#Current Affairs

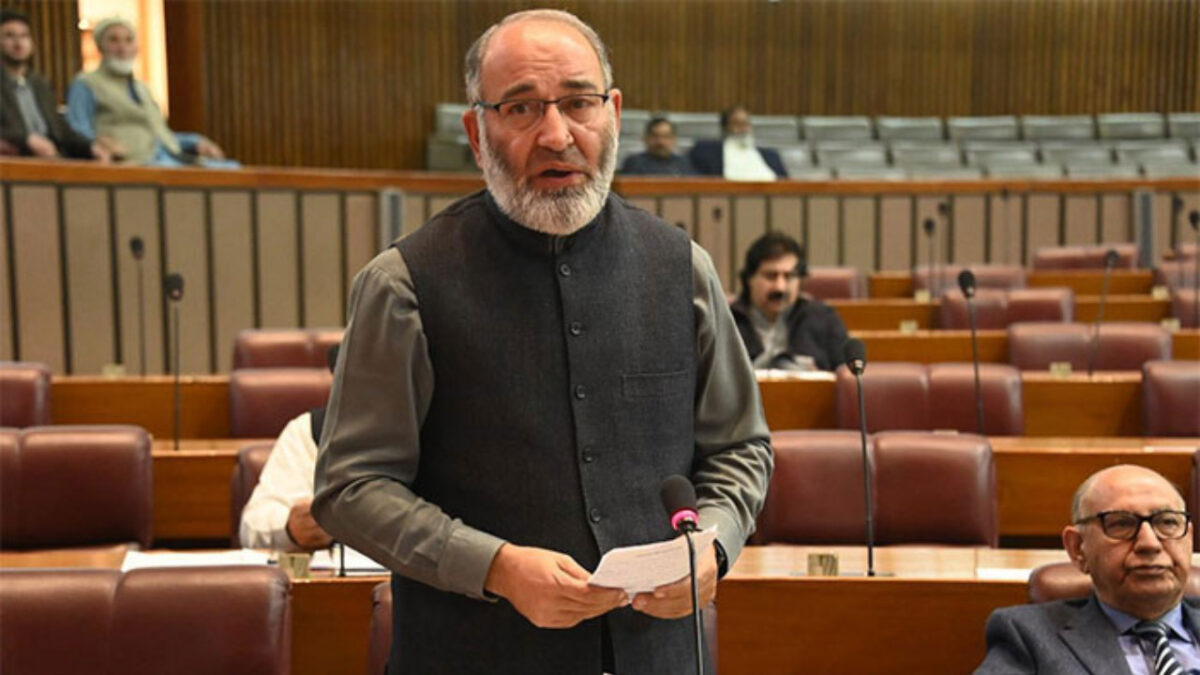

Op-Ed: From Pakistan To Gaza – Why Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan Terrifies Power And Zionism

Published

Every dictatorship eventually collides with a problem it cannot solve by expanding prisons, perfecting surveillance, or laundering repression through emergency laws. That problem is conscience. Not the decorative conscience wheeled out in constitutional preambles or Friday sermons, but the dangerous, embodied kind: people who insist on calling crimes by their proper names, who refuse to perfume mass violence with the language of “security” or “complexity,” and who behave — almost scandalously — as if power were still accountable to principle.

Pakistan’s rulers understand this problem well. They have built an entire governing philosophy around neutralizing it.

In Pakistan today, Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan occupies precisely this intolerable space. He does not command mobs. He does not control institutions. He does not benefit from the romantic mythology reserved for martyrs or political prisoners. What he possesses instead is far more destabilizing to a regime addicted to fear and confusion: moral coherence. He behaves as if ethical clarity were not a public-relations liability to be managed but a responsibility to be exercised.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

That posture — quiet, disciplined, unyielding — explains why he matters. It also explains why he is dangerous.

Moral Presence in an Age of Managed Brutality

Authoritarian systems are, above all, management projects. Pakistan is no exception. It manages narratives, crises, alliances, dissent, and public memory with the meticulousness of a corporate risk department. What it cannot manage — what consistently escapes its spreadsheets and talking points — is moral presence.

Moral presence is disruptive because it refuses translation. It refuses to convert injustice into “context,” mass killing into “geopolitics,” or repression into “stability.” It insists that some acts are wrong regardless of who commits them, how eloquently they are justified, or how many uniforms are involved.

Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan’s politics operate in this register. His participation in the Gaza solidarity flotilla was not a publicity stunt or an exercise in symbolic humanitarianism. It was a direct refusal to outsource solidarity to press releases. At a moment when Muslim rulers perfected the art of condemning genocide in the passive voice — where Palestinians are always “dying” but never being killed — he chose presence over prose.

He crossed a line Pakistan’s generals, bureaucrats, and their Western patrons desperately prefer remain blurred: the line between rhetorical sympathy and embodied accountability.

That decision reverberated far beyond Gaza. It landed squarely in Islamabad and Rawalpindi, and in the quiet calculations of a regime that understands — perhaps better than its critics — how contagious moral consistency can be.

Two Consciences, Two Cells

Pakistan’s current moment is defined by a grim symmetry. Its two most morally resonant political figures now occupy opposite sides of a prison wall.

Imran Khan, jailed, censored, and methodically erased from public life, embodies the conscience of mass politics: the inconvenient truth that popular legitimacy cannot be indefinitely manufactured, managed, or extinguished. Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan, still free for now, embodies something the regime finds equally threatening: proof that ethical clarity does not require state power, mass rallies, or electoral machinery.

The regime grasps this distinction instinctively. Mass leaders can be isolated, demonized, or imprisoned. Moral leaders are harder to neutralize. They do not rely on crowds or cycles. Their authority travels horizontally, through example rather than command. It accumulates quietly, beneath the regime’s noise, until it becomes impossible to contain.

This is why Senator Mushtaq’s activism has sharpened rather than softened. Through the Pak-Palestine Forum and the Peoples Rights Movement, he has rejected the regime’s preferred compartmentalization — one in which Palestine is mourned abstractly while Pakistan is governed brutally, one in which foreign oppression is lamented while domestic repression is normalized.

He insists, instead, on linkage. That insistence is unforgivable.

The Crime of Consistency

Dictatorships do not fear hypocrisy. They depend on it. Hypocrisy is the lubricating oil for authoritarian rule. What they cannot tolerate is consistency.

“Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan’s politics operate in this register. His participation in the Gaza solidarity flotilla was not a publicity stunt or an exercise in symbolic humanitarianism. It was a direct refusal to outsource solidarity to press releases.” [PC: @SenatorMushtaq, US Social Media Company X]

This is what unites the figures Pakistan’s current rulers find most intolerable.

Barrister Shahzad Akbar’s insistence that law should function as principle rather than weapon cost him safety and exile. Imaan Mazari’s defiance — amplified rather than tempered by her mother, Dr. Shireen Mazari — ruptures the convenient fiction that human rights must be suspended in imperfect governments. Dr. Mazari’s tenure as minister for human rights is dismissed not because it failed, but because acknowledging it would complicate the intellectual laziness of liberal gatekeepers.

Dr. Yasmin Rashid’s endurance, Ammar Ali Jan’s principled radicalism, and the courage of Baloch and Pashtun leaders resisting erasure under conditions bordering on colonial occupation all represent variations of the same threat: they refuse to turn politics into branding. They insist on substance where power prefers symbolism.

The regime’s response is uniform: criminalization, vilification, disappearance. Consistency is met with coercion because it cannot be bargained with.

The Unnamed Majority and the Regime’s Real Fear

To focus only on prominent figures, however, is to miss how resistance actually survives.

Dictatorships are not undone by heroes. They are undone by accumulation — by the steady aggregation of small refusals. A taxi driver who speaks honestly despite surveillance. A teacher who refuses to recite official lies. A lawyer who takes a case she knows she will lose. A journalist who documents one more testimony before the knock comes.

These people will never be celebrated. That is precisely why they terrify power.

Authoritarianism survives by convincing people that their courage is singular. Fear isolates. It interrupts accumulation. It persuades individuals that resistance is futile when, in fact, it is shared.

Pakistan’s rulers invest obsessively in fear because they understand this arithmetic.

Palestine as a Moral X-Ray

Linking Palestine to Pakistan’s internal crisis is not a rhetorical excess. It is an analytical necessity.

Palestine functions as a moral X-ray of the contemporary world order. It reveals how easily states abandon principle when convenience beckons. It exposes the vocabulary through which mass murder is sanitized — “security,” “self-defense,” “rules-based order” — how those same vocabularies migrate seamlessly into domestic repression.

Zionism, as practiced by the Israeli state, is not an aberration. It is a concentrated expression of a global logic that treats some lives as disposable and others as strategically valuable. The same logic that justifies the annihilation of Gaza authorizes the pacification of dissent in Pakistan.

When Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan speaks against apartheid-genocidal Israel, he is not performing internationalism. He is diagnosing a system. That diagnosis unnerves Pakistan’s rulers because it collapses the distance they rely on. It reveals that the victims of empire recognize one another — even when their oppressors coordinate discreetly.

The Regime’s Dilemma

Pakistan’s rulers depend on fragmentation — between causes, movements, and moral vocabularies. They prefer activists who choose single issues and avoid dangerous connections. They are deeply threatened by figures who connect dots.

Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan does exactly that. He refuses to choose between Palestine and Pakistan, between anti-Zionism and anti-dictatorship, between faith-based ethics and universal human dignity. He insists these struggles are not adjacent but inseparable.

That insistence is his protection and his peril.

For now, he remains outside prison. History suggests this is rarely permanent.

The Final Accounting

A reckoning will come. Prisons will open. Files will be read. Silence will be reclassified as collaboration.

When that day arrives, many will rediscover their principles retroactively. Some will plead ignorance. Others will invoke “complexity.” A few will insist they were merely pragmatic.

Very few will be able to say they spoke plainly when plain speech carried a cost.

Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan will be among them.

So will the thousands whose names will never appear in essays like this.

Dictatorships do not fall because they are exposed. They fall because they are exhausted by the relentless refusal of ordinary people to surrender their moral vocabulary.

That refusal is Pakistan’s most valuable resource.

And it remains — despite everything — uncaptured.

[Disclaimer: this article reflects the views of the author, and not necessarily those of MuslimMatters; a non-profit organization that welcomes editorials with diverse political perspectives.]

Related:

– Allies In War, Enemies In Peace: The Unraveling Of Pakistan–Taliban Relations

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Prof. Junaid S. Ahmad has a Juris Doctor (law) degree from the College of William and Mary, USA. He is the Director of the Center for the Study of Islam and Decolonization in Islamabad, Pakistan. He has been teaching Law, Religion, and Global Politics for over a decade in Pakistan, South Africa, Malaysia, Turkey, the UK, and the USA. He does a wide array of consultancy on issues related to international law and international affairs. Junaid is also the founder and Chair of the Palestine Solidarity Committee (PSC) - Pakistan. Over the years, he has been associated with the International Movement for a Just World (JUST), the Center for Islam and Global Affairs (CIGA), Al-Awda (The Palestine Right to Return Coalition), along with various interfaith initiatives and groups working for peace and justice - including Peace for Life (PFL) and the US-Pakistan Interreligious Coalition (UPIC). Most recently, he co-founded JUST-IS, a global network advancing interfaith solidarity against militarism, and is also a part of the Palestine solidarity group, Movement for Liberation from Nakba (MLN). He served as president of the US-based National Muslim Law Students Association (NMLSA), and is a member of the American Academy of Religion (AAR), the Middle East Studies Association (MESA), the American Sociological Association (ASA), the Association of Muslim Social Scientists (AMSS), the National Association of Muslim Lawyers (NAML), the South Asian Muslim Studies Association (SAMSA), and the American Council of the Study of Islamic Societies (ACSIS). His research interests include US foreign policy, the Middle East and South Asia, global geopolitics, international law, globalization, and critical issues in the contemporary Muslim World.

Op-Ed: From Pakistan To Gaza – Why Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan Terrifies Power And Zionism

The Sandwich Carers: Navigating The Islamic Obligation Of Eldercare

Far Away [Part 4] – A Safe Place

Why I Can’t Leave Surah Al-Mulk Hanging Every Night

The Muslim Book Awards 2025 Winners

Restoring Balance In An Individualized Society: The Islamic Perspective on Parent-Child Relationships

Ahmed Al-Ahmed And The Meaning Of Courage

Faith and Algorithms: From an Ethical Framework for Islamic AI to Practical Application

Far Away [Part 1] – Five Animals

The Limits Of Obedience In Marriage: A Hanafi Legal Perspective

[Dhul Hijjah Series] Calling Upon the Divine: The Art of Du’a (Part 1)

IOK Ramadan 2025: Four Steps | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Do Your Best | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Giving Preference to Others | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Which Group Are We In? | Sh Zaid Khan

MuslimMatters NewsLetter in Your Inbox

Sign up below to get started

Trending

-

#Islam3 weeks ago

Restoring Balance In An Individualized Society: The Islamic Perspective on Parent-Child Relationships

-

#Current Affairs4 weeks ago

Ahmed Al-Ahmed And The Meaning Of Courage

-

#Life1 month ago

AI And The Dajjal Consciousness: Why We Need To Value Authentic Islamic Knowledge In An Age Of Convincing Deception

-

#Culture1 month ago

Moonshot [Part 32] – FINAL CHAPTER: A Man On A Mission