#Islam

Hijab And Jilbab In the Quran: On The Hermeneutics Of The Quranic Verse Of Khimar

This article is a contribution to hermeneutics (uṣūl al-taʾwīl) with a specific focus on khimār, which is commonly known as the hijab.

Published

This article was first published here.

Table of Contents

Abstract

This article affirms revelation as a source of knowledge in Islamic epistemology. It proceeds to map out the hermeneutical framework for reading the Qurʾān and Sunnah. This framework is applied to the verse of khimār. The article then explores the meaning of khimār and its usage in the pre-Islamic, prophetic, and post-prophetic eras. Having established its meaning and usage, it identifies the locus of its legal value.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

In light of its legal value (jihat al-ḥukm), the paper explores the reports documenting the occasioning event (sabab al-nuzūl) of this verse and the ratio legis (ʿilla), the purpose of each interpretive tool, and their (mis)appropriation.

Once its legal value has been established, the paper focuses on common contentions on the obligation of khimar, and identifies the methodologies that give rise to these contentions.

The final section of the article explores how the hijab can be related to other values of Islam, and how to proceed forward with a comprehensive outlook on the hijab from both a physical and metaphysical perspective.

The following verses will be the focus of this paper:

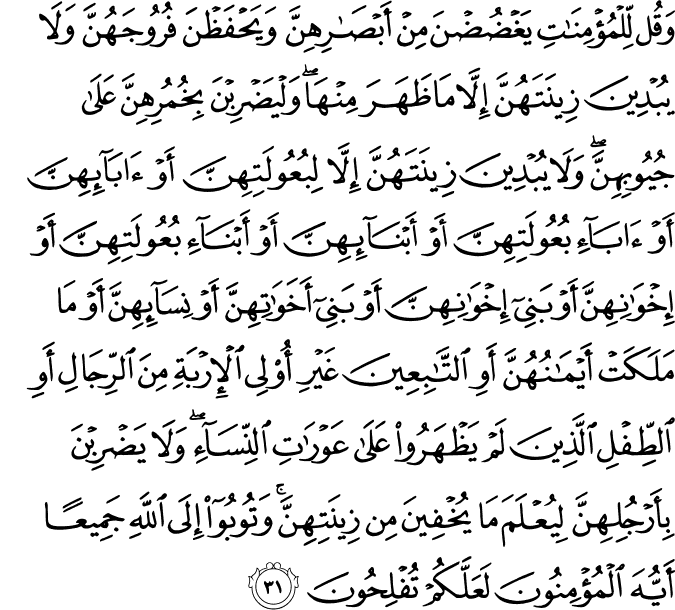

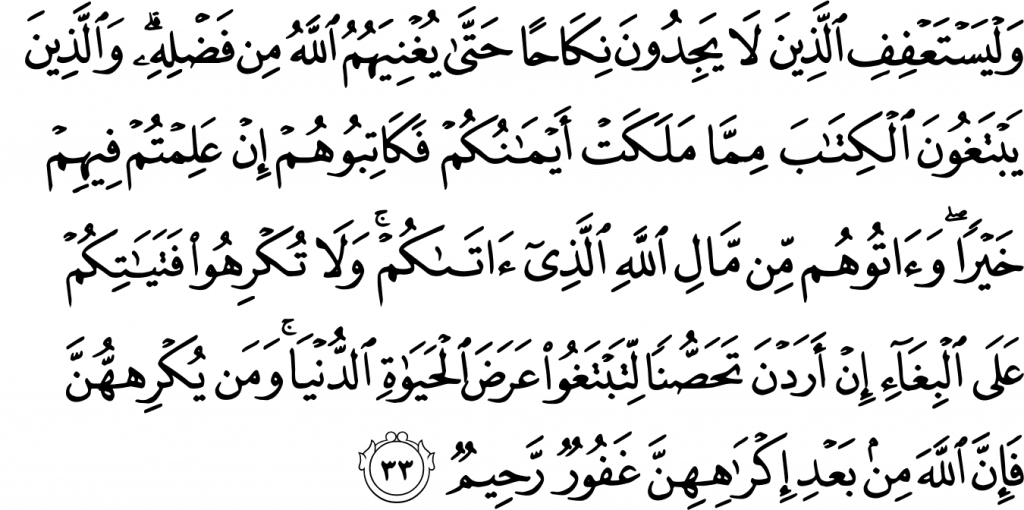

The verse of khimār:

And tell believing women that they should lower their glances, guard their private parts, and not display their charms beyond what [it is acceptable] to reveal; they should let their khumur1Key terms are deliberately left transliterated fall to cover their necklines and not reveal their charms except to their husbands, their fathers, their husbands’ fathers, their sons, their husbands’ sons, their brothers, their brothers’ sons, their sisters’ sons, their womenfolk, their slaves, such men as attend them who have no sexual desire, or children who are not yet aware of women’s nakedness; they should not stamp their feet so as to draw attention to any hidden charms. Believers, all of you, turn to God so that you may prosper2Quran, al-Nūr:31, translation Abdel Haleem..

Occasioning event (sabab al-nuzūl): Women used to leave their necks exposed when they wore the khimār. God revealed the verse to qualify the way they wore their khimār by ordering them to let their scarves fall to cover their necklines.

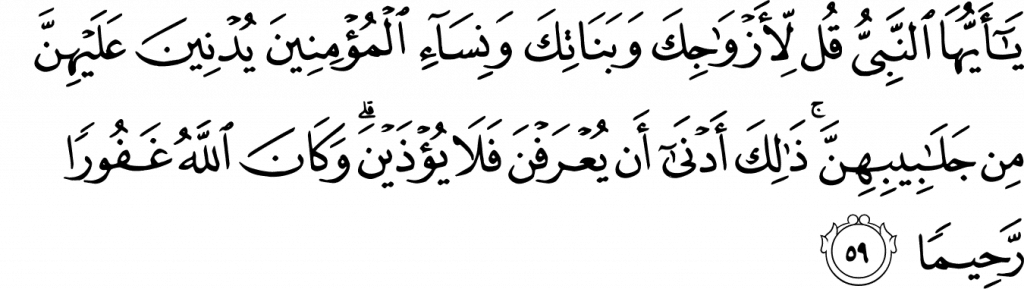

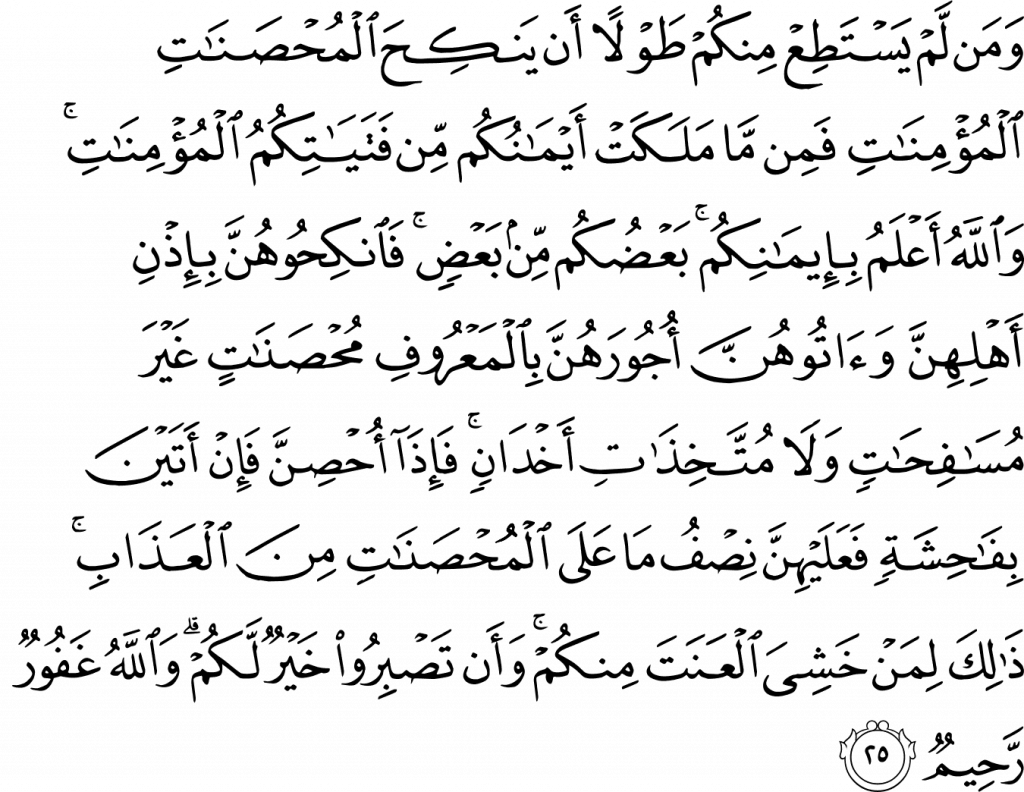

The verse of jilbāb:

Prophet, tell your wives, your daughters, and women believers to make their jalābībihinna hang low over them so as to be recognised and not insulted: God is most forgiving, most merciful.

If the hypocrites and those in whose hearts is disease and those who spread rumours in al-Madinah do not cease, We will surely incite you against them; then they will not remain your neighbours therein except for a little3Quran, Aḥzāb:59–60, translation Abdel Haleem..

Occasioning event (sabab al-nuzūl): Immoral men used to harass women when they came out in the evening to relieve themselves. Women were told to lower their jilbāb when they went out in the evening so they could be recognised and not harassed.

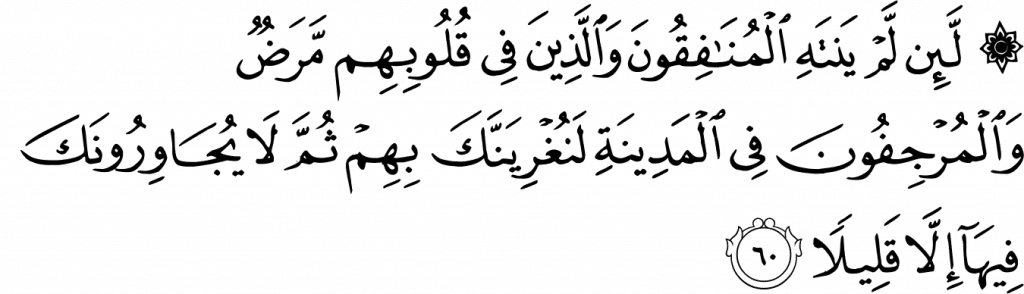

Epistemology

Revelation is a source of knowledge and perennial truth for Muslims after belief in God. The purpose of revelation is to establish a relationship between human beings and the Divine in order for them to know what God requires of them. That revelation confirms itself as a source of knowledge is clear in many verses, one such verse being,

This is the Book (His Divine Writ) wherein there is no doubt (in it, is) a guidance for God conscious people, who believe in (the existence of) the unseen (metaphysical reality) and are constant in prayer and spend on others out of what We provided for them as sustenance4Qurʾān, Baqara: 2–3.

From the above verse, we can gather that in Islamic epistemology, revelation functions as an independent source of knowledge. It provides a description of reality, which encompasses both the realities of the observable and the unseen world.

In Islam, God is both creator and divine legislator (Shāri’). Revelation imparts functional knowledge (Divine law) of peoples’ obligation to God (e.g. prayer) known as ḥaqq Allah, and their obligation to each other (e.g. spending on others) known as ḥaqq al-ʿibād. Knowledge of the Divine law allows people to know their rights, responsibilities, and duties (ethics) in this world. Altogether, revelation can be described as a source of knowledge, which provides a true description of reality, and it provides a system of beliefs and practices.

The hermeneutics of language

The medium by which the Divine law is passed on to the human realm is through the Messenger of God

As His Divine law is communicated through the vernacular of its first recipients, legal theorists in the post-prophetic era were left to imagine and re-construct the law according to how the first recipients of revelation had witnessed and experienced it. This required the formulation of a hermeneutic of language. But they were not without a hermeneutical context. The context emerged through an interplay of the human effort to understand the intent of God’s word, which was achieved through the Messenger’s

El-Shamsy similarly explains (in another context) that a ‘sola scriptura perspective’ of jurists approaching the text with no hermeneutic context is inconsistent with historical reality. Historically, an autonomous Muslim community (the Ṣaḥāba) existed well before the completion of the written Qurʾānic corpus. Communal practice carried its own Islamic normative weight, through which subsequent readings of the Qurʾān were to be applied5Ahmed El-Shamsy, review The formation of Islamic hermeneutics, David R. Vishanoff. Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 39. 2014, pp. 168–171.. In the process of discovering the meanings of the Divine law, jurists considered the lexicon formed during the period of revelation. The Qurʾān also points to this hermeneutic approach in the following verse:

So, [O Muhammad], We have only made Qurʾān easy in the Arabic language that you may give good tidings thereby to the righteous and warn thereby a hostile people6Qurʾān, Maryam:97..

The verse highlights intelligibility and accessibility of knowledge as the primary purpose of the Qurʾān being revealed in the vernacular of its recipients. Ibn Fāris7For more biographical information on Ibn Faris, see The Biographical Encyclopedia of Islamic Philosophy, ed. Oliver Leamen, (KentuckyL Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015) p. 180 (d. 395), a prominent lexicographer, explains in his book, ‘Al-Ṣāḥibī fī fiqh al-lughah wa sunan al-ʿarab fī kalāmihā (Al-Ṣāḥibī in the law of the language and the usages of the Arabs in their speech):

Knowledge of the Arabic (vernacular) is imperative to understand the Qurʾān and Sunna as revelation came down in the lexicon formed during that period8Aḥmad ibn Fāris, Al-Ṣāḥibī fī fiqh al-lughah wa sunan al-arab fī kalāmihā, edited by Aḥmad Saqar, 1st ed., (‘Esa al-bābī al-ḥalabī wa shurakāh, nd.) p.50.

Elsewhere, he elaborates on this point by pointing to the poetry of the Arabs being used as a source of evidence (iḥtijāj). This is most likely inspired from the incident of Sayyid ʿUmar who encouraged people to learn pre-Islamic poetry to understand the Qurʾān when he himself discovered the usage of a Qurʾānic word through poetry. He said to them, ‘there lies the key to the explanation of your Book and the sense of your speech.9Narrated Saʿīd b. al-Musayyab. See Muhammad Shafi, Maʿāriful Qurʾān (Maktaba-e-darul-ʿulūm, nd.) p. 366’ In other words, it is imperative to consider the prophetic milieu and the realities that the recipients of revelation were experiencing as revelation came down to instruct, advise and refine them.

Although, there are non-linguistic dimensions of legal theory, such as the role of ḥadīths, abrogation, or reasoning by analogy etc., a ‘ruling’ so to say is still considered to include the process of deriving a specific linguistic meaning or signification of a verse, which impacts the intended meaning (murād) of a ruling, its legal value, and how to implement it. Hence-why legal theorists usually began with categorizing words in terms of their usage.

A word (lafẓ) has a normative meaning (ḥaqīqī). Normative meanings are classified into: lughawiyya, ʿurfiyya, and sharʿiyya.

– Ḥaqīqa lughawiyya: The literal/lexical usage of a word.

– Ḥaqīqa ʿurfiyya: The conventional usage of a word. For example, the ḥaqīqa ʿurfiyya of walad (lit. child) means son, not daughter.

– Ḥaqīqa isṭilāḥiyya10Some scholars maintain that the Sharīʿa does not introduce a new meaning to a word, which is already known by the people. Rather, it determines a word’s qualities, forms, and conditions and obligates its addressees to perform them. See Ibn Fūrak, al-Ḥudūd fī al-uṣūl, (quoted from Sharh al-‘ālim wa-l-mutaʻallim), edited by Muhammad al-Sulaymani, 1st ed., (Dār al-gharb al-islāmī, 1999), pp. 108–09. See also Mehmet Bulğen “The power of language in the classical period of kalam” in Nazariyat, Journal for the history of Islamic philosophy and sciences, vol, 5, 2019, pp. 67–8.: The usage of a word according to a specific convention. This includes shar’ī definitions (a specific definition given by the lawmaker). For example, Salah (lit. duʿā ‘prayer’) is a prayer with specific movements and utterances, performed in a state of ritual purity and at calculated times.

An expression is understood to be prima facie conveyed through the normative meanings of the component words unless there is a contextual indicant (qarīna) to suggest otherwise. The prima facie (ẓāhir) meaning includes all three normative usages, and the context in which the expression is conveyed provides the intended meaning (murād/naṣṣ) of the ‘speaker.’ For example, an imperative expression as understood from the normative meanings of its component words requires performance, unless there is extraneous evidence of the same level of certitude or higher than it as to change its meaning. For this reason, legal theorists make a very fine distinction between the prima facie (ẓāhir) meaning and the intended meaning (murād/naṣṣ) of an expression.

The relation between the expression and its intended meaning is expressed in terms of clarity (wuḍūḥ). The degree of clarity of the intended meaning (murād or naṣṣ) is greater than the degree of clarity of the prima facie (ẓāhir) meaning of the same expression11Two more classifications are subsumed under naṣṣ: Mufassar ‘explained’: The legislator (shāri’) adds further qualification to a meaning (naṣṣ). For example, the meaning of the Salah has been elucidated by the blessed Prophet. It has no possibility of re-interpretation other than abrogation. Muhkam ‘firmly constructed’: This includes doctrine (i’tiqad) and akhbār (stories about past nations). It has no possibility of re-interpretation or abrogation.. The prima facie meaning has the least degree of clarity and consequently, the more probable chance of being re-interpreted. In theory, ẓāhir was classed as a secondary implication. On the spectrum of epistemological certainty then, the level of certitude (yaqīn) increases with the level of clarity.

To give an example of the relationship between the two terms, we will explore their usage in the following verse:

But those who take usury will rise up on the Day of Resurrection like someone tormented by Satan’s touch. That is because they say, ‘Trade and usury are the same, but God has allowed trade and forbidden usury12Qurʾān, Baqarah:275. Translation Abdel Haleem. Italics mine..

The prima facie (ẓāhir) meaning of the verse is that God has allowed trade (bayʾ) and forbidden usury (ribā). However, the reason or intent behind the revelation of the verse was to negate the similarity between bayʾ and ribā. This is taken to be the intended meaning (naṣṣ).

Pre-Islamic, prophetic, and post-prophetic usage of khimār

The aforementioned linguistic categorizations will be used to construct a hermeneutical framework from which the verse of khimār in Sūra Nūr will be analysed to show:

- The meaning and usage of the term khimār.

- The reception of the verse in the prophetic and post-prophetic eras.

- The legal value of the verse.

And tell the believing women that they should lower their glances, guard their private parts, and not display their charms beyond what [it is acceptable] to reveal; they should let their khumur fall to cover their necklines (juyūb)13Qurʾān, al-Nūr: 31. Translation Abdel Haleem..

Khimār is the singular term for khumur, akhmira and khumr. Khimār literally (ḥaqīqa lughawiyya) means ‘a covering’14Ibn Mandhūr, Lisān al-‘arab.. According to its conventional usage (ḥaqīqa ʿurfiyya), the word khimār means a head-covering. This was the common usage (and practice) before the inception of Islam, and it continued in Islam as a normative feature of the Muslim community. The affirmation or amendment of various conventional practices to become specific conventional practices (ḥaqīqa sharʿiyya) by God, the Lawmaker, was not uncommon. For example, the zawāj al-ṣadāq, which was a pre-Islamic practice of nikāḥ became the Islamic normative practice of nikāḥ. However, in the pre-Islamic custom, the dowry was paid to the family rather than to the woman. This practice was modified in Islam to allow full entitlement of the dowry to the woman who is perceived as an autonomous agent in Islam15Majid Khadduri, “Marriage in Islamic Law: The Modernist Viewpoints.” in The American Journal of Comparative Law, 26/2 (Spring,1978), p. 213.. Similarly, we begin with accounts of the conventional usage of khimār to meaning head-covering (and in practice) through pre-Islamic poetic dicta16For further reading on types clothing of the pre-Islamic era traced in poetry, see Yahya Jabbouri, “al-Malābis al-ʿarabiyya fī al-shiʿr al-jāhilī” in the Annual Journal of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Qatar, vol. 9, 1986, p. 259.

In the Mufaḍḍaliyāt –an anthology of pre-Islamic Arabian odes- Al-Mufaḍḍal al-Ḍabbī (d.780) records a poem from ‘Awf bin ‘Aṭiyya who describes a group of women becoming alarmed by an incursion, such that some of the women’s head coverings fell to the ground:

When the women were bare headed like bamboos

Amongst women who had their head-covering (khimār) on, and her sister

Ran while her waistband was in the place of her lower garment17(It was tightened so she could run faster) Al-Mufaḍḍal al-Ḍabbī, Mufaḍḍaliyāt, edited by Aḥmad Shakir and ʿAbd al-Salam Harun, 6th ed,. (Cairo: Dār al-ma’ārif, nd.) p. 327.

Ibn Qutayba records an incident about al-Khansā’, born ca.575, who sought assistance from her brother, Ṣakhr. He replied with the following lines:

By God, I will not give her the worse half;

She is a chaste woman who has caused me no shame;

And were I to die, she will tear up her head-cover (khimār)

And wear a mourning blouse (made of) hair18Al-Jahiẓ, attrib., al-Maḥasin wal-aḍḍāḍ (Cairo: Maktabat al-Qahira, 1978), p. 104..

Ṭarafa bin ʿAbd (d.569), one of the poets of the Muʿallaqāt, describes his state from recklessness to sensibility like a person whose head was covered and suddenly the covering was removed:

I was amongst you like the one whose head was covered

Then one day, both my disguise and the head-covering (khimār) were exposed19Ṭarafa bin ʿAbd, Dīwān Ṭarafa, (Beirut: Al-Muʾassasa al-ʿArabiyya lil-dirāsāt wal-nashr, 2000) p. 80..

In the verse of Sūrah al-Nūr, women are commanded to use their khimār to cover their necklines (juyūb), because the way in which the khimār was conventionally worn at the time was that the women would cover their hair and keep their neck exposed20Abu Ḥayyān al-Andalusi, Tafsīr bahr al-muhīt (Beirut: Dār al-Fikr, 2010) vol. 8, p. 34.. Al-Ṭabarī explains that women were commanded to wrap their khimār over their jayb to cover their hair, neck and ears21al-Ṭabari, Jāmiʾ al-bayān ʿan taʾwīl āyil Qurʾān, vol.19, p. 169.. This is the occasioning event (sabab al-nuzūl) of the verse. God did not specifically command women to cover their hair as the ẓāhir meaning of khimār is a head-covering, whereas the naṣṣ in this case is to draw the khimār over their necklines. It would be similar to telling someone, ‘pull the tablecloth over the chairs’ without needing to say ‘cover the table.’ God, as Lawmaker, thereby qualifies the conventional usage (ḥaqīqa ʿurfiyya) of khimār to a specific conventional usage (ḥaqīqa sharʿiyya).

The ḥaqīqa sharʿiyya usage of khimār

The now normative meaning of khimār to include the neckline can be identified in traditions reported during the prophetic and post-prophetic eras. Imām Bukhārī records in his Ṣaḥīḥ that Sayyida Aisha reported:

The Prophet was offering the dawn prayer, and some believing women covered with their veiling sheets (mutalafiʿāt fī murūṭihinn) used to attend the Fajr prayer with him. They would then return to their homes unrecognized22Muhammad Ismail al-Bukhārī, Ṣaḥīḥ Bukhārī no. 584., vol. 1 p. 565. Muslim bin al-Hajjāj, Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim no. 639, pp. 373–374, Abū Dawūd, Sunan Abī Dāwūd, no. 422, p. 335, Abū ‘Īsā al-Tirmidhī, Sunan al-Tirmidhī no. 155, p. 374, Abū ʿAbd al-Rahmān al-Nasā’i, Sunan al-Nasā’ī no. 1287, Abū ʿAbd Allāh Ibn Māja, Sunan Ibn Māja no. 633, p. 400., (Dār al-Ta’ṣīl, 2012).

Additionally, a variant of this ḥadīth is also recorded in the Muwaṭṭa. In his commentary of the Muwaṭṭa, Ibn Ḥabīb (d. 238/852) explains that talaffuʾ is to take the veil over the head23 See Sharḥ al-Zurqānī ‘alā al-Muwaṭṭaʾ (DKI, 2011) vol 1, p. 30.

Imam Muslim records a tradition that Sayyida Aisha raised her khimār and exposed her neck while travelling: ‘fa-jaʿaltu arfaʿu khimārī aḥsuruhu ʿan ʿunuqī.’ (in the same tradition, she asks her brother who accompanied her whether there was anyone else around)24Muslim bin al-Ḥajjaj, Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim (Riyadh: Dār Tayyiba, 1426AH) p. 547..

The normative meaning of khimār was not restricted to the prophetic community. ʿAbd al-Razzāq reports from ʿIkrima (d.105/723) that he said,

If a woman were to use a piece of clothing (thawb) to cover her hair until nothing shows, it will suffice her in place of a khimār25Muṣannaf, 5086.

When Imām Mālik (d.179/795) was asked whether a man could wipe over his turban (ʿamāma), and whether a woman could wipe over her headscarf (khimār), he replied that they must wipe over their heads26Ibid..

Muḥammad al-Shaybānī (d. 805) records in his narration (riwāya) of the Muwaṭṭaʾ that Nāfiʿ saw Ṣafiyya bint abī ʿUbayd (d.230/845) performing wuḍūʾ. She removed her khimār and wiped over her head27Muḥammad al-Shaybānī, Muwaṭṭa al-Imām Mālik, edited by ʿAbd al-Wahhāb ʿAbd al-Latīf, 4th ed., (Cairo, 1993) p. 45. In the riwāya of Yahya al-Laythī, Nāfi’ adds, ‘and I was a prepubescent boy then.28Yaḥyā al-Laythī, Muwaṭṭa al-Imām Mālik, edited by Bashār Awwād Maʿrūf, 2nd ed., (Beirut: Dār al-gharb al-Islāmī, 1997) pp. 74–75’

Reports from the post-prophetic era adduce that the verse of khimār was understood to mean a head covering by successive communities of the post-prophetic era.

The distinction between sabab al-nuzūl and ʿilla

Considering the conventional usage of khimār, further instructions on the correct manner of wearing the khimār are found in the reports documenting the occasion that this verse was revealed in (sabab al-nuzūl). This brings us to the distinction between a sabab al-nuzūl and the ratio legis (ʿilla). Both are considered interpretive tools but with different functions. Where the ratio legis (ʿilla) is the cause of the legal obligation, the purpose of a sabab al-nuzūlwas to provide a narrative account for the revelation of the verse in order to preserve the remembrance of revelation as a lived experience for its recipients, and as a sign of God’s concern for His creation.

Consider an example on the purpose of the ʿilla. The ʿilla for stopping at the traffic lights is the red light. Although, there are many reasons we can give for the benefits of stopping at the traffic lights, such as civilian safety or assigning right-of way, this does not alter the fact that the ʿilla for stopping at the traffic lights is the red signal. A Qurʾānic example can be adduced from the following verse:

And whoever among you is sick or has an ailment of the head [making shaving necessary must offer] a ransom of fasting [three days] or charity or sacrifice.29Qurʾān, Baqarah: 196’

This part of the verse was revealed about Kaʿb ibn Ujra who went to the blessed Prophet

… This was specifically revealed about me but it applies to all of you”30al-Wāḥidī, Asbāb al-Nuzūl, translation by Mokrane Guezzou (Amman: Royal Āl al-Bayt Institute for Islamic thought, 2008) pp. 15–16. Occasions of revelation like this do not restrict the applicability of the verses they have occasioned. The ʿilla (ratio legis) in the verse which initiates the ruling (ḥukm) of fasting, charity or sacrifice is the act of shaving the head (out of necessity).

As for the ʿilla of khimār, it is explicitly identified (ʿilla manṣūṣa) by God, the Lawmaker, in His address,

say to the believing women.31al-Ṭabari, Jāmi’ al-bayān ‘an taʾwīl āyil Qur’ān, edited by ʿAbdullah al-turkī., (Cairo: Dār al-Hajr, nd.) vol.19 p. 169.’

The cause for the legal obligation of covering the hair as part of ʿawra is for a Muslim female to have acquired legal capacity (ahliyya)32For detailed discussion on legal capacity, see al-Sarakhsī, Uṣūl al-Sarakhsī, (Cairo, 1372) vol 2, p. 233.. From the conditions of capacity to carry out the command is ʿaql (full development of the mental faculty). One of the criteria to assess ʿaql is bulūgh (puberty) by which a female is considered a woman.

The ʿilla for the obligation of khimār can also be identified in the prophetic traditions, which are used to explain the intended meaning of the verses.

The four Imāms of the Sunan, Abū Dāwūd, al-Tirmidhī, al-Nasāʾī, and Ibn Mājah, and others have reported that the blessed Prophet said,

Allah [only] accepts the prayer of a ḥāʾiḍ in a khimār.’ The ḥāʾiḍ is the one who has experienced menstruation, which is considered a sign of maturity (bulūgh)33This ḥadīth has also been narrated by Aḥmad and Ḥākim. Ibn Khuzayma determines it as saḥīḥ

Similarly, the Imāms of the Sunan report from ʿUqba bin ʾĀmir who said, ‘News reached the blessed Prophet that a woman vowed to perform the pilgrimage bare-headed (ḥāsiratan). The blessed Prophet

The foregoing distinction between the ʿilla and the sabab al-nuzūl is important in order to understand the forthcoming discussion on ʿilla and the legal status of the verse of khimār. Once the distinction between sabab al-nuzūl and ʿilla has been established, legal theorists will identify the locus of its legal value.

The locus of the legal value of khimār as part of ʿawra

The verse of khimār is in the imperative form, and its form is legally understood to convey the meaning of obligation unless there is enough contextual evidence that constitutes the same degree of certainty as to change its legal value. As explained previously, the purpose of revelation is to provide functional knowledge so that we can achieve obedience of God, and it is also the reason why God chose to express Himself through the imperative (‘do’) and prohibitive terms (‘don’t) for the most part of revelation. There are various grammatical imperative forms that can be identified in the Qurʾān. The imperative in the verse of khimār is in the form of a (informative) sentence (jumla khabriyya). Another example of a jumla khabriyya conveying a command is the following verse,

So whoever sights (the new moon of) the month (Ramadan), he shall fast it.34Qurʾān, al-Baqara:185’

Conveying an obligation in the form of a jumla khabriyya usually gives the added meaning of stressing the urgency of the command.

The purpose of establishing the obligation of the khimār is to define the parameters of the ʿawra for a Muslim woman. The ʿawra is the nakedness of a person, therefore, uncovering the ʿawra is uncovering one’s nakedness. The obligation of covering the ʿawra means to cover those parts of the body that are considered the nakedness of a person in the presence of others. Depending on whose presence a person is in, certain parts of the body may or may not be considered an ʿawra in front of them. For example, there is no ʿawra for a husband in front of his wife. For a woman in the presence of people not stated by God in the verse of khimār, her nakedness (ʿawra) includes her hair and neckline. The obligation of covering the ʿawra is a core value of Islam and the clothing, whether it is called the khimar, chādar or the hijab, are means to achieving the obligation.

The obligation of covering the ʿawra is a core value of Islam and the clothing, whether it is called the khimar, chādar or the hijab, are means to achieving the obligation.Click To TweetAltogether, the prima facie (ẓāhir) meaning of the verse as understood from the normative usage (ḥaqīqa) of the component words is that God commands the believing women to draw the khimār over their necklines. It was already the normative practice for women to cover their hair but they left their necks exposed, hence the intent of the verse (naṣṣ) was to command women to cover their necklines. The verse is revealed in the imperative form (ʾamr), which constitutes an obligation qua obligation because there is no extraneous evidence of the same level of certitude contrary to it as to change its legal value. Therefore, it has no possibility of re-interpretation other than abrogation by the Lawmaker.

At this juncture, it is necessary to address the relationship of prophetic ḥadīths to the Qurʾān in interpretation, and the difference between ḥadīths and generic historical reports.

If a legal ruling has been established from the primary revelatory source, the Qurʾān, the examination of the chains of ḥadīths is for the purpose of affirming and supplementing our understanding of the legal ruling, not to dispute it. In this vein, ʿAllāma Kashmīrī explained that the (reason for) verifying reports through their isnād is to prevent anything that is not part of the dīn, not to exclude what is (already) established in the dīn35See Abu Ghudda “al-Mulḥaq al-mu’anwan bi-wujūb al-‘amal bil — ḥadīth al-dha’īf idhā talaqqāhu al-nās bi al-qabūl” in al-Ajwiba al-fāḍila lil-as’ila al-‘ashara al-kāmila lil-Imām al-Laknawī’, 5th ed., (Dār al-Salām, 2007), pp. 237–238. On the principle of corroboration, see the section of “ḥadīth ḥasan”, al-Tirmidhī in Al-’ilal al-ṣaghīr. (Beirut: Dār al-iḥyāʾ al-turāth al-ʿarabiyy, 1938)..

Importantly — and this point expands on the hermeneutics of language — ḥadīth reports are one form of documenting the normative practice (sunnah) of the blessed Prophet

A tangential discussion is necessary to address the difference between ḥadīths and generic historical reports. An event that is cited to substantiate the claim that head covering is not part of the Islamic legal tradition is the historical report of the supposed refusal to wear a headscarf by Sayyida Faṭima al-Kubrā, the great granddaughter of the blessed Prophet

Legal obligations are moral values

As a legal obligation, covering the ʿawra is considered a moral value. Unlike in modern Western moral and legal philosophy where a dichotomy exists between law and morality, what is ‘legal’ in the Qurʾān is the ‘moral’37 See Wael B. Hallaq, “Groundwork of the Moral Law- A New Look at the Qurʾān and the Genesis of the Sharīʿa.” in Islamic Law and Society 16 (2009) pp. 239–279 for further reading on the split between moral and legal philosophy,. There are many instances in the Qurʾān where moral obligations are applied to legal injunctions. To suffice with one example, in the case of protecting the rights of women, the Qurʾān encourages the emancipation of slaves as a moral value. As for its moral principle, God states,

And what will make you realize what ˹attempting˺ the challenging path is? It is to free a slave..’38Quran 90: 12–13. Translation by Dr. Mustafa Khattab.

There are many areas of its legal application. To suffice with one example, God establishes the legal contract of mukātaba, where it is agreed that a slave will pay the master a certain amount to redeem themselves,

Those of your slaves who want mukātaba, do mukātaba with them if you recognise some good in them, and give them from the wealth that Allah has given you. And do not force your female slaves into prostitution if they want to be chaste for the love of the material of this world. Whoever forces them, truly Allah is forgiving and merciful (to the females) after they are coerced39Quran 24:33.

As well as legislating a mukātaba contract, the last part of the verse also bears legal import in that the punishment for zinā (fornication) is not applied to women who are coerced.

From a theological perspective, obligations are moral values by virtue of being obligations, whether God commands and rewards them because they are moral values40The Mu’tazila believe that moral values have an ontological reality, and one can have knowledge of God imposing moral obligation and the obligations themselves prior to God’s disclosure of them, or whether God assigns what He commands as moral values because He promises to reward them41. And uṣūl al-fiqh (legal theory) is about acquiring knowledge of the moral judgements of legal pronouncements.

The obligation of khimar is a moral value by virtue of being an obligation qua obligation, which means it remains immutable (thābit). Immutable aspects of Islam (thawābit), such as obligations and prohibitions, are not susceptible to change unlike the mutable aspects (mutaghayyirāt) of Islam. To explain, where obligations qua obligations are immutable, the means to achieve them are mutable. For example, covering the ʿawra (which includes the hair for women) is an obligation, whereas the clothing used are a means to achieve the obligation. Whether it is called the khimār, the chādar or hijab will depend on a person’s socio-cultural context (ʿurf). In other words, the means to fulfilling universal obligations that are non-local are locally expressed through rich and diverse cultures.

One can also understand from the thawābit and mutaghayyirāt that in spite of the different socio-cultural, economic or even political implications of the hijab, covering the ʿawra remains an obligation. By the 1980s in Turkey, studies on tesettur (a distinct urban style of covering, which includes the hair and body) show multiple appropriations of the hijab. For middle class women, it was used to express a particular lifestyle dress to distinguish themselves from their elite Western-oriented counterparts. This particular style of dress was then associated to university campus protests on the headscarf ban42Banu Gökarıksel and Anna Secor, “Marketing Muslim Women” in Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, Vol. 6, №3, (Fall 2010), pp. 118–148. Economically, the commodification of the hijab as a fashionable item makes regular appearances in trendy boutiques and on fashion runways. The complexities of its adoption by women in an interrelated web of class, lifestyle and taste-related identities and politics must acknowledged. The multiple appropriations of hijab do not, however, alter its legal value.

Objections regarding free and slave women; social status and safety

In this section, two common objections on the hijab will be explored. The first of these objections is that covering the hair is contingent on social status and physical safety. The second objection is that covering the hair is contingent on fitna (temptation).

The first contention we will explore is the issue of social status and physical safety. Relevant verses under this discussion include the verse of khimār and the verse of jilbāb.

The verse of jilbāb is as follows:

O Prophet, tell your wives, your daughters, and women believers to make their jalābīb (outer garments) hang low over them so as to be recognised and not insulted: God is most forgiving, most merciful43 Qurʾān, Al-Aḥzāb:59..

This verse is used by those who object to the obligation of covering the hair to make the following argument: The hijab was a social status marker, which served the purpose of differentiating between free and slave women. The phrase an yuʿrafna has been interpreted as ‘to be recognized’ as free women, and an incident between Sayyid ʿUmar and a slave girl is adduced as evidence.

We will first compare and analyze the two verses to identify the relation. We will then explore contentions regarding differences between free and slave women, and what this difference may or may not represent. We will then look at the incident of Sayyid ʿUmar and the slave girl to try and appropriate the verses in light of the normative practice at the time.

It is important to note that the probable cause that khimār negators (henceforth known as negationists) have identified, which is that the hijab was to differentiate between free and slave women, is not from the verse of khimār. Negationists use the verse of jilbāb to identify a probable cause for the verse of khimar. This is problematic in itself because the two verses were revealed for separate reasons. However, to really unpack the social status argument, it is important to understand the verse of jilbāb.

a) The meaning of jilbāb

The jilbāb is a material that is much wider than a khimār and it is used to cover the whole body, including the hair44Ibn Mandhūr, Lisān al-‘Arab. It has been described as a cloak (milḥafa), which is worn over the clothes45Yahya Jabbouri, “al-Malābis” p. 274.. The jilbāb was not solely used for the purpose of covering the ʿawra as the khimār was, rather it was seen as an extra piece of material which was worn over the clothing. It was not contingent on the legal ruling of covering the ʿawra, although, not completely exclusive of it either. To explain, ʿAbd al-Razzāq transmits in his Muṣannaf that ʿAṭāʾ said,

A woman will pray in her dirʾ, khimār and izār, and it would be preferable (aḥabb ilayya) for her to wear a jilbāb. I said: What if her dirʿ, khimār and izār are thin (as to be transparent)? He replied: then she should wear a jilbāb over them.46ʿAbd al-Razzāq, Muṣannaf, 5089.’

Although the jilbāb could be used to cover the ʿawra including the hair, it was seen as a separate item to the khimār.

Reflecting on the verse of khimār, what is important to note here, is that the Qurʾān does not make a clear distinction between free women and slave women, which naturally gave way to differences on whether the ʿawra of a free and slave woman was legally different or not. It is an opinion of the Shāfiʿīs, the Ḥanbalīs as well as of Ibn Ḥazm that there was no difference between the ʿawra of a free and slave woman. Al-Nawawī states, ‘the most correct verdict according to the scholars is that the enslaved woman is like the free woman.47Al-Nawawī, Minhāj al-ṭālibīn wa ‘umda al-muftīn, p. 204.’

Ibn Ḥazm quite vehemently opposes any difference between the ʿawra of a free and slave woman. He states in the Muḥallā that this verse is addressing free and slave women because they both fall under the category of ‘believing women.’

As for differentiating between the free and slave woman, then the religion of God Almighty is one, creation and nature are one. All of that in respect to free and slave women is the same, unless there is an explicit text to distinguish between them in any way such that it can be applied48 Ibn Ḥazm, al-Muḥallā (Beirut: DKI, 2003) vol. 2, pp. 248–249. Translation credit: Abu Amina Elias.

In fact, ʿAbd al-Razzāq transmits a report from Ibn Jurayj that the scholars of Medina obligated the khimār on slave women once they became mature, but not the jilbāb49ʿAbd al-Razzāq, Muṣannaf, 5111..

Nevertheless, the majority of jurists, including the predominant position of the Shāfi’ī school, did not consider free and slave women of the same legal category. Both were recognized as moral agents with legal obligations. In fact, it was not uniquely the case of ʿawra in which free and slave women legally differed, but they differed in over 50 legal rulings. For example, the legal punishment for committing a sexual crime for a slave is half the punishment of a free woman. The Qurʾān states,

…And when they are taken in marriage, then if they are guilty of a sexual offence, they shall have half the punishment which is (inflicted) upon free women.50 Qurʾān, al-Nisā’: 25’

Acknowledging this difference in the Qurʾān, jurists discussed legal differences between both free and slave women. Ibn Qudāma writes,

The prayer of a slave woman with her head unveiled is permissible. …’ ʿAṭāʾ recommended for her to wear a veil when she prays, but he did not obligate it51Ibn Qudāma, al-Mughnī (Riyadh: Dār ‘Ālam al-Kutub, 1997) vol. 2, pp. 331–332.

Where the legal value of nadb (recommendation) applied to the slave woman, the legal value of obligation (wujūb) applied to the free woman, and they are both positive legal values.

b) The case of Sayyid ʿUmar and the slave girl

Notwithstanding the legal differences between slave and free women, we will explore the incident of Sayyid ʿUmar

The incident between Sayyid ʿUmar and the slave woman is as follows: ʿUmar scolded a slave woman because she dressed in a manner that people would assume she was emancipated. This incident is usually invoked as evidence to explain ‘an yuʾrafna’ (so that they be known) in the verse of jilbāb to mean that their social status may be known as free women.

Although the most common interpretation given by scholars is to be known as free women, the verse’s silence on the matter gave rise to various interpretations on what it was that the women were trying to make known. To give an example of the possible interpretations, al-Rāzī says, ‘it is possible that the meaning of yuʿrafna is to make known that they do not commit adultery (zinā)…52Al-Fakhr al-Rāzi, Tafsīr al-Rāzī, 1st ed., (Beirut:Dār al-Fikr, 1981) vol. 25, p. 231.’ whereas Ibn Ḥayyān al-Andalūsī and al-Saʾdī added that it was to be recognised for their chastity53Abū Ḥayyān al-Andalusi, al-Baḥr al-Muḥīṭ, (Beirut: DKI, 2010) vol. 7, pp. 240–241. al-Sa’dī, p. 672.. These values equally apply to both free and slave women.

The point here is not to obviate from the fact that scholars have interpreted this to mean ‘known as free women’ in the verse of jilbāb but that a probable interpretation (ẓannī) does not have the epistemic weight to dissolve a legal ruling established in a separate verse.

Ibn al-Mundhir, al-Bayhaqī and others have transmitted variant reports of the incident, however, they have diverging accounts of what the slave woman was actually wearing and doing. The variant reports convey different details54 See Suhayb al-Saqqār’s takhrīj of this incident in Jadalliyatul ḥijāb: ḥiwār ʿaqlī fī farḍiyyatil ḥijāb wa inkārihī, (Rawāsikh, 2017) pp. 136–41.

Incident 1: This is narrated from Sayyid Anas

Incident 2: Ibn Abī Shayba transmits a report in which Sayyid Anas said: A slave woman entered upon Sayyid ʿUmar. He was describing her (to sell) to the companions. She had worn a jilbāb which she used to veil herself with (mutaqanniʿatan bihī) with. He asked her: Have you been set free? She replied: No. He said: Then what is with the jilbāb? Remove it from your head. The jilbāb is for the believing free women. She tarried in what he asked her to do. ʿUmar struck the top of her head, which caused the jilbāb to fall from her head56 Ibn Abī Shayba, Muṣannaf Ibn Abī Shayba, 6292 (Riyadh: Maktaba al-Rushd, 2004), vol. 3, p. 540..

Incident 3: ʿAbd al-Razzāq transmits this report in whicʿUmar

In another variant of this version, a slave woman came out of the house of Sayyida Ḥafṣa

What can be understood from the variant reports is that the slave woman was veiled (mutaqanniʿa) and Sayyid Umar did not immediately recognize her, which may mean that her face was covered as the word mutaqanniʿa carries this possibility. Furthermore, the act of loitering around men and causing fitna was pointed out by Sayyid Umar

What (clothing) suffices a slave girl? He replied: We say what ʿUmar has said regarding this, (that is) she will uncover her hair inside the home so her izār and dirʿ suffice her. He said: She will wear part of her dirʿover her head59 ʿAbd al-Razzāq, Muṣannaf 5105.

Furthermore, al-Ḍaḥḥāk and al-Suddī report that both free and slave women were indistinguishable at the time (in Medina) because they would all go out with a headscarf and chemise.60 Wāḥidī, Asbāb al-Nuzūl, p. 132. This goes to show that covering the hair was not an issue, and that slave girls customarily would use part of their clothing to cover their hair.

Nonetheless, Ibn al-Qaṭṭān commented on the incident between Sayyid ʿUmar and the slave woman as inauthentic, stating that it contained nothing more than his condemnation of her for dressing in a way to make others assume she was a free woman.61 Ibn al-Qaṭṭān, Aḥkām al-Naẓar, (Damascus: Dār al-Qalam, 2012) p.230.

It is more disturbing, in fact, when this story is used to portray Sayyid ʿUmar

During ʿUmar’s own reign, men would complain about how he enforced a ban on temporary marriages. In temporary marriages, women were almost always the vulnerable partner. It was ʿUmar

c) The element of harm as the ʿilla for jilbāb

Along with the social status argument, another reason used to explain the ʿilla of the hijab is physical safety. In the verse of jilbāb, God states,

Prophet, tell your wives, your daughters, and believing women to make their jalābībihinna hang low over them so as to be recognised and not insulted (fa lā yuʾdhayn)…’62Qurʾān, Al-Aḥzāb:59

Since the ʿilla, which is taken to be physical safety is no longer applicable, the verse is no longer applicable either.

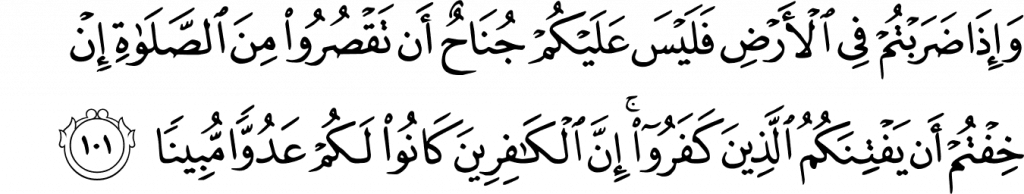

This is problematic because it misunderstands the function of the ʿilla. Firstly, the ruling cannot precede the ʿilla because it is the ʿilla that initiates the ruling. To give an example, the ʿilla for shortening the prayers is ‘travel’ as evidenced from the following verse:

When you go forth journeying in the land, there is no blame on you if you shorten the Prayer..”63 Qurʾān, al-Nisā’: 101.

When a person becomes a traveller, that is, she is in a state of travel, the ʿilla will initiate the ruling of shortening the prayers. Another example is the ʿilla for prayer, which is the time. Once the time enters, the ʿilla initiates the obligation of prayer.

Very simply put, if harm is the ʿilla, it is implying that harm is to take place for the ruling to apply to a woman, which eludes common sense too. Whereas the plain meaning of the verse of lowering the jilbāb, and increasing elusiveness can be used as means towards averting harm. The Qurʾān states,

It is more likely that they will be recognized and not harassed (dhālika adnā an yuʿrafna falā yu’dhayn).

The word adnā in the verse means ‘close to’ (aqrab) or ’means of achieving’, that is, the desired objective.

This kind of expression can be found in other parts of the Qurʾān where God says,

..If you fear that you cannot be equitable [to them], then marry only one, or your slave(s). That is more likely (dhālika adnā) to make you avoid bias.64 Qurʾān, al-Nisā’:3

The objective of the verse is that lowering the jilbāb can be used as a means towards preventing harm, however, it does not mean it will certainly prevent harm. The Qurʾān does not negate nor avert the possibility of harm should a person choose to act it out. In fact, it is affirming that the possibility is always there. Immediately after the verse of jilbāb, God speaks about those immoral people who still do not desist from harming the believing women. He gives a severe warning that He will rouse the blessed Prophet against them until they are driven out of Medina.65Quran, Aḥzāb:60.

The argument also presupposes that the only relevant interest of the Sharīʿa for covering the ʿawra is physical safety, which runs contrary to the exhortations of covering the ʿawra being paired with ‘lowering the gaze’66 Quran, al-Nūr, 24:31 and ‘guarding the private parts’67 Ibid., as a means of ‘purification’68Quran, al-Nūr:30, ‘seeking chastity,’ as well as defining legal parameters of what women can expose in front of their maḥārim.69al-Nūr: 31. The maḥārim are those members forbidden to marry.

Notwithstanding this, the Sharīʿa does recognize situations where the element of harm allows for concession (rukhṣa). However, if the concession given by the Sharīʿa is used to justify the covering of the hair as unnecessary, then it is important to understand the role of a concession and a norm. The principle of concession is derived from the following verse,

He has only forbidden you carrion, blood, pig’s meat, and animals over which any name other than God’s has been invoked. But if anyone is forced to eat such things by hunger, rather than desire or excess, he commits no sin. God is most merciful and forgiving.70Quran 2:173, translation by Abdel Haleem.

The norms of the Sharīʿa may be temporarily suspended under exceptional circumstances. However, the concession does not change the legal value of the norm. In other words, concessions (rukhaṣ) for exceptional circumstances cannot nullify legal norms because they are relative to the legal norms. If the legal norm does not exist, neither does the concession. The legal value of covering the hair is obligation (fardh), and whether harm occurs or not, the value remains.

d) Fitna and ʿawra

The second objection of the negationists is related to fitna. The term fitna is multifaceted. In the Qurʿan, it has come to mean ‘persecution’, ‘physical affliction’, ‘dissension’, ‘trial’ and ‘temptation.’ With regard to the ʿawra, the issue particularly focuses on fitna to mean sexual temptation, which leads to committing sin.

The ‘awra is covered not because of fitna, but because of a command from God. It is to be covered even if it does not cause fitna, and it is possible that fitna can arise from things that are not necessarily part of the ʿawra.Click To TweetCovering the ʿawra is an obligation qua obligation. The ‘awra is covered not because of fitna, but because of a command from God. It is to be covered even if it does not cause fitna, and it is possible that fitna can arise from things that are not necessarily part of the ʿawra. When jurists discuss the legal parameters of the ‘awra, they did not use fitna as a rationale to justify the obligation. In fact, when God speaks of the immoral behaviour of the hypocrites and the fitna they caused, they were condemned for their actions and not the victims of their assault.71 Qur’ān, Aḥzāb:58–60. Reportedly these verses were revealed in response to several incidents in which the hypocrites of Medina harassed Muslim women. In Islam, no one is culpable for the actions of another, and each person will have to answer for their own actions.

This principle is not so much a justification as it is a warning to take ourselves into account. Just as covering the ʿawra is a core value of the outward form, so is its complementary value of the inward form, ḥayāʾ (modesty). The blessed Prophet

In addition to the legal parameters of the ʿawra, its normative practice as embodied in the value of modesty is found in the prophetic Sunnah and the practice of the prophetic community.

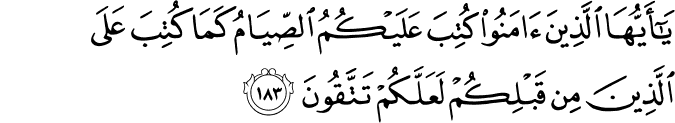

Values complement one another because legal obligations have a physical and spiritual dimension for the very reason that our existence is predicated on the body and the soul. The Qurʾān states,

O you who believe, fasting is prescribed for you — as it was prescribed for those before you — so that you may achieve taqwā.74Qurʾān, 2:183.

There is no spirituality without the law because God’s commands can only be recognized through the prescriptions outlined in jurisprudence. There is no jurisprudence without spirituality because actions are unacceptable without purifying the intention. The perfection of the human body can only occur with the perfection of the human soul.

The purpose of our physical worship is to achieve awareness of God (taqwā), and this form of awareness is inextricably connected to the soul. God states,

And by the soul and the One who fashioned it.

Then with the knowledge of right and wrong inspired it!

Successful indeed is the one who purifies it,

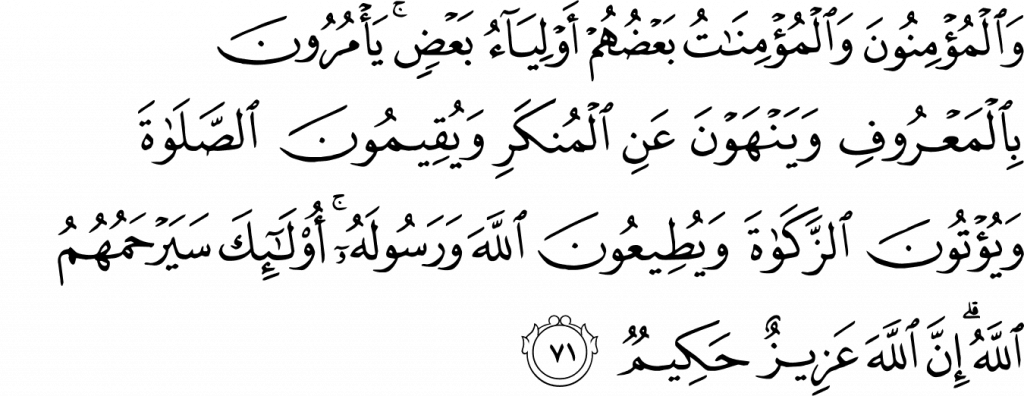

and doomed is the one who corrupts it!75 Qurʾān, Taubah:71

Al-‘Attās elaborates, ‘the human body and the world of sense and sensible experiences provide the soul with a school for its training to know God.’76al-Attās, Prolegomena to the Metaphysics of Islam. (Kuala Lumpur: International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization,1995) p.175 Salvation is dependent on the process of purifying the soul, which signifies the impact of our physical actions, our good deeds and misdeeds, on our spiritual state.

The separation of values from one another also creates an ‘either… or’ situation. To illustrate, negationists make the poor argument that surely the chest is more sexually arousing than the hair. Notwithstanding the foregoing discussion on fitna, and the plainly differing standards of what people find sexually arousing in various cultures, the chest was always part of the ‘awra in conjunction with covering the hair (.. and..). It was never an exclusive ‘either.. or..’ matter.

Altogether, the prophetic code of practice creates a healthy society that prioritizes substance of character over physical form, curing the unhealthy obsessions around the latter. It focuses on the interdependent actions men and women create together to build entire social structures where they are, as the Qurʾān describes, allies to one another.77Qurʾān, Al-Shams:7–10.

Conceptual issues: the historicization of the Qurʾān as a methodological approach

A historicist approach views the Qurʾān as a product of its socio-historical milieu. This means that the Qurʾān is specific to the blessed Prophet’s

Although, it can equally be argued that understanding of the ruling of khimār in the context of its revelation is a postmodernist approach, however, the hermeneutical frameworks are completely disparate in the fundamental principles they rest upon, even if the tools they may employ are similar in some regard. As explained previously with the thawābit and the mutaghayyirāt, socio-historical contexts are only considered in so much as they inform our understanding of how rulings are contextualised, not in determining their truth-values.

It should be pointed out that some postmodernist scholars who use historicization as a methodological approach claim that that the ethical-moral terms in the Qurʾān are specific to Arab society but then hasten to suggest that one can infer universal moral laws from the Qurʾān.80 Barlas, The believing women in Islam, p.59. The question is, how does one justify the process of rationally inferring a universal law rather than another if the Qurʾān is simply a product of its socio-historical context? Notwithstanding the point that the values underpinning the very process of their inquiry is left in the dark. In fact, the very term ‘universal law’ is antithetical to postmodern philosophy. Universal laws, accordingly, are no more than a shared set of values and ideals of the group in a position of power to assert them (this idea itself is not immune from the very same critique it applies, in that truth claims serve the demands of power). Instead, the domination of popular morality stands in for a set of universal moral standards. To give an example, when Muslim women choose to embody the moral values of their faith and not Western ideals of sexual freedom and choice, the Western feminist cannot comprehend why Muslim women do not want what they want. Surely, Muslim women must be saved from their oppressive religion, by force of arms if necessary.

As for the historicization of the Qurʾān, the consequence of this methodology is that one can go so far as to deconstruct the fundamental blocks of Islam itself. This can already be seen in postmodernist writings where the very concept of God, His essence and attributes are replaced with terms like ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy.81Hasan Hanafi, al-Turāth wa al-Tajdīd (Beirut: Dār al-Tanwīr, 1980) p.103.’

This methodological approach severs the divine nature of the Qurʾān, as arising from human experience to no meaningful conception about God, rather than divine knowledge descending from God, as Lawmaker, to change human condition by providing a set of moral values grounded in a transcendental source.82Knowing about God is different to knowing God in Himself. Positive attributes (asmā al-ḥusnā) about God are known through the effects of the acts of God. For example, we know God is Creator because there is a creation. At the same time, as the Infinite, He is unknowable in Himself because He will always be infinitely more. The consequence of the formers’ view is that moral values are relativised to ever changing socio-historical contexts and interpretation is dependent on the socially constructed schemes of morality of each interpreter.

But the idea that the moral code of the Qurʾān is a social construct is itself a social construct, as it lays claim on how the world works or how reality is. The claim, however, is not any real as its constructor nor anything existing independently of its constructor. The Qurʾān as God’s address to man, and as an expression of reality, means socio-historical conventions do not determine the divine law, rather, the divine law determines them as is evident in God’s qualifying of the khimār.

Postmodernist scholars that historicize the Qurʾān as an end in itself intend by it to free people from the divine authority and sovereignty of Qurʾān.83 For example, Nasr Hamid Abu Zaid, al-Imām al-Shāfi’ī wa ta’sīs al-āidulūjiyya al-wasaṭiyya, 3rd ed. (Cairo: Madbūlī, 2003), p.15, Arkoun, “Rethinking Islam Today,” p.211, Ḥasan Hanafi, Al-Turāth, p.45. See Auda in Maqāṣid al-Sharī’a asPhilosophy of Islamic Law: a systems approach (The international institute of Islamic thought, 2007) p. 182. This is hardly surprising because postmodernist culture is characterised by the shift of sovereignty to the individual in a way where it affirms and ironically denies it too. It denies it in the sense that an individual can never transcend their structure of thought as reason itself is a conceptual construct. This is why it views revelation as only applicable to its socio-historical context. At the same time, the sovereignty is placed on the individual whereby she should pursue her personal set of ideas and values, which are her personal truths. She is free to define herself as she chooses because other truths cannot claim authority in relation to her truths. But all these truths will perish before the face of al-Ḥaqq, the absolute Truth, who gave us recognition of ṣirāṭ al-mustaqīm, the one path of Truth.

When the lines between exegesis and eisegesis have become blurred, revelation is no longer approached to uncover God’s intent but to deconstruct the very concept of God and belief. This results in an epistemological vacuum that is filled with the individual’s personal set of ideas for them. A person can equally choose to wear and remove her hijab using the same claim of personal choice.

But God is not a mere interpretive construct, and we are not free to define ourselves as we choose. One of the greatest opressions creation can commit is to take the place of Creator and define herself with an image of her own making. The word ẓulm precisely is to place something out of its place.

The purpose of human existence is predicated on worship, and God gave us revelation in order that we may achieve our purpose. So while people will do things that may coincide with revelatory commands, what changes the moral status of those acts is the purposes behind them.

The proclamation of lā ilāha — there is no god — is to annihilate those gods in the images of our desires, our personal truths, or even ourselves. Those weighty words annihilate all to prepare the heart for illallāh — but God. Our master Rūmī explained,

After no god, what remains? Nothing remains but God –Allah– the rest has gone.

Acknowledgements: I am very grateful to the following Shuyūkh who took the time to read through the paper, offered constructive feedback and provided valuable support; Shaykha Mariam Bashar — to whom I am incredibly grateful — Shaykha Shazia Ahmad, Shaykha Maryam Amir, Dr Mansur and Imam Hassan.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Sh. Marzuqa holds a shahāda ʿālimiyya from Ebrahim College and an MA in Islamic Studies from SOAS. She has studied with, and obtained ijāzāt from Shaykh Akram Nadwi (Al-Salam) and Shaykh Hatim al-Awni (Umm al-Qura). Her interests are Islamic jurisprudence, ethics and theology.

The Sikh – A Ramadan Short Story

When Islam Feels Like A Burden | Night 19 with the Qur’an

The Art of Tadabbur: Enriching Our Relationship With The Quran

Why Do Bad Things Happen to Good People? | Night 18 with the Qur’an

Revolutionary Philosopher And Potentate: The Life And Polarizing Legacy Of Ali Khamenei

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

Where Does Your Dollar Go? – How We Can Avoid Another Beydoun Controversy

An Unending Grief: Uyghurs And Ramadan Under Chinese Occupation

Who Am I Really? What Surat Al-‘Asr Teaches Muslim Teens About Identity | Night 1 with the Qur’an

Ramadan In The Quiet Moments: The Spiritual Power Of What We Don’t Do

Why Do Bad Things Happen to Good People? | Night 18 with the Qur’an

Is Depression a Lack of Faith? A Guide for Muslim Parents | Night 17 with the Qur’an

I Can’t Feel Anything in Prayer – Understanding Spiritual Dryness | Night 16 with the Qur’an

Every Sin Has a Cure | The Venom and the Serum Series

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Someone | Night 10 with the Qur’an

Trending

-

#Islam3 weeks ago

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

-

#Life1 month ago

[Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy

-

#Islam1 month ago

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

-

#Islam1 month ago

[Podcast] Guardians of the Tradition: Muslim Women & Islamic Education | Anse Tamara Gray

Abrar

May 12, 2022 at 3:39 AM

asalamualaikum. Thank you for writing this article. I was especially happy with your take on the slave woman’s legal status when compared to a free woman. There is however a discrepancy between scholars in regards to a their awrah. Particularly, many are of the opinion that the prophet peace be upon him had delineated the awrah to be from the navel to the knees such that when the master wishes to marry off the slave woman he can look everywhere besides those areas. Id like to know your thoughts on this and its implications on public morality since you have mentioned veiling was reccomended but not obligatory for the slave girl.