#Current Affairs

Israeli Assault On Lebanon Kills Hassan Nasrullah: A Look Back On The Politics That Shaped His Leadership

Published

By

Ibrahim Moiz

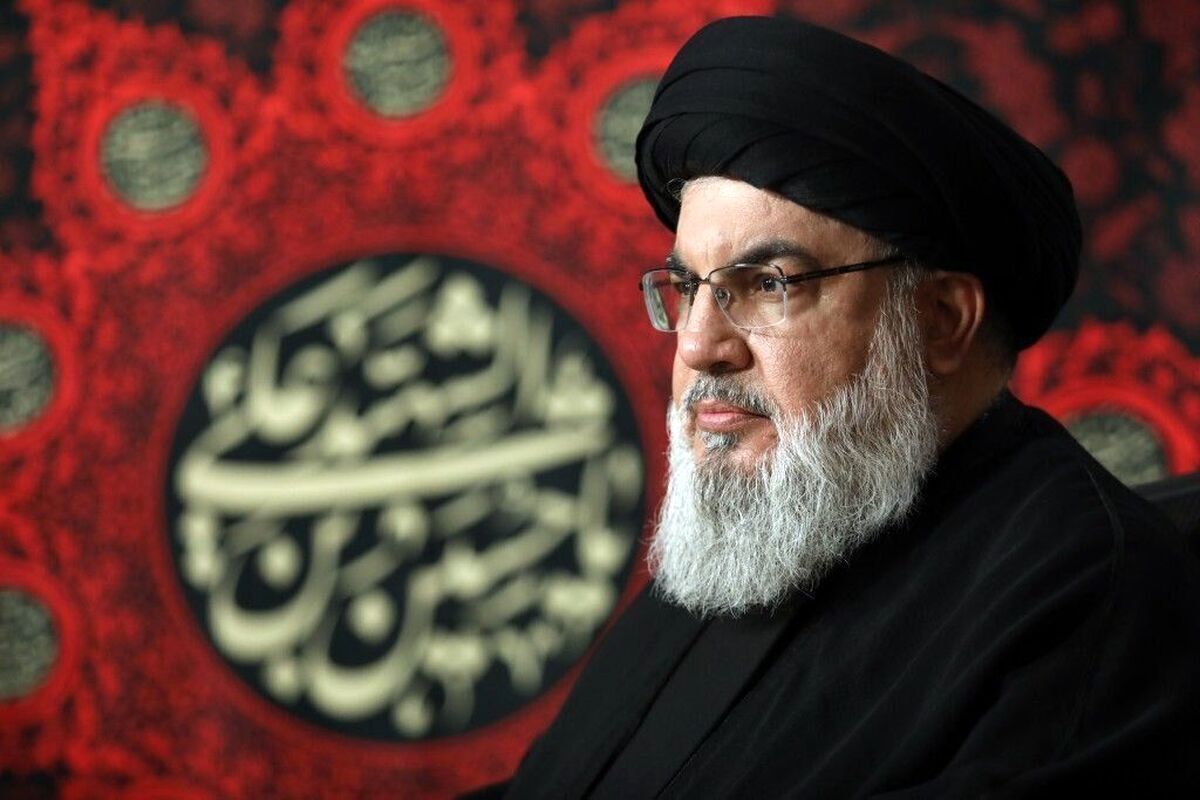

The news filtered slowly through the smoke and ashes of the wreckage in Beirut after a gigantic Israeli bombardment: Hassan Nasrullah, the longstanding leader of Lebanon’s most formidable militia, had been slain. The group that he had led for over thirty years, which styled itself Hezbollah – or God’s Party – took a while to confirm the Israeli kill, which put paid to one of the Levant’s most consequential political-military leaders in recent history.

Not only had Nasrullah led Lebanon’s largest, best-equipped, and best-drilled militia – indeed, the only one that had survived decades of war in the late twentieth century with major strength – Hezbollah is also a major jewel in the crown of Iran’s regional vassals. The group’s popularity, which abides among Lebanon’s Shia population in particular, was once shared throughout the region as a result of its impressive military record against a bullying Israel’s repeated incursions into Lebanon.

Under Nasrullah’s leadership, Hezbollah challenged, and eventually forced to a close, Israel’s eighteen-year occupation of southern Lebanon in a way that no Arab force had done so before. That it was able to do so rested both in its roots among the long-disenfranchised and recently militant Shias of southern Lebanon – roots that included not only military but political, cultural, social, and economic dimensions – and also its particularly close links with Tehran. As by far the group’s longest-lasting and most charismatic leader, Nasrullah epitomized his group’s link with an Iran that bolstered and emboldened, but ultimately failed, to protect him.

Background

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Lebanon’s Shias had historically had a marginal role in Lebanese society and politics, confined largely to the southern peasantry presided over by a handful of aristocrats. In the 1970s this changed with the rise of populist politics that was most effectively harnessed by a populist cleric trained in Iran, Moussa Sadr. Raised in poverty like thousands of other Lebanese Shia, Hassan Nasrullah was attracted to Sadr’s Amal Movement, and is said to have been gravely informed by the cleric that he bore the whiff of the Helpers of the Mahdi.

During this period Palestinian militants operated from southern Lebanon to exchange fire with Israel, which repeatedly mounted brutal incursions – not dissimilar to today’s campaign – in order to punish the locals, and soon set up a proxy southern Maronite militia that fought both Sunni Palestinians and Shia Lebanese. These Israeli attacks strained the relationship between the Palestinians and the southern Shias, to the extent that Amal offered little resistance when in 1982 Israel mounted a massive invasion of Lebanon. This Israeli assault was followed by a less brutal but equally galling occupation by its American suzerain, which set up its regional command for the Middle Eastern and North African region, Central Command or Centcom.

With Sadr long since vanished, Nasrullah and many other Shia militants saw little use left for Amal and instead set up separate cells to fight the Israelis, influenced in particular by the Iranian revolutionary regime. Among other tactics, they pioneered the first suicide attacks in the modern Middle East. Led by Ridwan Mughnie, a secretive but ruthlessly effective militant commander with close links to Iranian intelligence, such militants led a massive bombardment on the American barracks at Beirut in October 1983, which killed hundreds and forced the Americans to leave. The Israelis, however, never left, and by the mid-1980s the Iran-influenced Shia militants had united in an organization that called itself Hezbollah.

Hezbollah, backed by Iran, differed from Amal, which was backed by Syria, in that it openly worked with Sunni militants, Palestinians, and otherwise. During the late 1980s, indeed, the two Shia groups repeatedly clashed until Tehran and Damascus reached an understanding. Though Amal benefited from Syria’s longstanding occupation of northern-central Lebanon by monopolizing the formal parliamentary speakership reserved for Shias, it was Hezbollah whose influence would soar over the succeeding years by virtue of its hit-and-run raids against the Israeli occupation in the south.

Axis of Resistance

Nasrullah took over the leadership in 1992, by which point Israel had already captured or killed several of his predecessors. With Syrian help, in 1998 he thrust aside a bid for leadership by the group’s founder, Subhi Tufaili, who took a newly anti-Iran stance that annoyed both Damascus and Tehran. The rest of his time was spent organizing the war in the south, assisted by a capable field commander Nabil Qaouk, and building coalitions across the Lebanese political arena. In a field that had rested on sharing government posts by confession, Hezbollah championed the language of resistance to Israel – rather than backroom deals between various confessional blocs – as its major selling point.

In May 2000 Hezbollah’s strategy was vindicated when Israel finally withdrew from southern Lebanon, taking with them the collaborating militia led by Maronite commander Antoine Lahed. Yet Hezbollah did not attempt to take over Lebanon by force, instead building a “shadow state” that overlapped with much of the country’s weak political structure. Nasrullah’s charisma, political sophistication, and organizational skill made him Lebanon’s best-recognized militia leader, and he built diverse links far beyond the Lebanese Shia whose confidence his group had championed. His admirers included the Palestinian leftist Edward Said, the former Maronite army commander Michel Aoun, and even the onetime Sunni prime minister Rafic Hariri – a figure close to both Saudi Arabia and the United States, but one who applauded Nasrullah’s vigor. Even American leader George Bush II at one point flirted with the idea of Hezbollah entering formal politics in return for abandoning militancy – a flirtation that the group ignored.

Hezbollah’s particular mastery of the Lebanese arena was enhanced by, and in turn made the group more valuable to, a network of Iran-backed militias in the region that would eventually take on the moniker “Axis of Resistance”: resistance to the American-propped regional order with Israel at its apex. To some extent this was hype – Iran had, after all, assisted both the American invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq – but with Tel Aviv prodding Washington against Tehran, it was clear by 2005 that a confrontation was brewing. That spring Hariri’s assassination – widely blamed on Hezbollah, though without proof – triggered major unrest that forced Syria to quit its longstanding occupation of Lebanon as an American-friendly government led by Fouad Siniora won power.

However, this government was humiliated the following summer during yet another Israeli attack on Lebanon, which made a virtue of savagery – the term “Dahia doctrine”, named after a Beirut suburb, was coined by Israeli military commander Gadi Eizenkot to describe collective punishment as a strategy – but which was fought to a standstill by Hezbollah. Once more, Nasrullah’s prestige soared: he was seen as a champion of Lebanese independence, of resistance to Zionism, and even – in an age where sectarianism was spiraling, particularly in Iraq – a champion of cross-sectarian solidarity. Hezbollah’s much-vaunted links with Palestinian groups such as Palestinian Jihad and Hamas lent credence to these claims.

Yet at its root Hezbollah was a fundamentally pragmatic vassal of Iran, its immediate priority the maintenance of its own, and Iranian, influence in Lebanon. The group refused to take the bait when Israel and the United States provocatively assassinated Ridwan Mughnie in 2008, instead opting to force out Siniora’s government after a showdown over control of the capital’s airport. Similarly, subsequent Israeli assaults on Hamas-ruled Gaza provoked no Hezbollah escalation, though the Lebanese and Palestinian militants surely shared military resources and know-how.

Syrian Interlude and the Limits of Cross-Sectarian Solidarity

It was instead in 2010s Syria that Hezbollah mounted its next major military expedition. A major war broke out when the largely minoritarian Syrian regime of the Assad family bloodily cracked down on opposition, which quickly gained material support from Turkiye, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia. With historically Saudi-friendly Lebanese politicians such as Hariri’s son Saadeddine lending support to the budding Syrian insurgency and the United States making largely empty promises of support, Hezbollah and Iran reacted by bolstering crucial support to the government.

As Nasrullah railed against a “takfiri” conspiracy to oust the Syrian government, Hezbollah’s thunderous intervention at Qusair from May 2013 marked a turning point in the war. The militia deployed at major faultlines in Homs and Qalamoun, rescuing a teetering regime in spite of their distaste for some of its more sadistic measures. Iran and its allies portrayed the Syrian insurgency as a conglomeration of extremists and American stooges in service of Zionism: the road to Jerusalem, Nasrullah proclaimed in borrowing a common Iranian talking point, went not through the straight southern route but north through Syria.

In fact, as the mid-2010s showed, neither “takfiris” nor Zionists nor even the United States were prepared to topple the Syrian regime. Daesh’s emergence on the Iraqi-Syrian borderland was fought by the Syrian insurgents before it was fought by Iran; Israel was leery about what might replace the predictable Assads; and the United States soon made support to Syrian militants contingent on their fighting Daesh and not the regime. Indeed such Palestinian militants as Hamas were ranged in Syria on the side of the supposedly “Zionist” insurgents, not the regime: a stance that strained but did not snap their relations with Tehran.

By contrast, Hezbollah was wholeheartedly and decisively arrayed with Iran on Assad’s side, and though they did not indulge in the worst of the regime’s atrocities, the frequent sectarianism and abuses by the Iran-backed coalition made a mockery of their claims to cross-sectarian resistance. The Hezbollah of the 2010s – willing to engage in and rationalize assaults against Syrian Sunnis on behalf of a tyrant in Damascus – was a creature far different from the Hezbollah of the 1980s, which had fought alongside Lebanese Sunnis against the Assads’ vassals.

Unwanted Escalation

By the early 2020s, the war in Syria was beginning to abate – though Hezbollah continued to deploy at insurgent enclaves in the north – and heated up in Palestine once more. By this point the United States and Gulf states had lost interest in Syria entirely, and were bolstering the absurdly misnamed “Abraham Accords”, a very unAbrahamic coalition of Israeli ethnonationalists and Arab despots that sought to normalize their relations in a joint coalition against Iran by selling the Palestinians downriver. Naturally, this provoked Palestinian outrage, which repaired the links with Hezbollah. Repeated, bloody Israeli massacres and the ongoing blockade of Gaza provoked a mass counterattack, led by Hamas, in October 2023 – to which Israel responded with a nakedly genocidal onslaught.

Hezbollah and Iran had been taken aback by the Palestinian raid and by the brutality of the Israeli assault. Tehran avoided taking the bait of repeated Israeli escalations, realizing that Benjamin Netanyahu-Mileikowski wanted to drag it into an existential war with the United States. Hezbollah, as Iran’s vassal, acted somewhat more freely by exchanging cross-border fire into northern Palestine, which sent much of its settler population scurrying for cover but which also killed scores of Hezbollah fighters and many commanders. Though it dwarfed the reaction of pro-American Arab regimes, this was still a fairly muted reaction and fell short of Israel’s wish for a regional conflagration. So in September 2024, Tel Aviv flung down the gauntlet with brazen, brutal escalation in Lebanon.

Days after the murderous detonation of rigged pagers throughout Lebanon, Israel mounted a massive bombardment of Lebanon that killed hundreds within a day. In a repeat of 1982, they went even further by bombarding Hezbollah’s secret headquarters in Beirut. Along with an Iranian officer, Abbas Nilforoushan, the attack killed a dizzying array of Hezbollah leaders, including its ground commander Tahsin Akil and air commander Husain Surour: eventually, it was confirmed that the casualties included Nasrullah himself. Though it is certain that this will not end their troubles in Lebanon – for every Israeli aggression has provoked local backlash over the past fifty years – it is nonetheless indisputable that among the tens of thousands of innocents, they have killed in the past year, the Israelis have chanced upon a very big fish.

Related:

– Lebanon Faces Deadliest Day In Two Decades As Israeli Strikes Kill Over Five Hundred

– Iran President Ebrahim Raisi’s Controversial Career Ends In A Helicopter Crash

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Ibrahim Moiz is a student of international relations and history. He received his undergraduate degree at the University of Toronto where he also conducted research on conflict in Afghanistan and Pakistan. He has written for both academia and media on politics and political actors in the Muslim world.

The Muslim Bookstagram Awards 2024 Winners

Getting to Know A Potential Husband/Wife? 3 Questions To Ask Yourself First.

Study Classical Texts the Traditional Way | Session 15

Study Classical Texts the Traditional Way | Session 14

The Fiqh Of Vaginal Discharge: Pure or Impure?

The Coddling Of The Western Muslim Mind: [Part 1] The Cult Of Self-Esteem

Family Troubles Of The Prophets: A MuslimMatters Series – [Part II] My Kids Are Out Of Control

The Coddling Of The Western Muslim Mind: [Part II] The Islam Of Emotionalism

Study Classical Texts the Traditional Way | Session 9

I’ve Converted, And It’s Christmas…

Study Classical Texts The Traditional Way [Session 1] | Sh. Yaser Birjas

Sami Hamdi: “Muslims Must Abandon Harris” | Transcript and Summary

IOK Ramadan: The Importance of Spiritual Purification | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep30]

IOK Ramadan: The Power of Prayer | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep29]

IOK Ramadan: The Weight of the Qur’an | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep28]

Trending

-

#Islam1 month ago

[Podcast] Navigating Christmas: Advice to Converts, from Converts | Hazel Gomez & Eman Manigat

-

#Life4 weeks ago

The Coddling Of The Western Muslim Mind: [Part 1] The Cult Of Self-Esteem

-

#Islam4 weeks ago

Family Troubles Of The Prophets: A MuslimMatters Series – [Part II] My Kids Are Out Of Control

-

#Current Affairs1 month ago

Addressing Abuse Amongst Muslims: A Community Call-In & Leadership Directives | The Female Scholars Network