#Culture

Op-Ed: Bitterness Prolonged – A Short History Of The Somaliland Dispute

Published

By

Ibrahim Moiz

A longstanding aspirant statelet in the Horn of Africa shot to international attention this month when Israel announced its recognition of Somaliland, an otherwise unrecognized defacto state in northern Somalia that has existed since war engulfed the region in the 1990s. Because the issue of Somaliland secession is widely unknown to Muslims outside the region, this article will give a short summary of its history.

Colonial Contrasts

Somalis constitute one of East Africa’s major ethnic groups, organized in clans and clan confederations and tracing their history back centuries in the region: major clan confederations included the Isaq, who dwell largely in Somaliland, the Hawiye in central Somalia around Mogadishu, the Rahanweyn in western Somalia, and the Darod, scattered around the region.

Today, Somalis are split across several countries beyond the eponymous Somalia. In part, this is a legacy of colonialism, when the British, French, and Italian empires waded into the Horn of Africa, where Somali clans and sultanates had already had a long history of opposition with Ethiopia. Djibouti became a French enclave; Somaliland and Kenya were British colonies; and the rest of Somalia was under Italian rule, with the exception of the Ogadenia region, named for the Ogaden clan within the Darod confederation that predominates in a region ruled by Ethiopia as its southeast province.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Italy’s defeat in the Second World War bequeathed most of Somalia to British rule, where it remained for a decade before official independence in 1960. The first British thrust into the region, some fifty years earlier, had been countered by the daring preacher and adventurer Mohamed Hassan, disparaged as the “Mad Mulla” for his twenty-year resistance. Hassan, from the Darod, had a mutual enmity with the Isaq confederation, which, unlike most others, Somalis do not remember him fondly. Somaliland had been a British colony for much longer than the rest of Somalia, and in fact was given independence a few days earlier in the summer of 1960.

Somalilweyn and its Discontents

That independence came after a long period of activism from Somali opposition parties, notably the Somali Youth League, which called for Somali independence and where support for the independence of the Somali peoples at large, not just those under British rule, was widespread in what became known as Somaliweyn or Greater Somalia.

A key roadblock to this idea was not just friction with neighbouring powers, notably an imperial Ethiopia whose rule of Ogadenia was widely unpopular, but also the balance of power within Somalia itself. Somaliland had become independent under its leading colonial politician, Ibrahim Egal, who was soon persuaded to join the rest of Somalia, for which he became prime minister. As a rule, Somaliland was a backwater, and much of the Isaq populace chafed; as early as 1961, there was a coup attempt that was speedily suppressed. In fact, as one of the few parliamentary democracies in 1960s Africa, Somalia’s first decade was generally marked by chaotic factionalism and in 1969 army commander Siad Barre led a coup; prime minister Egal, at the United States at the time, was imprisoned on his return as one of the many elites of his generation purged by the military regime.

Though Siad promised revolutionary change, siding at first with the Soviet Union in the Cold War against a Western-backed Ethiopia; what socioeconomic improvements he oversaw would be drowned by his own recourse to repression and corruption. A change in family law that contravened Islamic law in 1975 was an early flashpoint, and after a momentous war for Ogadenia in 1977-78 failed – where Somalia’s former Soviet allies switched sides to decisively join a newly communist Ethiopia – Siad’s dictatorship began to crumble from within. An early sign of the rupture came when Majerteen officers from Siad’s Darod confederation, led by Abdullahi Yusuf, attempted a coup immediately after the Ogadenia defeat; in its wake, Yusuf fled to Ethiopia, which supported him in a 1982 incursion into Somalia.

Corrosion under Siad

The 1982 campaign came even as Siad repressed another coup and purged his Isaq deputy, Ismail Abukar. Though Abukar was one of a number of cross-clan leaders imprisoned in this period, the Isaq clan in particular objected to Siad’s dictatorship; the previous year, a rebel Somali National Movement or Wadaniya had been founded by exiles in Britain. Though its membership was overwhelmingly Isaq – including former officials such as Ahmed Silanyo, police officers such as Jama Ghalib, army officers such as Abdulqadir Kosar, and clan leaders such as Yusuf Madar – the group importantly claimed to represent Somalia at large and, unlike its heirs today, rejected claims of secession.

Siad, by now bolstered with considerable weaponry by the United States, responded with an outsize cruelty that overwhelmingly targeted Isaq in the north and drove more into the insurgency’s ranks. By the late 1980s, an insurgency was in full swing and had overrun much of Somaliland. In response, in spring 1988, Siad’s son-in-law, Said Morgan, cut a deal with the Ethiopian regime to stop supporting one another’s insurgents before turning on Somaliland with savage ferocity.

The Harrowing of the North

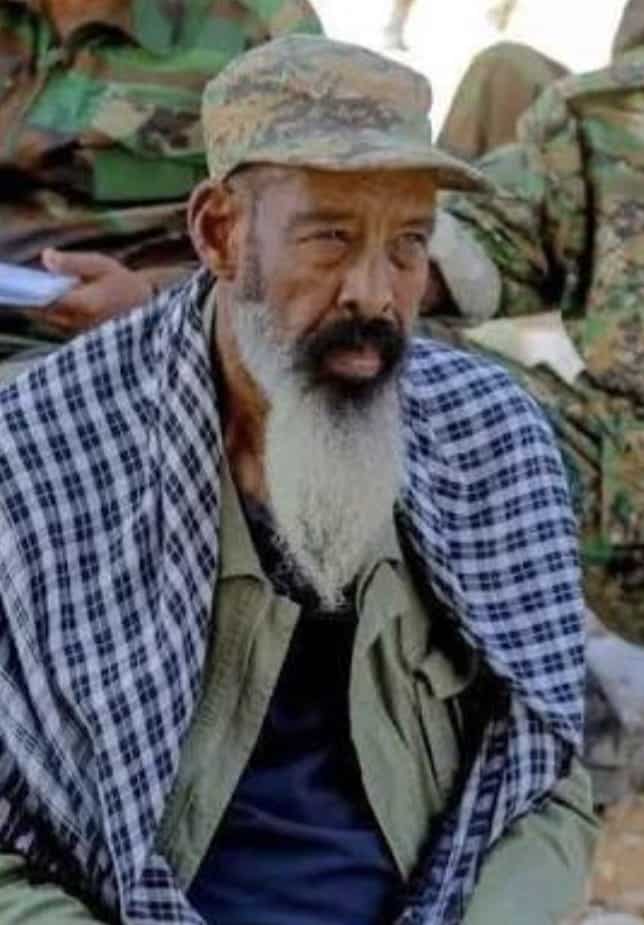

Said Morgan, the “Butcher of Hargeysa”

Morgan’s destruction of Somaliland carries parallels with the Iraqi Baath regime’s meantime harrowing of its own, Kurdish northland, during the same period. Like the Baath’s murderous governor-general, “Chemical” Ali Majid did with the Iraqi Kurds, there is no doubt that Morgan and his lieutenants saw Isaq as a fifth column to be bloodily crushed. As with supposed voice recordings of “Chemical Ali”, there are letters supposedly from Morgan that call for the elimination of the Isaq confederation; whether or not these are genuine, there is no question, and ample reliable evidence, that Morgan and his lieutenants were willing to butcher the population in droves. One particularly infamous call by an officer was to “kill everything but the crows” that came to feast on corpses. In the process, Morgan flattened Hargeysa and killed thousands, particularly through aerial bombardment.

As did Iraqi Kurdish opponents of the Baath regime, Siad’s opponents characterize this massacre as a genocide of the Isaq. It did, however, occur among a general narrowing of the regime where Siad, despite his rhetoric of shunning clan prejudice, narrowed his group of loyalists to not only his clan but his own family; it is no coincidence that his son-in-law, Morgan and son, Maslah Barre, were increasingly prominent in the army. The Isaq clan were the most brutalized but by no means the only victims; Siad had already frozen out the Majerteen clan within his own Darod confederation, and his favouritism also alienated much of the Darod’s Ogaden clan, whose army officers increasingly defected. Similarly, the major Hawiye confederation predominant in Mogadishu was increasingly disconsolate. By the early 1990s, a mixture of revolts and mutinies ousted Siad and helped plunge Somalia into what was unprecedentedly described as a “failed state”.

Freedom and Independence?

In the process, the Wadaniya insurgents managed to capture Somaliland under the leadership of Abdirahman Tur; along with the Isaq confederation, the Darod Dhulbahante clan, led by such cooperative chieftains as Abdulghani Jama, now joined them. Wadaniya was more of a coalition than a fixed group, however, and its constituent camps began to fight for power. That this struggle was not as destructive as that of the remaining Somalia owed largely to the mediating role of chieftains and elders, who organized a number of conferences and elections.

Isaq chieftains such as Ibrahim Madar, son of the former Wadaniya leader Yusuf, were especially important and, with the rest of Somalia in disarray, began to push increasingly for secession. Somaliland was already de facto separate from the rest of Somalia, but the persistent agenda from the mid-1990s onward was for its recognition as a separate country. Since Somaliweyn had collapsed and Somalis were already split between other countries like Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Kenya, the argument ran, there was no point in Somaliland staying in a dysfunctional Somalia either. The moment also seemed propitious; in 1993, Eritrea broke away from Ethiopia after a long, difficult independence war.

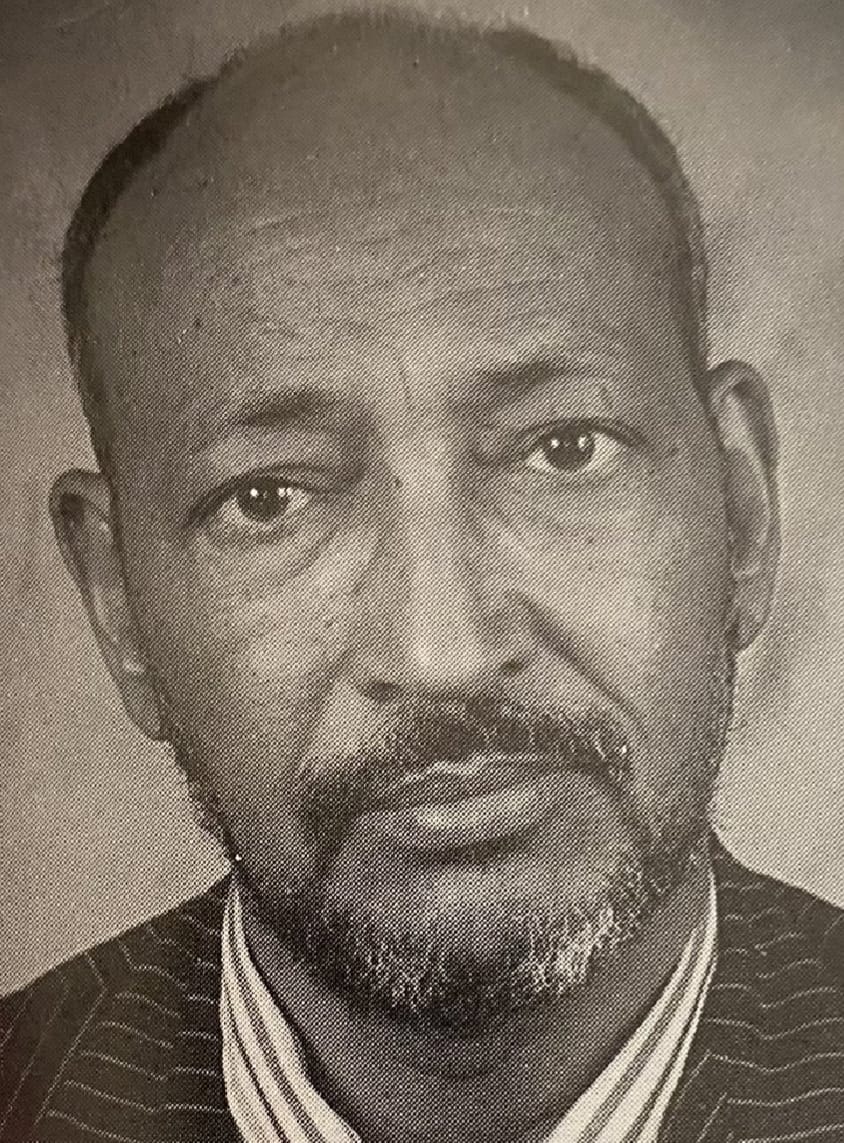

Jama Ghalib

Even as the United States was leading a United Nations incursion into the rest of Somalia, Tur was removed in favour of the former Somalia prime minister Egal. Isaq commanders Tur and Ghalib, a former police inspector-general, opposed the secessionists and joined forces with Farah Aidid, Mogadishu’s preeminent commander who had first ousted Siad, and then the United States. However, in 1994-95, Somaliland “loyalists” of Egal managed to bloodily root out these Isaq dissidents in a series of battles at Hargeysa and Burao.

As a former prime minister of Mogadishu who had originally negotiated Somaliland’s addition to Somalia, Egal struggled to convince hardline separatists of his bona fides. Yet as his power increased, sidelining competitors by the late 1990s, he did indeed press toward a separatist agenda, and was even reported to have contacted the infamously anti-Muslim Israeli regime by offering cooperation against “Islamic radicalism”: this despite the fact that the original Wadaniya resistance against Siad had criticized his irreligiosity and dealt heavily in Islamic slogans, styling themselves “mujahids”; indeed, the Somaliland flag retains the Islamic shahadah. Somaliland was nonetheless seen favourably among foreigners wary of the conflict in remaining Somalia, and a considerable foreign lobby grew for its separation from Somalia and its recognition as an independent state. A year before his death in 2002, Egal held a referendum that opted for Somaliland’s secession as an independent state.

Somaliland, Puntland, and the Occupation of Somalia

However, secessionism was unpopular among the Dhulbahante who predominated in the Sool region of northern Somalia, between Somaliland and the coastal region of Puntland. Many Dhulbahante dissidents gravitated east toward Puntland, where Ethiopia’s former vassal Yusuf, had set up his own fiefdom and aimed to form Puntland as part of a federalist but united Somalia. When the American “war on terror” began, Puntland, and Yusuf more specifically, became a favoured client of the United States as a “counterterrorism” partner. In 2006, both the United States and Ethiopia invaded Somalia and ousted Mogadishu’s short-lived Islamist government, installing Yusuf in its place under a foreign occupation.

Yusuf’s place at the helm of an American-Ethiopian-backed regime in Mogadishu ensured that Puntland had Washington’s ear, but Somaliland’s major foreign lobby persistently argued for independence, while periodically cracking down against dissidents who favoured a united Somalia. The fact that the original 1980s Wadaniya resistance had rejected separatism was now conveniently forgotten; the fact that unionist Somalilanders such as Ghalib opposed the 2006 invasion ensured that they could be frozen out of the political elite with little repercussions.

On the other hand, even after Yusuf’s resignation, the Somali government and its Puntland wing attracted largely Dhulbahante dissidents in Sool who wanted their region to be separate from Somaliland and part of Somalia, either as part of Puntland or as a separate region. During the 2010s, when Somalia’s new federalist constitution was arranging new regions, the Sool region pressed its case: led by Ahmed Karash, the Sool region announced its loyalty to Somalia under the name “Khatumo” or finality, with support from both the central government in Mogadishu and the regional government in Puntland. There have been repeated clashes over this region, particularly Lasanod, since 2007.

Regional Rivalries

The replacement of relatively conciliatory Somaliland leaders such as Silanyo with hardline separatists like Musa Bihi, a former Wadaniya commander, helped harden this dispute. So did the attitudes of strongly unionist Somali leaders such as Mohamed Farmajo, who ruled Mogadishu in 2017-22, and Puntland leaders such as Said Deni, who was a rival to both Mogadishu and Hargeysa.

Regional rivalries also played into these disputes. A staunch centralist, Farmajo was long backed by Turkiye and Qatar, and opposed the United Arab Emirates, which was supporting a number of separatist actors in the region. He also tried to cultivate better ties with the new, similarly centralist Ethiopian ruler Abiy Ahmed. Ethiopia, which had a longstanding rivalry with Cairo, had meanwhile long found it convenient to play off the rivalry between Puntland and Somaliland, and the United States did the same. Saudi Arabia initially supported the United Arab Emirates in its dispute with Qatar, but has recently moved closer to Ankara, Cairo, and Doha.

The Somali government’s case was widely recognized abroad, but its own legitimacy was weakened by its reliance on the multipronged foreign occupation that had ousted the Islamists in 2006. Although a compromise brought back many Islamists, including the ousted former ruler Sharif Ahmed and his successor Hassan Mohamud, to the fold in 2009, cyclical squabbles over the makeup of the state and over an unpopular but essential foreign occupation have persisted. At their most extreme, Somali unionists resorted to the untrue claim that Shabaab, the main insurgent group, was a Somaliland agent, because many of its leaders were Isaq northerners. This was fantasy, but the claim’s very existence pointed to the difficulty of legitimation during a foreign occupation.

Road to Disgrace

After returning to power to remove Farmajo, Mohamud managed to secure Lasanod and announced the new Sool-Khatumo region as a separate region, under Abdulqadir Firdhiye. However, Puntland leader Deni, closely affiliated with Abu Dhabi, threatened secession in 2024. And at the end of 2025, Israel, closely linked by now with the United Arab Emirates, followed up its support for secessionists in other Muslim countries by recognizing Somaliland.

In a move whose criticism within Somaliland was swiftly suppressed, Somaliland leader Abdirahman Irro welcomed Israeli foreign minister Gideon Saar and oversaw a generally shameless spree of welcomes for this new, supposedly groundbreaking relationship. Like other pro-Israel governments in the Muslim world, Hargeysa evidently supposes that ties to Israel will strengthen its international position, particularly with the United States. It is a disgraceful denouement to a political experiment that began with genuinely valid grievances but has morphed into an autocratically ruled fiefdom.

The fact is that the Somalia regime that ravaged Somaliland in the 1980s ceased to exist decades ago, and that the current Somaliland programme bears little resemblance to the Wadaniya insurgency of that period. Even as its government loudly cites the savagery of a long-extinct dictatorship in the 1980s to justify its separatism, Somaliland cracks down on dissidents and aligns itself with the most vicious regime of the 2020s.

[Disclaimer: this article reflects the views of the author, and not necessarily those of MuslimMatters; a non-profit organization that welcomes editorials with diverse political perspectives.]

Related:

– History of the Bosnia War [Part 1] – Thirty Years After Srebrenica

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Ibrahim Moiz is a student of international relations and history. He received his undergraduate degree at the University of Toronto where he also conducted research on conflict in Afghanistan and Pakistan. He has written for both academia and media on politics and political actors in the Muslim world.

Op-Ed: Bitterness Prolonged – A Short History Of The Somaliland Dispute

Far Away [Part 6] – Dragon Surveys His Domain

Green March In The Sands Of The Blue Sultan: Morocco And The Conflict Over The Western Sahara

What Shaykh Muhammad Al Shareef Taught Us About Making Dua

[Podcast] Should Muslims Ally with Conservatives or Progressives? | Imam Dawud Walid

Faith and Algorithms: From an Ethical Framework for Islamic AI to Practical Application

Quebec Introduces Bill To Ban Prayer Rooms On College Campuses

An Iqbalian Critique Of Muslim Politics Of Power: What Allamah Muhammad Iqbal’s Writings Teach Us About Political Change

MM Wrapped – Our Readers’ Choice Most Popular Articles From 2025

Muslim Book Awards 2025: Finalists

[Dhul Hijjah Series] Calling Upon the Divine: The Art of Du’a (Part 1)

IOK Ramadan 2025: Four Steps | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Do Your Best | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Giving Preference to Others | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Which Group Are We In? | Sh Zaid Khan

Trending

-

#Islam1 month ago

Restoring Balance In An Individualized Society: The Islamic Perspective on Parent-Child Relationships

-

#Life4 weeks ago

Faith and Algorithms: From an Ethical Framework for Islamic AI to Practical Application

-

#Islam1 month ago

The Limits Of Obedience In Marriage: A Hanafi Legal Perspective

-

#Culture1 month ago

Far Away [Part 1] – Five Animals