#Culture

Calamity In Kashgar [Part I]: The 1931-34 Muslim Revolt And The Fall Of East Turkistan

Published

By

Ibrahim Moiz

[Note: This article makes some use of the administrative term “Xinjiang”, not in recognition of China’s claimed sovereignty but as an administrative description for a sprawling region. Uyghur activists often refer to this region as East Turkistan, a quite fair claim that this usage is in no way intended to contest: for purely descriptive purposes, the term Xinjiang is used when referring to China’s administrative structure]

The increasing plight of Muslims and in particular Turkic minorities under China’s rule in its sprawling western Xinjiang province has attracted considerable attention in recent years. The Uyghur Turkic group native to the region for centuries has in particular come under mass surveillance in eerily misnamed “reeducation camps”, supposedly to drain them of religious fanaticism. Because the region was historically linked to Turkic Central Asia rather than China, successive Beijing governments have treated it as a special problem since conquering the region in the late eighteenth century, with a long record of Muslim revolt. This article will look at the first Uyghur-led “state”, the short-lived East Turkistan Republic that was founded in what is now southern Xinjiang by Turkic militants in the 1930s; a follow-up article will examine its successor in the 1940s.

Background

The 1930s were a period of major upheaval in Asia primarily by non-Muslim empires: the sprawling totalitarian behemoth of the Soviet Union to the north wiping out the last vestiges of Muslim resistance in Central Asia, the British Empire in the south staving off both political and armed opposition, and a horrendous civil war in China featuring a murderous Japanese invasion to the east. Since the 1910s, Beijing had exercised little control over Xinjiang, its largest but also sparsest western province, and effectively outsourced its authority to whatever militia was most powerful. The pattern was particularly intensified in the sprawling western region called “Xinjiang”, or new conquest, which had been conquered from local Turkic principalities centuries earlier. This pattern continued after the Guomindang nationalists, led by Chiang Kai-Shek with considerable American support, took control of most of China: embroiled in a vicious war with the communists led by Mao Zedong, they had little control over the governor-general of Xinjiang, a figure who often sought to expand his autonomy by getting help from the Soviets next door.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

The eastern Turkic lands were a striking region, with towering mountains, shimmering lakes, and sweeping deserts that drew the fascination of onlookers, with both Turk and Han referring to them by such names as “God’s heavenly mountains” or “God’s heavenly lakes”. Historically Uyghurs and other Turkic groups had long religious, political, and cultural links with Muslim emirates in Central Asia that trumped a faraway Beijing; nineteenth-century Muslim revolts in the region, for example, were supported by Central Asian emirates. But apart from Afghanistan, these emirates had largely been wiped out by the Russian behemoth after the First World War. As elsewhere in the late colonial world, the oppressive atmosphere of the day, with brutal and capricious military leaders ruling in China’s name, helped provoke various types of opposition – including Islamic, nationalist, and even socialist – in the region. The Jadidi trend, which called for a modern reassertion of Islam, was influential here, as it was throughout Turkic Asia. Apart from political trends, there were other galvanizing circumstances: Han officials stationed in the region, often for years at a time, frequently attempted to force unIslamic marriages with local women, one long-running source of friction between Beijing and the Turks of the West.

Ironically, however, one of the most important regional forces was a conglomeration of Muslim military adventurers of ethnic Hui background, the so-called “Ma clique” – so-called because Ma, the Han word for horse, was also used for Muhammad: they shared ethnicity with Beijing and religion with the Turks, but their principal leaders were also unpredictable military adventurers much like non-Muslim militia leaders, and though they opposed anti-Islamic policies by Beijing they were essentially attached to China, favoring reform and autonomy toward its Muslims rather than independence. Dynamics from war to the west, where the Soviets were mopping off Central Asian resistance, and China’s civil war to the east also spilled over into Xinjiang. This mixture of civil war, ambitious militias, and ethnic polarization formed a febrile tinderbox that would explode during the 1930s.

Roots of Revolt

In 1930 Xinjiang’s governor-general Jin Shuren annexed the historically autonomous Turkic khanate at the Kumul oasis. However, he gave its chamberlain Yulbars Khan a token position as a strictly circumscribed governor. Instead, Yulbars and a preacher called Niaz Alam secretly fomented a revolt that burst aflame after a local sheriff’s abuses in the spring of 1931. The revolt, which featured a massacre of ethnic Han, was met with a brutal response by Shuren’s troops, with major massacres against Muslims. Desperate for aid, the Kumul revolt enlisted an ambitious young Hui commander called Buying Zhongying, with a chancy reputation even among military leaders: his uncles in the Ma clique had expelled him from their stronghold in northern China. On the advice of Kemal Kaya, an Ottoman veteran on staff, Zhongying announced his intention for jihad and thundered into the oasis. A panicking Shuren was forced to frogmarch Russian exiles, many of whom lived in Xinjiang and had military experience, to Kumul. After defeating Zhongying in the autumn, they ravaged the oasis’ Muslims in a series of massacres.

Niaz and Yulbars now turned west, where a community of Kirghiz cavalry led by Eid Mirab had been uprooted by Soviet expansion and raided across the border. While in the summer of 1932 Shuren and the Soviets busied themselves with warding the Kirghiz off, Zhongying sent his lieutenant Ma Shiming to the Turkic south of Khotan, where unrest against government oppression was boiling over. In the autumn of 1932 a massive revolt broke out through the province – involving Muslims across ethnic lines from intellectuals and workers to military adventurers. In the northern Altai region, a Kirghiz militia led by Usman Ali defected to help a respected Kazakh leader, Sharif Khan, in revolt. In the southwest, Hui commanders Mas Fuming and Zhancang defected and turned their towns over. While Fuming and Shiming set off for Xinjiang’s capital Urumqi, Zhancang allied with a Uyghur adventurer called Timur Shah who had links to underground activists. Khotan was captured by Jadidi-influenced Bughra brothers Abdullah, Amin, and Nur Ahmedjan, who worked with a respected preacher called Abdulbaqi Sabit. This group had the most well-developed program of an aspirant Muslim Turkic emirate and influenced Uyghur miners’ revolts in the vicinity.

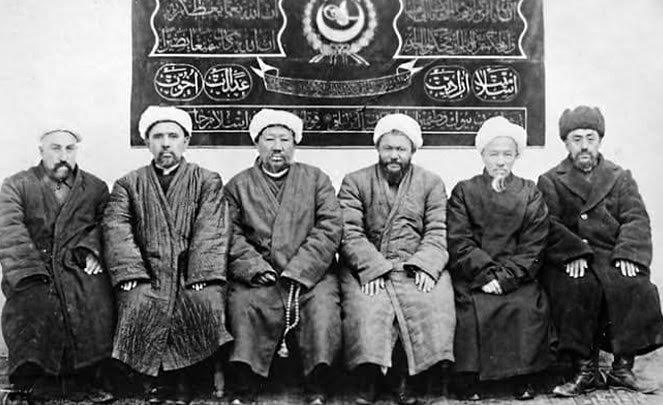

Leaders of the first East Turkistan emirate: premier Abdulbaqi Sabit, seated third from right, was martyred in a public execution in 1934. [Source: Haber Nida]

Mexican Standoff at Kashgar

But by now ethnic and political mistrust was creeping into the Muslim coalition. This owed in part to disparate aims – by and large, the Hui wanted Muslim rights but no more, but the Turks and especially Uyghurs called for independence – and in part to indiscipline. For example, when the Bughra brothers captured Yarkend they offered its garrison safe passage to Kashgar – where, instead, Usman’s disorderly Kirghiz militia slaughtered them. Suspicious of Turkic intentions, Zhancang secretly cut a deal with the regime’s Hui commander of Kashgar, Ma Shaowu. The Hui commanders suspected that the Turkic “rebels” and Han “regime” were secretly collaborating to cut them out. A major factor in this impression was the conduct of Niaz Alam, the Uyghur titular leader of the revolt, who unexpectedly attacked Ma Shiming in the north. In addition, Uyghur commander Ismail Baig expelled Zhancang’s Hui troops from Aksu.

But though Zhancang may have interpreted this as Turkic treachery, there was no grand conspiracy. Niaz Alam was secretly negotiating with Sheng Shicai and the Soviets, but Hui commander Buying Zhongying himself – theoretically the leader of the Hui forces in Xinjiang – was himself secretly negotiating with both the Guomindang and the Soviets, hoping to trump Shicai. It was, in short, a situation where nobody trusted the other, and the atmosphere was tautest at Kashgar. There was similarly major mistrust among the Turks: Uyghur commander Timur mistrusted Niaz, and he did not fully trust the Bughras, dispatching his lieutenant Hafiz Baig to “help” them capture Yarkend, where instead Hafiz competed with them for control of the attacking force. Timur invited Abdullah Bughra and Abdulbaqi Sabit to Kashgar, and when they arrived he imprisoned them. Kirghiz commander Usman was meanwhile urging him to attack Zhancang; fatefully, Timur instead turned on Usman’s unruly militia, and Zhancang snatched the opportunity to kill him. Taking advantage of the kerfuffle, Abdullah and Sabit escaped to take control of Yarkend; in their wake, Zhancang had affixed Timur’s decapitated head to a pike in front of Kashgar’s main mosque.

In November 1933 the Bughras and Sabit returned to Khotan, where amid much fanfare they announced an independent East Turkistan Republic, with a strong dosage of both Islamic and Turkic themes as well as the distinctive pale-blue flag that Uyghurs retain today. Sabit was officially its prime minister, but the East Turkistanis made a major mistake in choosing Niaz Alam, who at the time was still secretly negotiating his share of power with the Soviets and Beijing, as its emir, but who was advocated by a mysterious Arabian arrival from Syria, a certain Sayed Taufiq.

Abdullah Bughra, one of the three Bughra brothers who led the first East Turkistan emirate and was martyred in 1934. [Source: “Uyghur Collective”]

The Muslim coalition had shattered. Niaz’s treachery now came out into the open, and he abandoned the East Turkistan movement in return for a promotion to Shicai’s deputy. On the other side Niaz’s saviour-turned-rival Zhongying brutally stamped his control of the south: Sabit was executed along with his lieutenant Sharif Qari, while two Bughra brothers, Abdullah and Nur Ahmedjan, were killed in a brave last stand at Kashgar. The third brother, Amin, managed to escape Khotan with three thousand followers for Ladakh. In midsummer 1934 Zhongying left his brother-in-law Ma Hushan to rule the south, while in the north Kazakh defections helped the Soviets defeat his lieutenant Ma Heying. Apparently in search of bigger prizes, Zhongying himself went in petition to the Soviet Union, where he disappeared forever; it is often speculated that he joined the Soviet military. It could, alternatively, be that the Soviets weren’t Buying his latest defection, and that this unpredictable adventurer ended his life as one of Stalin’s countless victims.

A Brief Burst

Sheng Shicai had no intention of giving the Muslims of Xinjiang, whom he mistrusted, much leeway. Though he had retained some Hui commanders and also won over a number of Turkic lieutenants from the original 1931 revolt – including Niaz Alam, Yulbars Khan, and a popular commander called Mahmud Muhiti – he soon began to purge them. This was a period where imperial Japan had invaded China’s east, and Shicai supported both of the Japanese empire’s opponents, the governments of China and the Soviet Union. In imitation of the Soviets, he mounted a vicious crackdown on both Muslims, including many purged officials, and, increasingly, Islam itself by the late 1930s.

Shicai’s provocations had indeed provoked Muslim unrest, both among the citizenry and the elites. Ironically it was the Hui commander Ma Hushan, whose notorious cruelty toward Uyghurs in his southern fiefdom had provoked a brief uprising in 1935, who was openly plotting a Muslim revolt against Shicai and hoping to get Japanese support. Separately, Amin Bughra and Sayed Taufiq asked for Afghan and Japanese support in a Muslim revolt, with the aim of installing Muhiti at the helm of a Muslim state.

Muhiti’s cover was blown in the spring of 1937, and he escaped across the border into India. In his wake Muslim soldiers led by Kichik Akhund and Abdullah Niaz captured Yarkend and advanced on Kashgar, capturing its old city to great celebration as the garrison withdrew. Reinforcements sent by Shicai, including Pai Zuli and the Hui Mas Julung and Shengkui, instead defected, and by summer the Hui commanders had taken over the Kashgar front, with Shicai’s garrison confined to the citadel while the city was under Muslim control. Once more it seemed that the Muslims were about to capture the Kashgar region, and once more the panicking governor-general called in Soviet help. A major expedition of five thousand Soviet soldiers, supported by airpower, stormed across the border. Seeing which way the wind was blowing, Ma Shengkui switched sides again and attacked the Muslims at Kashgar, both Turks and Hui. The Muslims were pursued south across the border, fleeing into India; most of the leaders escaped, but Abdullah Niaz was captured in battle at Yarkend and executed. For the second time within a decade, an imminent Muslim win had been denied.

Conclusions and Lessons

The first East Turkistan government had lasted a single season, from November 1933 to spring 1934. Channeling considerable, justified Muslim resentment against the governor-general in Xinjiang, Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples had made a coalition with the powerful Hui militia that promised not only to retake the historic Turkic south – what was referred to as “East Turkistan” – but also Altai, Kumul, and Urumqi in the north of Xinjiang. Ultimately, however, the Muslim coalition foundered upon the disparate aspirations of its leaders, with the Uyghurs favoring independence while the Hui favored autonomy, and a pervasive atmosphere of mistrust fed by incredibly cynical self-interest. Few groups in the war – whether Han, Hui, Kirghiz, or Uyghur – were free of atrocity, and each group featured such a diversity of ambitious characters that coordination became impossible. The original aim of throwing off an oppressive yoke was lost in the fray.

The second revolt, in 1937, seemed to have learned some lessons and was generally less fractious. Once again, however, Soviet muscle and a key defection thwarted its aims, so that it was routed even faster. It was not until the 1940s, at the height of the Second World War, that a Muslim revolt would make itself felt again. On that occasion, ironically, it would be supported by the same Soviets that had twice cheated it in the 1930s.

[…contd. in Part II]

Related:

– Islam In Nigeria [Part I]: A History

– From Algeria to Palestine: Commemorating Eighty Years Of Resistance And International Solidarity

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Ibrahim Moiz is a student of international relations and history. He received his undergraduate degree at the University of Toronto where he also conducted research on conflict in Afghanistan and Pakistan. He has written for both academia and media on politics and political actors in the Muslim world.

Cultivating A Lifelong Habit Of Dua In Children

When to Walk Away from Toxic Friends | Night 9 with the Qur’an

My First Ramadan As A Convert: The Lengths Small Acts of Kindness Can Go

What Islam Actually Says About NonMuslim Friends | Night 8 with the Qur’an

Ramadan, Disability, And Emergency Preparedness: How The Month Of Mercy Can Prepare Us Before Communal Calamity

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

[Podcast] Guardians of the Tradition: Muslim Women & Islamic Education | Anse Tamara Gray

Who Am I Really? What Surat Al-‘Asr Teaches Muslim Teens About Identity | Night 1 with the Qur’an

Starting Shaban, Train Yourself To Head Into Ramadan Without Malice

When to Walk Away from Toxic Friends | Night 9 with the Qur’an

What Islam Actually Says About NonMuslim Friends | Night 8 with the Qur’an

Week 1 in Review: Is Your Teen Actually Changing? | Night 7 with the Qur’an

Why Your Teen Wants to Change Their Muslim Name | Night 6 with the Qur’an

The Comparison Trap | Night 5 with the Qur’an

Trending

-

#Islam1 week ago

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

-

#Current Affairs1 month ago

[Podcast] Should Muslims Ally with Conservatives or Progressives? | Imam Dawud Walid

-

#Islam4 weeks ago

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

-

#Life1 month ago

[Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy