhang Zhizhong. He was unusual in that he viewed the only way to retain control of “Xinjiang” to be a more conciliatory policy with greater Muslim and Turkic representation, as well as friendly links with the Soviets. The negotiations lasted months until the summer of 1946, but they greatly disturbed East Turkistan emir Alikhan Tur who had hoped to liberate the entire Turkic region rather than come to such a compromise: in turn, the pro-Soviet leftists in Yili lashed out at him and castigated him as a “reactionary”. When at the summer’s end Alikhan suddenly vanished without trace, the leftists speculated that he must have gone to the Soviet Union for medical treatment. In fact he was probably “liquidated” by the Soviets, a likelihood not lost on his successor Asim, who avoided antagonizing the leftists.

The negotiations resulted in a coalition government for “Xinjiang” led by Zhang Zhizhong, with the northern Yili valley remaining a largely autonomous region: they planned elections to make “Xinjiang” more representative and steadily water down the historical Han overrepresentation in government. Governor-general Zhang and his advisor Liu Mengchan were flanked by the Turkic leftists Qosimi and Burhan Shahidi – a supporter of the 1934 Soviet invasion. Other leftists included Abbas, Azizi, Dalilkhan, and Ishaq, but Zhang also brought in Muslims who opposed the Soviets and instead sided with the Guomindang as a preferable alternative.

They included the Turkic nationalist Masud Sabri, whose nephew Rahimjan was actually a negotiator for the Yili rebels but who himself was seen by the leftists as a “reactionary”: he became inspector-general. This camp also included Amin Bughra, who had led the first East Turkistan emirate, and Isa Alptekin, who had opposed it; Yulbars Khan, a veteran of the 1930s revolt at Kumul; and Jalaluddin Wang, a Hui merchant who had financed the 1930s revolt; and Amin’s wife Emina Baigum. It also included a number of Kazakhs – including Liu’s deputy Salis Emreoghlu and provincial treasurer Janimkhan Talaobayoghlu; Urumqi sheriff Khadija Kadvan and her husband Ailan Wang at Altai. Salis and Janimkhan had helped negotiate with the Kazakh chieftains in Altai. A Hui Muslim preacher, Ma Liangjun, was given honourary privileges, and there was some effort to end Han soldiers’ depredations toward Muslims – for example, a ban would be placed on unIslamic marriages between Muslim women and Han men in Kashgar.

However this coalition was inherently unstable: the majority of Zhizhong’s year in Urumqi (1946-47) was spent in tussles between leftist and rightist Muslims, each of whom appealed for the others’ dismissal. While the leftists were backed by the Soviets, ironically the rightists were partly supported by Guomindang corps commander Song Xilian, who himself disliked the Muslims but feared that the leftists would act as a “fifth column” against China to space out Han from positions of power. In February 1947 Song put Urumqi under emergency rule after protests escalated into ethnic violence.

In the south, Kashgar commander Yang Deliang – a Han general who had converted to Islam – incited protests against leftist sheriff Abdulkarim Maksum. In the east Turfan’s leftist sheriff, Abdurrahman Muhiti, and Uyghur activist Namanjan Khan led protests that allegedly escalated into revolt before the army violently cracked down.

In the north, Kazakh chieftains Usman Batur and Ali Rahim launched a revolt, claiming to fight Soviet tutelage, against the leftists alongside whom they had formerly fought in 1944-45. In the summer of 1947 Usman, along with Hui generals Ma Chengxian of the famous “Ma family” and Habibullah Youwen, raided the Baytash Boghd region on the border of Mongolia. The Soviets had long supported Mongolia’s territorial dispute with China, and so this was treated as an international incident backed by China’s Guomindang regime.

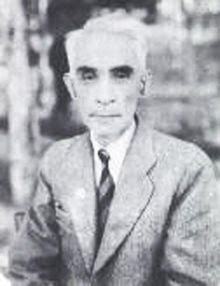

His support for Guomindang as a counterweight to the communists made “Xinjiang”‘s first Turkic governor-general, Masud Sabri, a target of the leftists. (Source: Centre for Uyghur Studies)

By this point a harried Zhizhong had resigned in favor of Masud, on whom Qosimi and the other leftists now trained their gunsights, forcing him to rely more and more on an army whose prestige was crumbling. In early 1949 Masud was replaced, to the rightists’ dismay, with Tatar leftist Burhan Shahidi: this coincided with the Guomindang collapse in China. Over the course of 1949 Mao Zedong’s communists routed Guomindang forces throughout China, including many of the Hui troops who had led it in the north. Many generals, including former Xinjiang governor-general Zhizhong and Hui commander Youwen, ended up defecting to the communists. At this early stage, Mao had won over much of China’s countryside, and unlike the Guomindang, he promised to give autonomy and respect minority rights. When a plane crash in the summer of 1949 killed Qosimi, Abbas, Ishaq, and Dalilkhan, it left Xinjiang governor-general Shahidi and Yili emir Azizi as the leading leftist Turks, and they had no hesitation in welcoming Mao’s vanguard that autumn. The second “East Turkistan” emirate, always a plaything between rival international powers, thus faded with a whimper.

Aftermath and Lessons

In spite of Shahidi and Azizi’s confidence in communist solidarity, by the mid-1950s Mao’s China was beginning to extend its control and the promised autonomy soon became a thing of the past. Instead, the Turkic leftists were left as simpering puppets for an increasingly brutal regime, whose Han commander Wang Zhen viewed Uyghurs in particular as natural troublemakers and intensified the worst practices of the past. Only in the 1980s, with some Pakistani mediation, did China permit “Xinjiang”’s Muslims to return to the Islamic pilgrimage, but by the late 1990s calls for independence or autonomy resumed, as did a very low-level insurgency that consisted of occasional knife attacks, and China again increasingly cracked down – a process that reached a terrifying extent in 2016 when the communist party put virtually the entire Uyghur people under tightly surveilled “re-education” camps to drain them of their supposed radicalization. In fact, the “East Turkistan Independence Movement” never had much of a presence at all within its homeland, and has largely been restricted to faraway battlefields such as Afghanistan and Syria.

But if the leftist alliance had failed, rightist prospects had hardly been more promising. The Guomindang regime had been expelled by the communists to Taiwan, whereas an American vassal it continued to stake its claim to China. Various Muslim commanders including Yulbars Khan, Usman Batur, and many Hui generals joined Guomindang ranks and, with American support, led an insurgency against the new communist regime till many of them were killed in battle. Unlike Yulbars, Isa Alptekin and Amin Bughra tried to persuade the Guomindang regime in Taiwan to give up its claim to “Xinjiang”: when this failed, the pair instead traveled to Turkiye where they would continue to advocate for East Turkistan’s independence. Alptekin, who had opposed both the first and second East Turkistan emirates, now fervently argued for East Turkistan’s complete independence: after he passed away, his son Erkin set up an “exile government” of sorts, the World Uyghur Congress, at the United States with considerable American support in 2004. The political trajectories of such exile leaders mean that their impact on the ground among Uyghurs and other Turkic groups is limited.

There are many lessons that can be learned from the short-lived East Turkistan Republics of the 1930s and 1940s. Perhaps most notably, its leaders too often failed to honor their Islamic rhetoric and instead engaged in bitter internecine conflict: whether between Turks and Hui in the 1930s or between rightists and leftists in the 1940s. Secondly, its strategic location meant that self-interested foreign powers were never far away: especially revealing is the cynical role of the Soviet Union, who crushed the first emirate in the 1930s, and then adopted the role of the second emirate’s “mother” in the 1940s only to discard it when it outlived its use. Such uncomfortable alliances, with all the contradictions they entailed, were only made necessary because of the remoteness of this eastern corner of Central Asia. Today, in an age of expanded communications and potential awareness, the people of East Turkistan need greater solidarity from Muslims: it is only through such shared interests, through principled solidarity and faith in Allah

Related:

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Ibrahim Moiz is a student of international relations and history. He received his undergraduate degree at the University of Toronto where he also conducted research on conflict in Afghanistan and Pakistan. He has written for both academia and media on politics and political actors in the Muslim world.

The Art of Tadabbur: Enriching Our Relationship With The Quran

Why Do Bad Things Happen to Good People? | Night 18 with the Qur’an

Revolutionary Philosopher And Potentate: The Life And Polarizing Legacy Of Ali Khamenei

Is Depression a Lack of Faith? A Guide for Muslim Parents | Night 17 with the Qur’an

When Ramadan Arrives To Heal What Life Has Broken

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

Where Does Your Dollar Go? – How We Can Avoid Another Beydoun Controversy

An Unending Grief: Uyghurs And Ramadan Under Chinese Occupation

Who Am I Really? What Surat Al-‘Asr Teaches Muslim Teens About Identity | Night 1 with the Qur’an

Ramadan In The Quiet Moments: The Spiritual Power Of What We Don’t Do

Why Do Bad Things Happen to Good People? | Night 18 with the Qur’an

Is Depression a Lack of Faith? A Guide for Muslim Parents | Night 17 with the Qur’an

I Can’t Feel Anything in Prayer – Understanding Spiritual Dryness | Night 16 with the Qur’an

Every Sin Has a Cure | The Venom and the Serum Series

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Someone | Night 10 with the Qur’an

MuslimMatters NewsLetter in Your Inbox

Sign up below to get started

Trending

-

#Islam3 weeks ago

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

-

#Life1 month ago

[Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy

-

#Islam1 month ago

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

-

#Islam1 month ago

[Podcast] Guardians of the Tradition: Muslim Women & Islamic Education | Anse Tamara Gray