#Islam

Behind The Differences In Contemporary Masahif

Published

As we head to our local masjid this Ramadan, we will invariably find ourselves searching the bookshelves for a muṣḥaf, or a printed copy of the Qurʾān. There is often a wide array of options, and everyone is looking for one that looks familiar to them, while half wondering what exactly the difference is between all these copies of the Qurʾān. As we do each year, we will probably put the thought aside, find the muṣḥaf we are most comfortable with, and begin reading.

This article hopes to offer some answers to the question that seems to appear and then disappear each year. What exactly is different about contemporary copies of the Qurʾān? For the purpose of this article, we will be comparing the Madinah printed muṣḥaf in the Naskh script and the South Asian printed muṣḥaf that is published in India and Pakistan, both in the narration of Imam Ḥafṣ. It is important to make this distinction as there are other maṣāḥif in the world that share similarities with the South Asian muṣḥaf, such as the calligraphic script and diacritics of the South African printed maṣāḥif, the signs for stopping in the Turkish printed maṣāḥif, or the diacritics in the Indonesian maṣāḥif. The King Fahad Qurʾān printing complex also prints a muṣḥaf that is very similar to the South Asian printed maṣāḥif. In order to ensure that there is no confusion, and we are able to delve into this topic in some detail, we will limit our comparison to the two maṣāḥif mentioned above.

Calligraphic Script

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

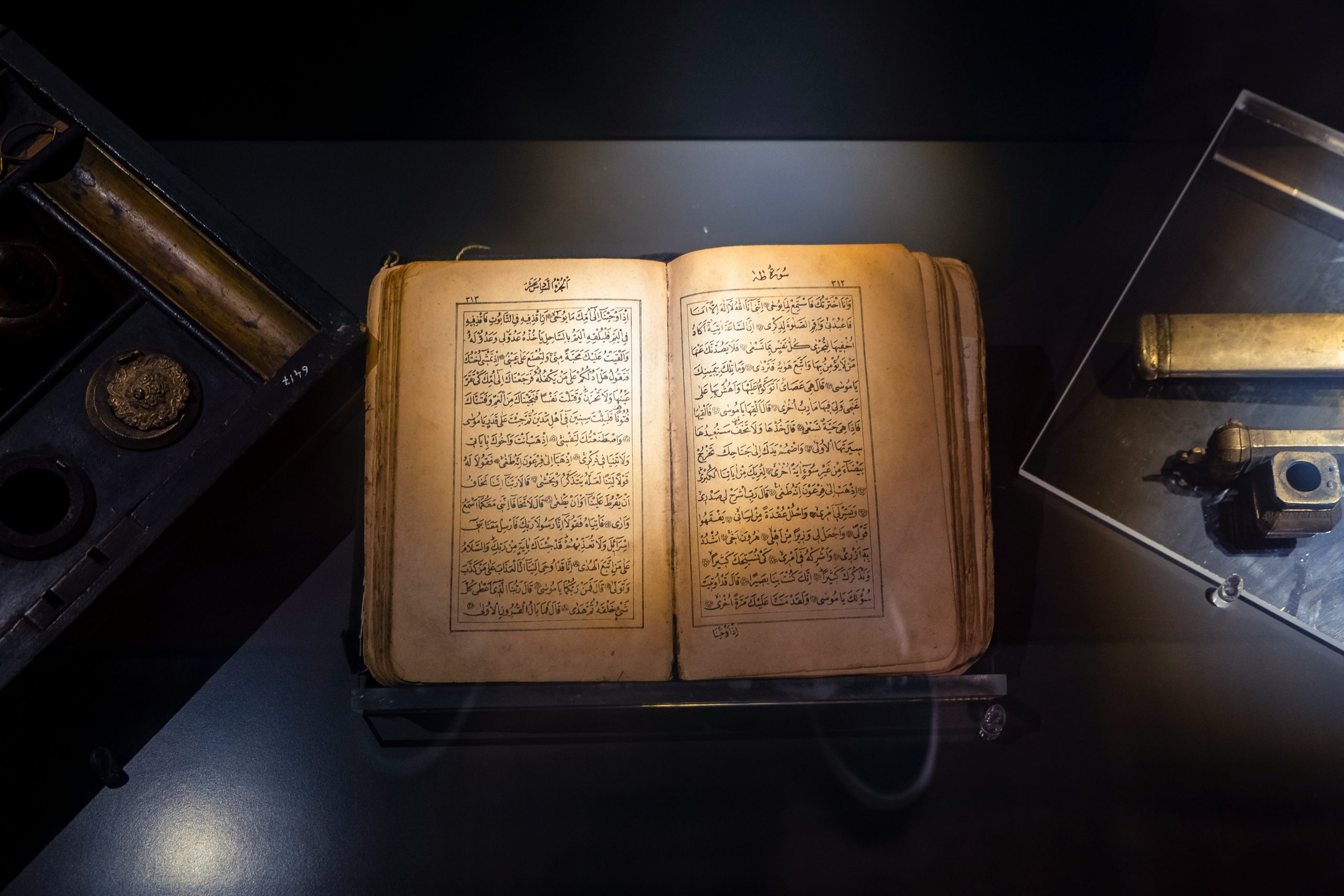

The most obvious difference when looking at the two maṣāḥif is their calligraphic script. The Qurʾān has been written in many calligraphic scripts throughout Islamic history and this continues to the present day. The Ḥīrī script, later called al-Khaṭṭ al-Ḥijāzī, was one of the earlier scripts in which the Qurʾān was written. As Islam spread, Muslims developed other calligraphic scripts as well, such as the Kūfī script.1M. Mustafa Al-Azami, The History of the Qurʾānic Text (Riyadh: Azami Publishing House, 2011), 139; ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ al-Qāḍī, Tārīkh al-muṣḥaf al-sharīf (Cairo: Al-Azhar, 2015), 7-8.

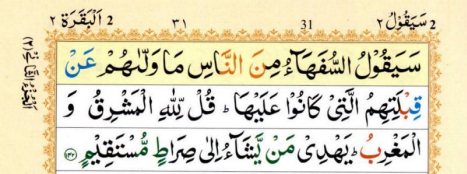

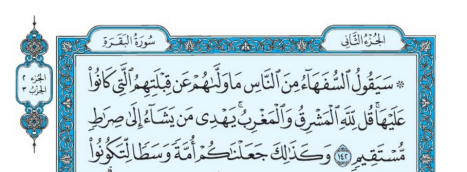

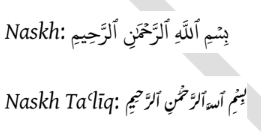

Among the Arabic calligraphic scripts are Naskh and Naskhtaʿlīq or the hanging Naskh. The Qurʾān may be written in any calligraphic script of Arabic. While the Madinah printed muṣḥaf is written in the Naskh script, the South Asian printed muṣḥaf is written in the Naskhtaʿlīq script.

Rasm al-Khaṭṭ

While the calligraphic script of the Qurʾān can differ, the rasm or orthography of the Qurʾān should not.2Abū ʿAmr al-Dānī, al-Muqniʿ fī maʿrifat marsūm maṣāḥif ahl al-amṣār (Cairo: Dār Ibn Kathīr, 2018), 35; Jalāl al-Dīn al- Suyūṭī, al-Itqān fī ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān (Cairo: Dār al-Salām, 2013), 939. Rasm is the science of the Qurʾān that preserves the unique spellings of the Qurʾān. While most of the Qurʾān is written according to normal Arabic spelling conventions, there are some words that have a unique orthography. This unique orthography is according to how the Qurʾān was written by the ṣaḥābah in the presence of the Prophet

The science of rasm preserves the outlines of the words of the Qurʾān. This means the words of the Qurʾān without any of the dots for letters, or markings for vowels. This is how the ṣaḥābah wrote the Uthmanic codices. They did so to incorporate the canonical recitations of the Qurʾān.4Qāsim ibn Firruh al-Shāṭibī, ʿAqīlat Atrāb al-Qaṣāʾid fī Asna al-Maqāṣid, l. 35. As, although Arabs did not have diacritics for vowels at the time, they did have dots to distinguish certain letters, and yet the ṣaḥābah chose not to use them.5M. Mustafa Al-Azami, The History of the Qurʾānic Text (Riyadh: Azami Publishing House, 2011), 151.

To demonstrate what the rasm of a word is, we will take the example of the word

This word carries vowel markings and the letters yāʾ, bāʾ and nūn also carry dots. However, it is only the skeletal outline of the word that is considered the rasm of the Qurʾān,

Therefore, while the skeletal structures of words in the maṣāḥif cannot differ beyond what has been reported from the Uthmanic codices, the dots for letters and vowel markings may differ as these were developed later, and they will be discussed in the next section.

South Asian Printed Musḥaf in the Naskhtaʿlīq script

Scholars have ascertained the various acceptable ways in which the words of the Qurʾān may be written by observing the Uthmanic codices, as well as by preserving the oral reports from the scholars that observed them. In the centuries of scholarship that we have on this science, we find that there are certain unique spellings that are agreed upon, meaning that they can only be written in one way, while others were written in two or more possible ways by the ṣaḥābah. This is what we refer to as a khulf. When such a khulf exists within the science, contemporary scholars who are publishing copies of the Qurʾān must choose between one or the other. They obviously cannot write the same word twice. In order to streamline this process, they generally choose to rely on the preferences of one classical scholar. While the Madīnah printed muṣḥaf follows the preferences of Imam Abū Dāwūd Sulaymān Ibn Najāḥ (d. 496 AH), the South Asian printed muṣḥaf follows the preferences of Imam Abū al-Qāsim al-Shāṭibī (d. 590 AH).6Muḥammad Shafāʿat Rabbānī, “Bare ṣaghīr aur ʿarab mumalik main ṭabʿ shudah maṣāḥif ka rasm al-khaṭṭ: ʿilmī aur tabābulī jāʾizah,” al-Qārī (June 2022): 10-18. While there are many examples of this, we will present only one here. The two words أين ما can be written separately or joined in āyah 78 of Sūrah al-Nisāʾ. These two words are written as separated in the South Asian maṣāḥif according to the preference of Imam al-Shāṭibī.7Qāsim ibn Firruh al-Shāṭibī, ʿAqīlat Atrāb al-Qaṣāʾid fī Asna al-Maqāṣid, l. 256. However, they are written as one word in the Madīnah printed muṣḥaf according to the preference of Imam Abū Dāwūd ibn Najāḥ, as

This is why the rasm of the two maṣāḥif will differ in some places.

Dabt

Unlike the science of rasm, which comes from how the Qurʾān was written by the ṣaḥābah in the presence of the Prophet

The ḍabṭ of the South Asian muṣḥaf and Madīnah printed muṣḥaf differ greatly, and this is often a cause of confusion for those who learned to read with one muṣḥaf and then try to read from the other. One main difference is the way that the letter hamzah is expressed. The first point to remember is that the letter hamzah did not have a unique shape in the Arabic script when the Qurʾān was bring revealed and written.9Ibn al-Jazarī, al-Tamhīd fī ʿilm al-tajwīd (Beirut: Resālah Publishers, 2001), 115. It was either written as an alif, a wāw or a yāʾ or was sometimes absent from the outline of the word altogether. The Arabs also had many variations in the way in which they pronounced hamzah, and these were incorporated in the way that the hamzah was written.10Abū ʿAmr al-Dānī, al-Muqniʿ fī maʿrifat marsūm maṣāḥif ahl al-amṣār (Cairo: Dār Ibn Kathīr, 2018), 107. Therefore, this difference between the two contemporary maṣāḥif is perfectly permissible.

The Madinah printed muṣḥaf marks every hamzat al-qaṭʿ (a hamzah that will always be read in a word) using the head of ʿayn, e.g.,

It marks hamzat al-waṣl (a hamzah that will only be read when starting from the word) with a small ṣād, e.g.,

However, the South Asian printed muṣḥaf employs a different method. If the hamzat al-qaṭʿ is represented by an alif, the ḍabṭ of the South Asian muṣḥaf places a vowel on the alif to represent a hamzat al-qaṭʿ and leaves a hamzat al-waṣl empty of any vowel, e.g.,

There are, however, some hamzat al-waṣl that carry a vowel as well, but these carry a vowel because they occur after a strong sign of waqf, e.g.,

It is assumed that the reader will make waqf before the word. This makes it much easier for non-Arab Muslims to read the word correctly when starting from it, as they may not be as comfortable with reading the correct vowel on a hamzat al-waṣl that is empty of any vowel marking.

Another difference is whether the shape for alif which is part of the rasm of the word will be considered an alif of madd or the shape for hamzah. For example, in the word,

the outline of the word allows for an alif, a mīm, a shape for nūn, and an alif at the end, as امٮا. The ḍabṭ of the Madīnah printed muṣḥaf presents the alif as a letter of madd, and it adds the head of ʿayn as a hamzah. However, the ḍabṭ of the South Asian printed muṣḥaf presents the alif in the outline of the word as the shape for hamzah and adds a dagger alif to represent the alif of madd, as

One is not superior to the other. Rather, it is simply the different ways in which the scholars of ḍabṭ have allowed Quranic words to be marked so that they are pronounced correctly by a non-specialized reader.

For those interested in reading more about the history of the development of the Arabic script and other related topics, please read Tashīl al-Rusūm and Tashīl al-Ḍabṭ in English by Mufti Mohamed-Umer Esmail (May Allah have mercy on him). PDFs of these two works can be downloaded for free from www.qiraatsimplified.com.

Waqf Signs

Madīnah Printed Muṣḥaf in the Naskh Script

As we all know, where we stop in a sentence can change the way that the listener understands it. At times, an oddly placed pause makes the sentence incomprehensible. Similarly, where we stop in the Qurʾān is important to prevent the meaning from being incomplete or misunderstood. We know from a narration of ʿAbdullah ibn ʿUmar

Keeping this diversity in mind, we now look at the two maṣāḥif. The South Asian muṣḥaf generally follows both the symbols for stops as well as the places of stopping of Imam Muḥammad ibn Ṭayfūr al-Sajāwandī (d. 560 AH). It is important to note that it also has many other symbols of stops in it as well, and these are not from Imam al-Sajawandī. Only the symbols لا, ز ,ص ,ج ,ط ,م may be attributed to the respected Imam.13Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī, al-Itqān fī ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān (Cairo: Dār al-Salām, 2013), 1:224. One of the benefits of Imam Sajāwandī’s system of stops is that they are plentiful, and include two categories, marked by ص and ز where it is highly preferable that the reciter continues reciting. However, these two categories allow those who suffer from shortness of breath to have some extra places to stop that will not alter or corrupt the intended meaning of the verse. As these kinds of stops are missing in the Madīnah printed muṣḥaf, one may notice that the places for waqf are far fewer than in the South Asian muṣḥaf.

Above was an explanation of the symbols and places of stopping in the South Asian printed muṣḥaf. While the Madīnah printed muṣḥaf also uses ج ,م ,لا, it has two additional symbols that are different from the South Asian muṣḥaf. These are قلے and صلے . The Madīnah printed muṣḥaf uses the symbols for stopping as they were formulated by the committee that King Fuad I of Egypt had commissioned to publish a copy of the Qurʾān. This committee worked under the guidance of the great Qārī, Shaykh Muḥammad ʿAlī Khalaf al-Ḥussainī al-Ḥaddād (d. 1357 AH).14ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ al-Qāḍī, Tārīkh al-muṣḥaf al-sharīf (Cairo: Al-Azhar, 2015), 52-53. However, while the stop signs used in the Madīnah printed muṣḥaf are the same as these, the places of stops are determined differently than the muṣḥaf that was commissioned by King Fuad I. Shaykh Muṣāʿid al-Ṭayyār, whose book was published in 1431 AH, writes that the Madīnah printed muṣḥaf relies heavily on not only the symbols but also the places of stopping that were marked in the muṣḥaf commissioned by King Fuad I. However, it differs in five hundred fifty-five places, where the scholars of the committee publishing the Madīnah muṣḥaf gave preference to what they understood to be more correct. The information pages of a Madīnah muṣḥaf published in 1439 AH, during the reign of King Salmān, mention that the committee that oversees the publishing of the Madīnah printed muṣḥaf relied on what was said by scholars of tafsīr, books of waqf such as Allāmah al-Dānī’s work al-Muktafā and Abū Jaʿfar al-Naḥḥās’s al-Qaṭʿ wa al-Iʾtināf, as well as what is found in maṣāḥif that were published earlier. Taking both of these sources into account, we can conclude that the places of stopping in the Madīnah printed muṣḥaf do not rely on one classical or contemporary source.15Muṣāʿid al-Ṭayyār, Wuqūf al-Qurʾān wa atharūhā fī al-tafsīr (Madīnah: King Fahad Publishing Complex, 1431 AH), 251.

As scholars differ on the interpretation of the verses of the Qurʾān, they also differ in the determination of the appropriate places to stop.

These are the differences in the symbols of stops and where there are placed. However, there are some other differences as well, such as the Madīnah printed muṣḥaf does not have any recommendations for stops at the ends of verses, which encourages the reader to stop at the end of every verse. However, the South Asian printed muṣḥaf reflects the connection between the meaning of the verses and those with a strong connection in meaning and grammar are marked with a

to encourage the reader to continue reciting. This can be helpful for those memorizing the Qurʾān. Some teachers encourage students to read through the ends of verses while memorizing to strengthen the connection between verses in their memory as well as to memorize the vowel on the last letter of the word at the end of a verse. As each verse end is marked with a symbol for stopping or continuing, the reciters know which verses can be joined and which ones should not be joined.

For more information on the science of waqf and ibtidāʾ, please see Maintaining the Meaning: An Introduction to Waqf and Ibtidāʾ. It is free to download at www.recitewithlove.com.

Divisions of the Qurʾān

Conclusion

What has been presented in this short article are some of the major ways in which the two contemporary maṣāḥif differ. All of their differences are supported by centuries of scholarship, and the understanding of reliable scholars. It is important to remember that even with all these small differences, the words of the Qurʾān in both copies remain the same. They are both the words of Allah

I would also like to remind the reader that while this was a comparison of two contemporary copies, a similar analysis could be done with other maṣāḥif from other parts of the world, such as North Africa. These would be the main categories in which the maṣāḥif would differ.

The Ummah finds itself in dark times, and we need the strength that comes from unity and goodwill among believers to persevere through our trials. I pray that Allah

Related:

– Structural Cohesion In The Quran: Heavenly Order

– Pursuing Islamic Scholarship Alongside Another Career? Guidance For Aspirants | Dr. Hatem El Haj

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Ustadha Saaima Yacoob is a teacher, and an author and editor of books on Tajwid, Qira’at, Rasm, and Waqf and Ibtida'. She holds multiple ijazat to teach Tajwid and Qiraat from her teachers in the United States as well as in Jordan and Pakistan. She did her Bachelor's in English and her Master's in Education with a focus on Curriculum and Development from George Mason University. With over two decades of teaching experience, she is the founder of Recite With Love, an online institute for Quranic education. She lives with her husband and son in North Carolina.

Courting The Crosswinds: The Tragedy Of Saif Al-Islam Qaddafi

Parenting Through Times Of Fear, Injustice, And Resistance: A Trauma-Informed, Faith-Centered Guide

Recognizing Allah’s Mercy For What It Is: Reclaiming Agency Through Ramadan

[Podcast] Dropping the Spiritual Baggage: Overcoming Malice Before Ramadan | Ustadh Justin Parrott

Far Away [Part 8] – Refugees At The Gate

[Podcast] Should Muslims Ally with Conservatives or Progressives? | Imam Dawud Walid

Op-Ed: From Pakistan To Gaza – Why Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan Terrifies Power And Zionism

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

[Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy

Keeping The Faith After Loss: How To Save A Grieving Heart

[Podcast] Guardians of the Tradition: Muslim Women & Islamic Education | Anse Tamara Gray

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

[Dhul Hijjah Series] Calling Upon the Divine: The Art of Du’a (Part 1)

IOK Ramadan 2025: Four Steps | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Do Your Best | Sh Zaid Khan

MuslimMatters NewsLetter in Your Inbox

Sign up below to get started

Trending

-

#Current Affairs1 month ago

An Iqbalian Critique Of Muslim Politics Of Power: What Allamah Muhammad Iqbal’s Writings Teach Us About Political Change

-

#Current Affairs4 weeks ago

[Podcast] Should Muslims Ally with Conservatives or Progressives? | Imam Dawud Walid

-

#Current Affairs4 weeks ago

Op-Ed: From Pakistan To Gaza – Why Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan Terrifies Power And Zionism

-

#Culture1 month ago

The Muslim Book Awards 2025 Winners

Shoaib

March 21, 2024 at 1:21 PM

Thank you for this detailed article. I get frustrated when some people mistakenly call mushafs printed in the Arab world “Uthmani” and mushafs printed in South Asia as “Persian”, as though the South Asian masahif are somehow deficient or unauthentic. Rather, s this article explains, both mushafs conform to the Rasm Uthmani, and differ in other allowed ways. I have seen that some non Arabs are ashamed of the mushafs produced in their local lands by the scholars of their regions.