#Culture

Nationalism And Its Kurdish Discontents [Part I of II]: Kurds In An Ottoman Dusk

Published

By

Ibrahim Moiz

This spring, Turkiye’s AK government, led by Tayyip Erdogan, secured what promises to be a momentous agreement with the longstanding Kurdish insurgent group, the Parti Karkeran Kurdistan (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) led by Abdullah Ocalan, which has waged an insurgency against the Turkish state for the better part of four decades. This comes a hundred years since the first Kurdish revolt against the Turkish Republic, the 1925 revolt led by the Naqshbandi sheikh Mehmed Said against the republic’s founder, Kemal Atatürk. This first of two articles on the Kurds in Turkiye will examine the background of Kurdish activism during the final years of the Ottoman sultanate.

Background

As a multiethnic Islamic sultanate, Ottoman rule from Istanbul was systematically undermined by the nineteenth-century emergence of nationalism, which both undercut Islamic universalism and provoked unrest among the sultanate’s Christian minorities, often with support from rival European powers such as Britain and Russia. As a European import, nationalism had a limited appeal until Istanbul’s own attempts at centralizing administrative reforms, which often met a sharp backlash outside the corridors of power. As fellow Muslims who had enjoyed a considerable degree of autonomy under traditional leaders such as chieftains and preachers, few Kurds welcomed Ottoman centralism and a number of major families, notably the Bedirkhans (Badr Khans) of Bohtan, resisted these measures, as well as sociopolitical upheaval caused in the borderlands with Russia and Qajar-ruled Persia. In 1880-81, the Nehri Naqshbandi preacher Ubaidullah Khalidi b. Taha led a major attack on Iran, and only relented under the pressure of Ottoman sultan Abdulhamid II before briefly challenging the Ottomans in turn.

Ubaidullah’s dissatisfaction with Ottoman and Qajar rule, as well as his insistence on an autonomous if not independent Kurdish frontier, has made him renowned as a proto-nationalist. He adopted a stance that would be echoed in many future Kurdish leaders, including his son Seyid Abdulkadir: official loyalty to the government, but parallel negotiations with foreign powers with a view to securing autonomy from centralism. In fact, the vast majority of Ottoman Kurds remained loyal to the government, and Abdulhamid increasingly armed them under the command of Millan chieftain Ibrahim Milli to fight Armenian nationalists backed by Russia during a bloody, undeclared war at the turn of the century. Stressing his title as caliph, Abdulhamid was nonetheless widely resented by a wide number of people, particularly the intelligentsia, by this point: his secretive, wary rule during a period of decline was increasingly resented and when he was ousted in the so-called Young Turk coup of 1908, traditional Kurdish leaders were among the few who rallied to his cause. Millan chieftain Ibrahim in Syria and the Barzinjis Saeed and his son Mahmoud in Iraq launched brief and unsuccessful revolts against the new regime.

Homogenization

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

The Young Turk coup, which brought together a mishmash of ideological and political trends united only by their desire for change, promised a more representative government, but in fact, proved far more repressive than its predecessors. Though a number of the Young Turks were Kurds, and though such Kurdish notables as Seyid Abdulkadir were given senior positions, in fact power soon came to rest with a militaristic clique that, in the “civilized” fashion of the day, viewed Ottoman heterogeneity as a potential weakness and increasingly sought not only centralizing but also culturally homogenizing practices, with the particular promotion of Turkish identity often at the expense of other identities.

Notable Kurdish families and leaders, including the Bedirkhans, Babans, and the Cemilpasazades (Jamil Pashazadas), were forced to operate underground. Others, such as the Barzanis, who had a record of rather heterodox religious activity but enjoyed a widespread following in what is now northern Iraq, briefly rebelled. Several Kurdish clans broke off their relations with the Ottomans; when, during the Balkan War of 1912-13, Istanbul came under threat, one chieftain, Abdulkadir Dirai of the Karakecili, expected that the Ottomans would fall and rebelled, only to be imprisoned once they survived. Other Kurdish clans remained loyal to the sultanate and were often employed against their local rivals.

Ibrahim Milli [PC: haberercis.com.tr]

Throughout the devastating First World War that followed, Kurds fought in huge numbers for the Ottoman state: as many as three hundred thousand Kurds lost their lives in the Ottoman cause, and major units in the eastern frontline against Russia were largely Kurdish. The war saw communal displacement and upheaval on an unprecedented level, and not simply by the Ottomans’ enemies: though Russian-backed Armenian nationalists had been extremely brutal against Muslim civilians, the Ottoman state responded with a wholesale assault on the Armenian populace at large, which was massacred and systematically displaced. This was to date the worst assault of any Muslim government against a dhimmi minority; it was also a precursor to ideas of homogenization that would emerge after the war.

During the war, a handful of Kurdish notables, including Abdulkadir’s nephew Seyid Taha of Nehri and some of the Bedirkhans, openly colluded with Russia as it briefly captured the borderland. This availed them little as Russia soon collapsed, but was less momentous than the role of Arab counterparts -again, against the vast majority of loyalist Arabs- who helped Britain advance in Arabia and the Levant. Eventually, the Ottomans were forced to sue for peace in the autumn of 1918, whereupon their remaining opponents -France, Britain, and Greece, with a smattering of Italian and Armenian nationalist forces- occupied Istanbul and the surrounding countryside. The recently installed Ottoman sultan, Vahdettin Mehmed VI, sought to cut his losses, purge the Young Turks, and enter a disadvantageous peace with the victors: he hoped that a shared dislike of the Young Turks, who had brought the sultanate to ruin, would enable the European victors to view him with sympathy, but they instead aimed to split the Ottoman heartland between them. In this context, Kurdish nationalists, led by an Ottoman Kurdish general called Mehmed Serif (Muhammad Sharif), also sought the establishment of an independent Kurdistan.

Resistance and Collaboration

By contrast, other Kurds, as well as Turks and Arabs, fought this occupation of Muslim territory. In Anatolia’s heartland, they were led by a number of renegade Ottoman generals: Kemal Atatürk, Kazim Karabekir, Ibrahim Refet (Bele), Fuat Cebesoy, and Vahdettin’s former negotiator, Huseyin Rauf (Orbay). Although the palace treated them as rebels, they insisted that they were liberating the sultan from foreign subjugation, and their argument was given strength by the European powers’ uncompromising stance toward Istanbul. They employed Islamic arguments of jihad that intermixed with already existing resistance elsewhere, both in Anatolia as well as Iraq and Syria, and these at least originally united many Kurds with Arabs and Turks.

Though the sultan and Atatürk reached an uneasy agreement by the end of 1919, in spring 1920 Britain sabotaged this with a full-scale crackdown in Istanbul. This forced the remaining parliament to flee to Ankara, where Atatürk set up a “shadow government”. The last humiliation for the sultanate came in the Sèvres Accord: though Vahdettin had hoped that he could salvage a good deal through cooperation with the occupation, in fact, the European powers decided to split up his lands and thus lent credence to the Ankara-based parliament’s call for a jihad. Although the Accord rewarded Mehmed Serif’s lobbying with a vague reference to Kurdistan, in actual fact this came after a year of fierce fighting between Britain and large parts of the Ottoman Kurdish population.

Kurdish participants in resistance included several Kurdish chieftains: Ali Bati of the Haverkan clan, Abdurrahman Aga of the Shernakhlis, and Ramadan Aga of the Salahan. Similarly, Karakecili chieftain Abdulkadir Dirai and Millan chieftain Ibrahim’s son Mahmud were released from prison to lead Kurdish forces. But the political uncertainty and ambiguous jurisdiction of the period, and suspicion and rivalries among the participants often clouded events. For instance, when Bati captured Nusaibin in May 1919, the army led by Kenan Dalbasar wrongly suspected him of French-backed subversion and drove him out, where he was killed. Similarly, when Istanbul sent a governor, Ali Galip, to arrest Atatürk that autumn, he was accused of being in league with French-backed Kurdish secessionists, causing the palace huge embarrassment. Finally, in early 1921, a particularly ruthless Turkish general, Nurettin Konyar, uprooted a largely Alevi Kurdish revolt by the Kocgiri clan in eastern Anatolia, with a ferocity that alarmed even his colleagues in the resistance. This revolt had demonstrable links to the British occupation and to Serif’s secessionists, thus cementing a suspicion of Kurdish agitation that was to resurface again.

In fact, Kurdish collaboration with Britain was the exception to the rule. Resistance was especially fierce in British-occupied Iraq, in whose north Ottoman veterans such as the Young Turks’ former defence minister Ismail Enver encouraged Kurdish revolt among historically rivalled clans such as the Zebaris, the Barzanis, and the Surchis. Participants included Mala Mustafa of Barzan, Karim Fattah of Hamawand, Faris Agha of Zebar, Mahmoud Dizli of Hawraman, Nuri Bawil of the Surchis, Abbas Mahmoud of Pizhdar, and Mahmoud Barzinji. Their local rivals backed Britain, along with opportunists such as Seyid Taha as well as chieftain Ismail Simko of the Shikak clan, a marauding freebooter on the Turco-Persian borderland who had once fought for the Ottomans but often changed sides.

Sheikh Mahmud Barzanji (Kurdish: Mahmud Barzinji (1878 – October 9, 1956) was the leader of a series of Kurdish uprisings against the British Mandate of Iraq. He was sheikh of a Qadiriyah Sufi family of the Barzanji clan from the city of Sulaymaniyah, which is now in Iraqi Kurdistan. He was styled King of Kurdistan during several of these uprisings. [PC: Alamy Stock Photo]

In summer 1922, Ankara dispatched Sefik Ozdemir (Shafiq Ozdamir), the descendant of a notable Mamluk family who had most recently fought France and, during the World War, encouraged a shared Muslim opposition to the European foe. Far more than other Turkish officers, Sefik won the trust of Kurdish clansmen, supporting Karim and Abbas in battle against the British occupation. Unable to trust the weak Taha or the adventuresome Simko, Britain turned instead to Mahmoud Barzinji, who promised to repel the resistance if they let him rule Sulaimania. Once installed there, however, he made contact with Sefik and joined the revolt to announce himself shah of Kurdistan.

It was not until 1923 that this joint Turkish-Kurdish resistance was defeated. Though Mahmoud Barzinji was expelled from Sulaimania, British rule in the Kurdish region was extremely tenuous, and he was able to return repeatedly over the next few years. In order to beat him and other Iraqi opponents, Britain relied on massive aerial bombardment, a novel technology a the time that wrought havoc on the Kurdish countryside in a process that would be repeated by one government or another against Kurdish rebels over the next century.

[…to be contd.]

Related:

– The Role Of Kurds In The Dissemination Of Islamic Knowledge In The Malay Archipelago

– Calamity In Kashgar [Part I]: The 1931-34 Muslim Revolt And The Fall Of East Turkistan

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Ibrahim Moiz is a student of international relations and history. He received his undergraduate degree at the University of Toronto where he also conducted research on conflict in Afghanistan and Pakistan. He has written for both academia and media on politics and political actors in the Muslim world.

Far Away [Part 8] – Refugees At The Gate

[Podcast] Guardians of the Tradition: Muslim Women & Islamic Education | Anse Tamara Gray

Digital Intimacy: AI Companionship And The Erosion Of Authentic Suhba

Starting Shaban, Train Yourself To Head Into Ramadan Without Malice

Far Away [Part 7] – Divine Wisdom

Op-Ed: From Pakistan To Gaza – Why Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan Terrifies Power And Zionism

[Podcast] Should Muslims Ally with Conservatives or Progressives? | Imam Dawud Walid

The Sandwich Carers: Navigating The Islamic Obligation Of Eldercare

Keeping The Faith After Loss: How To Save A Grieving Heart

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

[Podcast] Guardians of the Tradition: Muslim Women & Islamic Education | Anse Tamara Gray

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

[Dhul Hijjah Series] Calling Upon the Divine: The Art of Du’a (Part 1)

IOK Ramadan 2025: Four Steps | Sh Zaid Khan

IOK Ramadan 2025: Do Your Best | Sh Zaid Khan

Trending

-

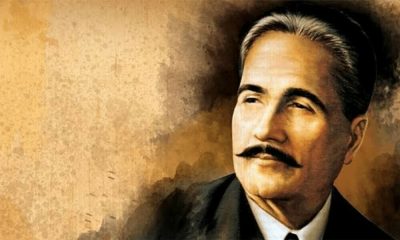

#Current Affairs1 month ago

An Iqbalian Critique Of Muslim Politics Of Power: What Allamah Muhammad Iqbal’s Writings Teach Us About Political Change

-

#Culture1 month ago

MM Wrapped – Our Readers’ Choice Most Popular Articles From 2025

-

#Current Affairs4 weeks ago

Op-Ed: From Pakistan To Gaza – Why Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan Terrifies Power And Zionism

-

#Culture1 month ago

The Muslim Book Awards 2025 Winners