#Islam

Sh. Qasim Hatem’s Road From The Rose Bowl To Religion

Published

At the moment he accepted that he was going to die on the cold bathroom tile of his college apartment, a life that had revolved around football for Qasim Hatem found a familiar and yet entirely new focus.

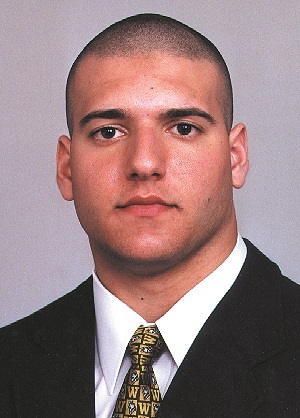

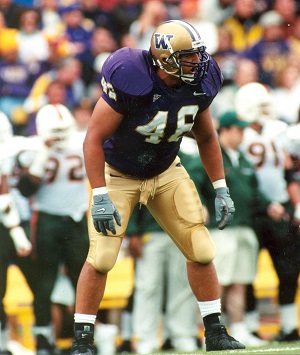

In the spring of 2001, Hatem was a 20-year-old defensive lineman at the University of Washington, a 6-foot-3, 285-pound force in the trenches for the reigning Rose Bowl champions. Going into his redshirt junior season for the Huskies, Hatem was beginning to draw the attention of NFL scouts and college football kingmakers.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

And then one morning, Hatem woke up experiencing sharp chest pains. With each abbreviated breath he took into his massive chest, he found it harder to get oxygen. Making his way to the bathroom, he was physically unable to call for help from his roommates.

Hatem realized he was about to die. He looked into the mirror and told himself that was it. He was done.

“The most valuable things to me crossed my heart at this moment of death and only one stuck,” Hatem recalls about that morning. “I thought that I couldn’t die yet because I have school, football, friends, family, my mother, religion … It was religion that stuck with me and was the most important and valuable thing to me.

“So at the point of death, I dropped to my knees in the bathroom and I recited the first and most important pillar of Islam called the shahadah: ‘I bear witness that there is no God except Allah and that Muhammad is His messenger.'”

Hatem doesn’t remember how long he repeated the shahadah — perhaps half an hour, he estimates — but eventually the fact that he was still alive struck him as a message that Allah was giving him another chance.

Crawling out of the bathroom, the young and extraordinarily fit athlete who had been breaking school records in the Husky weight room just weeks earlier couldn’t muster the strength to climb a flight of stairs. Hatem was finally discovered by a roommate and rushed to the hospital.

After bringing Hatem back from the brink, doctors ran tests and eventually found three large blood clots—pulmonary embolisms—in his lungs. They said the chance of surviving an attack like Hatem had survived, given the size of the clots, was one in a million.

Hatem would have to miss the upcoming football season while being placed on blood-thinning medication. When a nurse told him to prepare himself for the reality that he may never play the sport again, Hatem cried uncontrollably.

“I thought my life was over because I could not play football,” Hatem says.

Hatem focused on school while sitting out the 2001 season and was eventually given medical clearance to return to the field in 2002. But in his time away from the game, Hatem had expanded his worldview and began to see football for just that —a game.

“I was so caught up with the fame and glory of football that I didn’t have much time for religion,” says Hatem, who was raised Muslim during his early childhood in Iowa and practiced semi-seriously as a three-sport high school star in Spokane, WA.

“It did cross my mind though that there is more to life than this,” Hatem says of his mindset during his scheduled hiatus. “Still though, I had been playing football since I was 11 years old. It was my life. It was what I loved and put most of my time into. I thought it was my purpose.”

With two years of college eligibility remaining, Hatem decided to quit football. He finished his undergraduate degree in psychology and, trying to figure out the next step, had another religious epiphany that inspired him to travel to Yemen and study abroad.

At the Badr Language Institute in Tarim, Hatem studied Arabic. He then enrolled at the prestigious Dar al-Mustafa school for an intensive study of Islam and the Quran. He stayed in Yemen for seven years before returning to the U.S. with licenses to teach Islamic jurisprudence (Shafi’i fiqh), Islamic creed (aqeedah), the Arabic language, Quranic recitation (tajweed) and methodology of inviting others to Islam (dawah).

“I came back [from Yemen],” Hatem says, “with the intention to show people who the Prophet Muhammad really is and what Islam really says.”

Today, Hatem is recognized as a leader in the Pacific Northwest’s Muslim community. He is the executive director and resident scholar for the Mihraab Foundation in Seattle. He counsels hospital patients and prison inmates, mentors teenagers and teaches elementary-school kids.

Taking some rare down time to sit for an interview at the Islamic Center of Eastside in Bellevue, WA, Hatem talks about the value of what’s he has been doing since he walked away from a million-dollar opportunity:

[divider]————————[/divider]

MUSLIMMATTERS: For lack of a better way to put it … What do you do?

SH. QASIM HATEM: Alhamdulillah, I’m a servant. I serve Allah

Primarily, my focus is on education and the youth. I’m the resident scholar, executive director and chairman of the board of trustees for an organization called the Mihraab Foundation, which is an Islamic non-profit organization. Our mission is to promote traditional Islam in a Western context. We have two main branches: the youth branch and the scholastic branch. We do a series of classes, conferences, workshops, those kinds of things, for the scholastic branch; and we do youth programs, camps, social activities and other things for the youth branch.

So there’s the Mihraab Foundation, and I’m a teacher, a public speaker, a caller or inviter to Allah and Islam. That’s kind of what you’d say I do in terms of my work and my service. But I don’t consider what I do a job. I consider it a duty, an obligation. I consider it part of my faith. So I don’t wake up and say, “I’ve got to go to work.” I say, “I have to fulfill my obligation to Islam.” I’m going to do this work with or without an organization, with or without structure or a place. I’m gonna do it anyway.

I try to fulfill community needs. If somebody has a fiqh question, if somebody wants a marriage, if somebody needs a funeral procession, I’ll try to help. Any issues, questions or conflicts between husband and wife, or between families, I’ll try to help.

I’m also the Muslim chaplain for Harborview Hospital and the University of Washington Medical Center, and I’m the Muslim chaplain for the corrections facility in Shelton (WA). Any Muslim who is sick or dying, I’m basically on-call to sit with them, to comfort them, maybe pray or make du’a with them, read the Quran and so forth. Sometimes it’ll be non-Muslims who request an imam or a shaykh, and sometimes they want to convert to Islam. In that state where they’re sick or dying, people often have strong realizations about life and now they want to make the right decision. They believe Islam is the truth and want to become a Muslim in that vulnerable time when they’re not sure if they’re going to live or not.

And I’m going to Seattle University as a graduate student in the School of Theology and Ministry for a Master of Arts in Transformational Leadership degree. I’m in my second year of a three-year program.

MM: Why are you pursuing a master’s degree?

SQH: I was trained for seven years in Yemen at a school that disseminates traditional Islamic knowledge. Now I’m going through “imam training” or pastoral training through a Western, Christian university. It’s interesting to combine Western teachings with Eastern Islamic teachings. It’s quite powerful to contextualize traditional Islam in a way people can understand it today in the world we live in.

MM: Could you do what you do effectively without both sides of that education? If someone only went to school in the East without going to school in the West, or vice versa, can they be an impactful imam or sheikh in America?

SQH: I think it’s possible, but it probably would be harder.

One helps the other, supports the other, but the base and principle is traditional Islamic knowledge. Somebody couldn’t be a scholar or imam in any facet if they didn’t have the traditional Islamic training and education from scholars of the tradition that goes back to the Prophet Muhammad. But it’s also important that once they learn this, they can apply it to the society and culture they live in.

It doesn’t mean they compromise religion or compromise Islam, but how do they contextualize and understand it within their society and culture? That is where the secular sciences come in, where (Western) academic institutions and chaplaincy programs come in. To go through those programs helps you understand society and culture better. It helps you use certain terminology and understand interpretations to better serve people and educate them about Islam.

It comes back to an interesting view that was told to me by somebody, which is that you have the text and you have the context. You have people who know the context and have it down very well, and then you have people who know the text and have it down very well. But the marriage of the two is much more powerful and effective in outreach to call people to Islam.

MM: Is that marriage of text and context what you’re trying to do for young people with the Mihraab Foundation?

SQH: Yeah. We’re trying to bring an element of cool and fun to religion. We keep it religious, we keep it halal, we keep it traditional, but we also want to make it fun and entertaining and beneficial.

The people who work and volunteer at Mihraab, most of us have been raised in America. Most of us have been born and raised in the West. We are the next generation. We are Americans. We are Westerners and we know this society and culture and we know what issues the youth are facing.

MM: What is your favorite part of serving the community?

SQH: That moment when you help change somebody’s life for the better. And not just this life, but their afterlife. When you really benefit someone, really help somebody, you can really see it on their face and see them change.

If you really care about somebody, you care about them in this life and in the next life. You care about their salvation and their survival. You care about their eternal abode. So those are things I try to help people with – not just this-life decisions but next-life decisions. It can be very stressful, very heavy. It’s a big responsibility.

MM: Is that the hardest part of what you do: the weight of that responsibility?

SQH: It’s partly that. I would also say being pulled in so many different directions is difficult. You get so many requests and you want to answer all of them, but you can’t. It’s hard to focus sometimes and find that balance between religion, work and family.

MM: Talk about your experience in Yemen and how you wound up there.

SQH: Yemen was a wonderful experience. As for the process of how I went there: I’d graduated from college and came to Spokane to live with my mother and stepfather. I was there for a year, working with my mother and stepfather, trying to practice (Islam) more.

One time I was sitting in a room by myself and said to Allah, “Allah, I know that you exist and I don’t doubt that. But show me a sign that you exist.” I said, “I commit myself, everything that I am, my health and my wealth, to you for your sake; just show me a sign that you exist.” Not that I doubted; I just wanted to be reassured. That night, Allah answered my prayer through this really powerful dream that shook and changed my life forever.

After I saw that dream, I started studying and reading the Quran more. I was reading books, watching videos about Islam, trying to learn Arabic, trying to memorize the Quran. Allah was guiding me in a certain direction. I started to ask about studying abroad to study Arabic and I looked into programs, and the one place that responded was a place in Tarim, Yemen, called the Badr Institute. (Author’s note: Tarim reportedly has the world’s highest concentration of descendants of the Prophet Muhammad

I went there initially to study Arabic for a year and come back, but I fell in love with the place, the people, the knowledge. I ended up staying year after year … each year was supposed to be my last year. Seven years later, I graduated with a license to teach. I came back to the United States in 2011 when I was 31 years old.

MM: When you study a religion as in-depth as you studied in Yemen and in the years since, do you come across things that may challenge your faith or that contradict what you believed going in?

SQH: When I ran into things like that, it only strengthened my faith. The reason why is because a lot of knowledge is in the people. It’s in the heart – from heart to heart, teacher to student, father to son, it’s passed down. Remember, Islam began as an oral tradition, not necessarily as a book. It starts with people.

The chain of transmission that goes back to the Prophet Muhammad is the proper way to understand Islam. You have to go back, as Allah says in the Quran: “So ask the people of knowledge if you do not know.” (16:43) When you come to things that may seem like contradictions or conflicts or something that doesn’t seem right, it’s very important to bring that back to the scholars who understand and who have that chain of transmission back to Prophet because they can help one understand and interpret it.

When things get taken out of context and out of the proper understanding of what was going on at that time, then somebody can misunderstand and misinterpret, and that can lead to an extreme version of religion. And we see that all over the world today. You have to read the texts and go back to the teachers. They’re professionals; they’re experts. They’ve been studying this since they were kids and now they’re old men. Like, day in and day out, it’s their full-time job. Where we suffer today in the world of Islam is we have people who have the text but not the context, or they have the context and no text. The combination of text and context is very important. That helped remove any contradictions for me.

MM: So when you arrived in the U.S. from Yemen, were you considered a scholar?

SQH: By American standards, yes. They say the one-eyed man is king in the land of the blind (laughs). In America, where we don’t know our religion and our knowledge is so little, yeah, I would’ve been considered a scholar. But by the standard of where I studied, I would be a student of a student of a student of a scholar. And these are giants – massive scholars. Here they’ll say “Shaykh Qasim” or refer to me as a scholar, but not how I see it.

MM: What did you do when you first came back to put that Islamic education to use?

SQH:It was really hard. People who come back like me, you have to be prepared to struggle. You have to understand you’ll start small and have to build up. It’s not a prestigious thing, what I do, in the Western world. We need imams, we need scholars and teachers, but it’s more lucrative to be a doctor or a computer programmer, you know? People value other jobs.

When I first came back, it was a major culture shock. Even though I was born and raised here, it was all different. Good was bad, bad was good, everything was flipped upside down and I didn’t know what to do.

I didn’t have anything. I was married. I was struggling to get a license again; I didn’t have a car, no house, no job, no money … we didn’t have anything. So when I came to Seattle, I stayed with my brother initially, and my wife moved to California to stay with her family for month and a half. I then moved into some brothers’ apartment and was sleeping on the floor, basically starting from scratch. It was cold. I was hungry a lot.

So, all I could do is what I came back to do: I started teaching a few kids, upstairs in the masjid. I wasn’t getting paid. I started with a very small group of kids, and then more and more kids came, and pretty soon adults started coming. The word spread and the community started to help and support; I was able to get a very humble salary and bring my wife back from California. Eventually we got low-income housing, got a halal loan for a car, and just slowly started to build.

MM: We’ve seen a few stories over the years of people like yourself who played big-time college sports and either had a chance to go pro or made it to the pros, but walked away voluntarily for religious or health reasons. The perception of those athletes seems to be that they fell out of love with their sport, or grew disillusioned with their sport, making it easier to leave. How do you feel about football today?

SQH: Football is a great sport. I still watch football. I still play football sometimes with the youth we work with. It’s kind of funny because they’ll be surprised when they find out Shaykh Qasim can actually throw a Hail Mary (laughs).

But at the end of the day, it’s just a game. It’s not worth losing one’s religion over and certainly not worth dying over. And I’ve had a couple of teammates die, actually; one from a broken neck and another from drugs. When you really break it down, you’re putting on armor and trying to prevent another man from crossing a line, or you’re hitting a ball between two posts. When you really break it down, it’s kind of silly and not important. But people love it and they’re big fans and want to watch, and that’s okay.

But putting it in perspective, I don’t think that on the Day of Judgment, Allah is going to ask me, “How many sacks did you have?” He’s gonna ask, “Who is your lord? What is your religion? Who is your prophet?” Those are the questions I want to be able to answer in my grave. I want to be able to enter paradise through what I do in this life. That’s what’s important to me. It’s about working and striving for the next life, not necessarily playing a game in this life.

MM: What was so attractive about the athlete lifestyle before you changed your mindset?

SQH: Like any kid at that time, I wanted to play in the NFL and be famous and make a million dollars and be on TV, stuff like that. I loved the team, the brotherhood. But that brotherhood is temporal.

Football is a business and the athletes are commodities. They want you to gain weight, lose weight, be faster or be stronger so they can win more games and make more money. It’s a business. And as soon as you’re not playing or not winning games, that brotherhood disappears. But the brotherhood of Islam remains forever.

MM: How did you fit into that brotherhood since you identified as a Muslim?

SQH: At first it came with a lot of curiosity. “Why won’t you take showers with everyone else in the locker room?”

“Why don’t you have a girlfriend?” “Why don’t you drink with us at the parties?”

They were wondering why I was doing certain things, and I would tell them it’s because I’m Muslim. When that came up, then it’s like, “Oh, you’re different. You’re not like us.”

There’s pressure to conform and assimilate to the American ways or ideals of football culture. And this was pre-9/11, but it was still socially acceptable to make fun of, criticize and stereotype Muslims. I mean, everything under the sun … I was called a terrorist, a camel jockey, a towel-head. Whatever derogatory name that could describe a Muslim, I heard it from my own teammates.

I could relate more with the African-American players because we were both minorities and we understood that racism and bigotry. A lot of the bullying, stereotyping, hazing, intimidation, prejudice … a lot of it came from the white half of the team. When I was being hazed as a freshman, I had to stand on a chair and sing, “Oh, thank heaven for 7-11” over and over again. Because, you know, you’re Muslim so you must own a gas station. And that was okay. It was done in front of coaches, in front of staff, everybody.

So I got that for a while before I earned my stripes. Then when I started to play, I got more respect. When I became a starter, the remarks and comments went down, because it was like, “Oh, now we actually need him.” Then, that love occurs.

MM: Did any teammates come to you interested in learning more about Islam or in converting?

SQH: Some were curious, like, they just want to know more about you and your background and what you believe. There were some that were probably genuinely interested in Islam. Being that it is the fastest-growing religion in the world and it’s the truth, a lot of people are attracted to it. And once they meet a Muslim and see they’re not like what they see on TV, it draws them to it. The resilience, the faith, the steadfastness of Muslims – it either bothers people or it attracts them.

MM: Did you ever feel conflicted playing football while practicing a religion that teaches peace?

SQH: It was hard for me because that’s not how I was raised and not what I was taught. I was taught to be non-violent, and then football is probably the most violent sport I’ve ever experienced in my life. They say you’re protected because you have pads, but the pads just allow you to hit harder, faster and stronger and potentially cause more damage because you’re hitting over and over and over again. Most players finish their careers and have severe injuries that affect them the rest of their lives. They’ve put more miles on their bodies and advanced their age 10, 20 years because of football. It’s a violent game, and not only are you doing it, but it’s being done to you.

They say they don’t want you to hurt anybody, but actually a lot of the coaches directly or indirectly suggest that you do hurt the opposing player and take them out of the game, because ultimately the goal is to win the game.

What it all boils down to is not even winning games, but making money. Football is a meat market. It’s a business. It’s about money, and a lot of money. And the way that they make money is by winning games. So they’ll do what they can to win games to reach their ultimate goal of making money, and as an athlete you’re the product. You’re the commodity. You can be bought, you can be sold, you can be traded … Obviously, college football players get a free education, but it’s a full-time job.

So there is element of encouraging athletes to be violent. Football is organized chaos. It’s legal war on a field. To say it’s just a game and there are no consequences is false. You’re trying to take out the other guy, he’s trying to take you out, and there are consequences. The ultimate was in 2000, when we played Stanford. I was right next to an athlete, Curtis Williams, No. 25, and I went one way while he want the other way. I probably should have hit the fullback, but he ended up hitting the fullback in a head-on collision. His head was low and he broke his neck. I saw him on the field. We thought he was dead because he’d stopped breathing. About a minute or two later he came back to life and started breathing again, but he was still unconscious. He was a quadriplegic for two years, had kidney failure and died. And what was it that resulted in his death? A football game.

MM: How is your health now?

SQH: Alhamdulillah, I’m getting older (laughs). I have some knee problems and back problems, but my health is good now.

I actually had a reoccurrence of the blood clots 10 years later (in 2011). This one was from a long flight from Yemen to the U.S. I had another three clots – not as large as the first ones. The first ones, I waited until the last possible moment. This time I saw the signs earlier. So to this day I’m cautious of blood-clot issues.

It’s very different when you’re practicing Islam and trying to follow the will of Allah and you see the bigger picture. The first time, I was so attached to the life of this world that I couldn’t let it go. It was so hard for me to think about letting it go. This time, I was like, “Whatever Allah wills.”

MM: Why focus your work on the youth?

SQH: Probably the two most neglected groups among Muslims are the youth and converts. They need the most help.

There’s a major disconnect between the first generation and the second generation, between immigrant parents and their children. There are a lot of immigrants in Seattle; it’s an immigrant community. And they’re having kids and they think their kids are being raised like they were back home, but they’re raising them in America now. Their kids are showing one face to them but another face to their friends or to their community. There’s a huge disconnect and a huge generational gap. We’re trying to bridge that gap and also be supporters for the youth.

We are losing more [youth] than we’re retaining. A lot of them are going astray and leaving the practice of Islam altogether and doing some pretty crazy things. Some of them have almost a dual personality; they show their parents one thing, show the people at the masjid one thing, but when they’re in the club or in school or at work, they’re a whole different person. It makes them not sure who they are, so there’s an identity crisis. We’re trying to show people that you can be Muslim and American — Muslim first, but also American as long as it’s halal.

There has to be a group of people who were born and raised in America, Islamically educated and practicing, who can take them by the hand and guide them through the ropes. Instruct them; be a role model; be an example; show them how to weave through the wild waters of how to be good Muslims and also be an American.

One of the mottos of our program is, “Come as you are, to Islam as it is.” We’re not going to change. Islam is what it is, but come as you are and you’ll be accepted.

MM: What role can sports play in making that outreach to the youth and strengthening their deen?

SQH: Sports is a huge way to attract the youth. They already don’t have as many options compared to non-Muslims. And if we don’t make the halal accessible to the youth, they will go after the haram. If we make it difficult for them to do halal things like sports, video games, fishing, hiking, then they’ll go after haram things that are easy and accessible for them. And we know how rampant that is in our society.

It’s very important just to bring them in – that’s why we call it the filter. We attract the biggest amount we can through the big filter. It’s through sports a lot of times because that’s what they like, that’s what they play, that’s what’s fun and that’s what’s halal. But then we filter that into, “OK, this is how we’re going to practice Islam. These are the etiquettes and manners. This is how a Muslim should be.” We can play sports and have fun, but now let me show you how to do wudu and how to fast and how to pray.

MM: Can sports help develop some of the morals and values you’re trying to impart?

SQH: Sports is about team building, teamwork, social bonding. You see character come out in sports. You see personalities of individuals come out. You learn work ethic, how to work together. There are good morals one can learn from sports.

There are some good things about sports, but there are also some bad things. I probably wouldn’t want my own children playing sports on the collegiate or pro level because the norm is that they’ll get lost in it. I’ve seen that from Muslims. There are exceptions, but not everybody is the exception.

When we do youth camps we have football, soccer, volleyball, inner tubing, fishing … we have S’mores and campfire talks and we discuss things as Muslim-American citizens. We try to make them feel comfortable while guiding them through challenges. We do all of that stuff, and we also have deen sessions. We talk about service, we talk about leadership, we talk about brotherhood, we talk about loving each other and respecting one another. It’s a very powerful model.

If you can combine fun, religion and social bonding, that seems to be a very powerful combination to attract those youth who are never going to just come to the masjid or never go to an Islamic conference. They might be on-the-fence Muslims, but they’ll go to a basketball game. They’ll join us there and meet some brothers, bond with them, there may be a brotherhood established where they want to spend more time with us. OK, now there’s a connection. So hey, let’s go have some halal food. Then, hey, let’s go to the masjid and pray. So now a kid who was just tagging along for the sports is now praying in the masjid. And I’ve seen this lead to them coming more and more often.

We had one kid who was on the streets selling drugs. He came to one youth halaqa, he liked it, so he came again. And he kept coming, because we’re talking about real issues. Whether it’s drugs, whether it’s gender relations, whether it’s drinking or parties, whether it’s peer pressure, we’re talking about real things … and we’re talking about Islam too.

Now that kid wears a thobe and a kufi when he comes to the masjid and prays.

[divider]—————————————[/divider]

Follow Sh. Qasim Hatem on Twitter: @QasimHatem

Visit the Mihraab Foundation: http://www.mihraab.com/

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Amaar Abdul-Nasir was born and raised in Seattle, Wash., and received his B.A. in Journalism from Seattle University. A sports writer and editor by trade, Amaar founded UmmahSports.net, which focuses on Muslim athletes and health and fitness in the Muslim community, following his conversion to Islam in 2013.

Week 1 in Review: Is Your Teen Actually Changing? | Night 7 with the Qur’an

NICOTINE – A Ramadan Story [Part 1] : With A Name Like Marijuana

Why Your Teen Wants to Change Their Muslim Name | Night 6 with the Qur’an

[Film Review] Time Hoppers: The Silk Road

The Comparison Trap | Night 5 with the Qur’an

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

[Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy

[Podcast] Guardians of the Tradition: Muslim Women & Islamic Education | Anse Tamara Gray

Op-Ed: Bitterness Prolonged – A Short History Of The Somaliland Dispute

Week 1 in Review: Is Your Teen Actually Changing? | Night 7 with the Qur’an

Why Your Teen Wants to Change Their Muslim Name | Night 6 with the Qur’an

The Comparison Trap | Night 5 with the Qur’an

When You’re the Only Muslim in the Room | Night 4 with the Qur’an

When Honoring Parents Feels Like Erasing Yourself | Night 3 with the Qur’an

MuslimMatters NewsLetter in Your Inbox

Sign up below to get started

Trending

-

#Current Affairs1 month ago

[Podcast] Should Muslims Ally with Conservatives or Progressives? | Imam Dawud Walid

-

#Islam1 week ago

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

-

#Current Affairs1 month ago

Op-Ed: From Pakistan To Gaza – Why Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan Terrifies Power And Zionism

-

#Islam4 weeks ago

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

Umm Hadi

December 20, 2014 at 12:03 PM

Masha Allah, Takabbal Allahu minna wa minkum.

https://alkalaamblog.wordpress.com/

dude bro

December 22, 2014 at 3:54 AM

Very touching article mashaAllah, extremely inspiring. This mindset should be the paradigm of everyone looking to, or involved in community work. May Allah preserve Him and bless his work and make countless more like him around the world. Ameen.

Razan

December 24, 2014 at 7:00 PM

This is honestly pretty damn amazing. Thanks for sharing your story – in my family we would say ‘qaddaralllahu wa ma sha’a fa3al’ – God willed, and what He wills is done.

john

September 27, 2016 at 2:42 PM

subhanallah i love this story..unbelivable

Ahmed Brown

December 24, 2014 at 11:36 PM

A wonderful and poignant story. Thanks sh. Qasim for sharing, Amaar for writing, and MM for publishing!

mufti ishaq

September 28, 2016 at 6:01 PM

i love the shieks beautiful talks.

sheik google

September 29, 2016 at 2:53 PM

i as sheik google approve this story..its true