#Culture

200 Years Of Orientalism: From Mary Shelley To Khaled Hosseini

Published

Intro

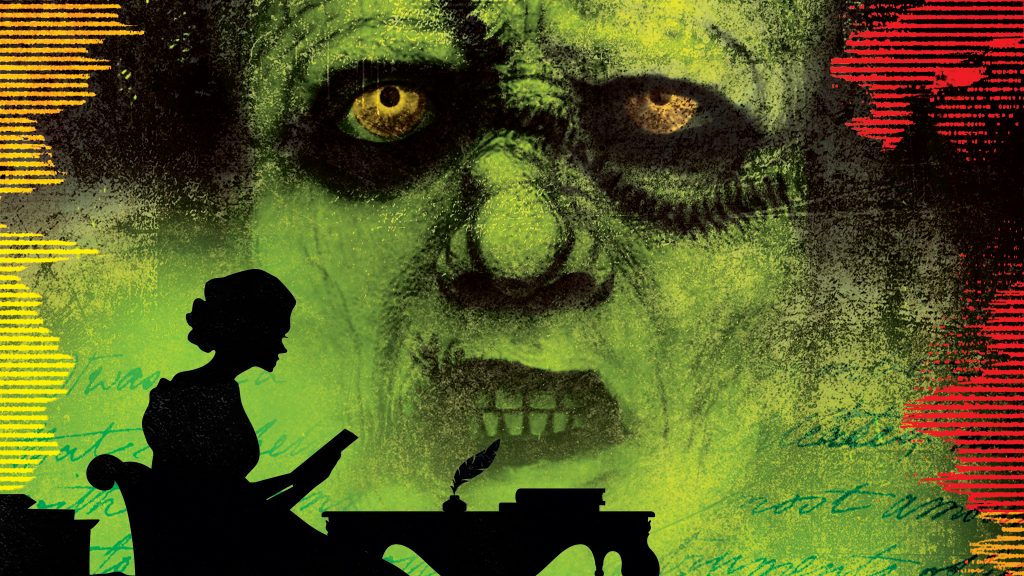

Back in October, I decided that the dreary weather and shorter daylight hours called for a comfort read. Lately I’ve found that the best comfort can be found in classic novels. One classic that kept popping up in my bookstagram feed at the time was Frankenstein; since I already had a copy, I decided to give it a try.

The book was alright. It wasn’t really the comfort I had hoped for—it really is as bleak and depressing as everyone says it is—but I did enjoy drifting among the poignant descriptions of the Swiss mountains and natural landscapes.

But then: bam, right in the middle of the book, I’m hit by a dose of pure, unadulterated Orientalism.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

The following conversation is about Safie, a young Arab-Turkish woman visiting a European family, whom the Frankenstein monster was observing:

“Safie related that her mother was a Christian Arab, seized and made a slave by the Turks; recommended by her beauty, she had won the heart of the father of Safie, who married her. The young girl spoke in high and enthusiastic terms of her mother, who, born in freedom, spurned the bondage to which she was reduced. She instructed her daughter in the tenets of her religion and taught her to aspire to higher powers of intellect and an independence of spirit forbidden to the female followers of Muhammad. The lady died, but her lessons were indelibly impressed on the mind of Safie, who sickened at the prospect of again returning to Asia and being immured within the walls of a harem, allowed only to occupy herself with infantile amusements, ill-suited to the temper of her soul, now accustomed to grand ideas and a noble emulation of virtue. The prospect of marrying a Christian and remaining in a country where women were allowed to take a rank in society was enchanting to her.”1Mary Wollstonecraft-Shelley, Frankenstein, 1818, chap. 14.

I was quite shocked. The whole story was set in Switzerland and England up to this point, and it was already far-fetched that an Arab-Turkish woman should happen to make an appearance, let alone be used as an icon to spur women’s rights.

But then, looking back, I suppose I shouldn’t have been so surprised. The book is a “classic,” right? And doesn’t that mean it was written during the heights of British colonialism? Of course it would be natural for those ideas of British (and Christian) superiority to leak into the literature at the time. Edward Said wouldn’t have written Orientalism2Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978). otherwise!

I got over my initial discomfort and continued reading, only to realize that neither the quote in question—nor the characters involved in it—had any effect on the rest of the plot. This paragraph could literally be removed, and nothing else in the rest of the story would’ve been different. It was just there for the sake of being there; for the sake of victimizing the “Eastern” woman and villainizing the “Eastern” man who enforces the oppressive veil upon her.

White Feminism vs. Oppressed Muslim Women

Wollstonecraft’s work as a British feminist was rife with demands for women to be given their “rights,” reasoning that otherwise, British society would be comparable to Eastern society. “In the true style of Mahometanism,” she says, “they are treated as a kind of subordinate beings, and not as a part of the human species,” and so if England were to resemble this in anyway, they would be falling into the “true style of Mahometanism,” which is what British society must attempt to distance itself from at all costs3Mary Wollstonecraft, “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.” http://pinkmonkey.com/dl/library1/vindicat.pdf.

For these Western feminists, the Eastern woman was both a victim and a warning: if women were not given their rights, Western society would degenerate into adopting inferior Eastern traits.

So, literary representations of Eastern women as oppressed victims were used to promote the call for women’s rights in England so as to reinforce British superiority above the east and to justify colonial intervention.

The Family-Political Complex in Colonialist Policy

Feminism was not the only sphere in which an attitude of superiority in Western family practices existed. It also existed in colonial policies, and shaped the ways that colonized peoples perceived themselves.

As a case study, Lisa Pollard (a historian specialized in the modern Middle East) examines how perceptions on domestic practices in Egypt shaped both colonial rule and the anti-colonial Egyptian response to it. Pollard argues that “Egyptian domestic practices—both real and imagined—were used not only to fashion the policies through which the British ruled Egypt but to justify their open-ended tenure there.4Lisa Pollard, Nurturing the Nation: The Family Politics of Modernizing, Colonizing, and Liberating Egypt, 1805-1923 (University of California Press, 2005), 13. ” The British reasoned that because of the Egyptians’ “strange” and domestic habits, Egyptians were inferior and therefore unfit to rule themselves.

In response, the Egyptian nationalist movement -in order to gain independence from the British in the early 1900s- promoted a change in domestic dynamics; a demand that fit in nicely with Egyptian women’s activist movements at the time and helped shape nationalist identities. By changing domestic norms to be more consistent with hegemonic British ideas, colonized people -not just in Egypt but in other predominantly Muslim countries-, often tried to improve their image in the European perspective to shed off the inferiority ascribed to them.

Pollard argues that by adopting European attitudes towards women, the Egyptians (at least the elite, upper classes who led women’s rights movements) hoped to be considered more civilized, have a better sense of nationalism, and be better prepared to oust the British and gain political autonomy.

So, the victimization of Eastern women in European literature didn’t only serve to justify colonial policies—it had the effect of changing the ways colonized people view themselves, of believing in their inferiority to British hegemonic culture.

Moreover, the idea of copying European practices in order to advance one’s own society was not limited to the colonized Egyptians, nor specifically to the treatment of women; several anti-colonial reform movements adopted this strategy into various social aspects: like education, industrialization, and government policy.

Orientalist Literature Today

Orientalist portrayals of women—especially women with a Muslim background—are unfortunately not limited to classics or books written during the colonial era. Nor are they limited to books written by non-Muslims.

Personally, I used to consider The Kite Runner and A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khaled Hosseini as my favorite books when I read them a few years ago—probably because as a teen, they were the first and only novels I was exposed to that had complex Muslim characters, and took place in a predominantly Muslim country. But more recently, when I read of some Muslim bookstagrammers and journalists pointing out their Orientalist tendencies (and after recovering from my initial denial), I decided to go back and examine these stories more closely.

Even when I perused these novels a second time, I had to admit that Hosseini has a skill in tugging at the readers’ sympathy for the oppression that his characters go through. And I won’t deny that his depiction of bleak circumstances in Afghanistan do at least partially shed light upon struggles Afghans—especially Afghan women—may face. But the issue was that, unlike the first time I read the books, I realized the second time all the little references that justify US military intervention and imperialism.

The suffering that Hosseini’s characters—specifically the Afghan women—go through serves a purpose in the narratives. While these experiences may be valid and should not be silenced, it is both unfair and dangerous to use these narratives to validate Western intervention, even if implicitly.

I’m not saying these women are not oppressed, nor that their stories should not be told. I’m saying that whatever their experiences are (whether they’re oppressed or not), they’re often twisted into a narrative for a western audience in order to provoke a sense of pity for them (victimizing almost all the women characters and villainizing the “religious” men) in order to justify a western agenda—whether the agenda is women’s rights in Shelley’s case or US military intervention in Hosseini’s.

Hosseini’s novels became a type of “single-story” as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie explained in her famous TED-Talk. The bleak circumstances and the sense of relief that came from American intervention became the only and ultimate reality of disadvantaged Afghans in the minds of the Western audience that knows few, if any, alternative narratives on Afghanistan.

These portrayals only serve to harm these very women instead of uplift them, continuing the centuries-old narrative of Western superiority and white saviorhood. Just as the depiction of the victimized Eastern woman became used as an excuse for imperial intervention in colonial times, Hosseini’s same depiction also became used to justify American intervention in Afghanistan—a new aspect of the same old story of Western imperialism.

And unfortunately, Hosseini is not alone—neither as an author, nor as a Muslim author—in continuing to use portrayals of victimized Muslim women as tools for imperialist propaganda.

Conclusion

Because fiction has such a huge impact on our identities, it is important to consider it with a critical lens. Fiction must be examined carefully, for both the explicit and the implicit messages a piece has to offer.

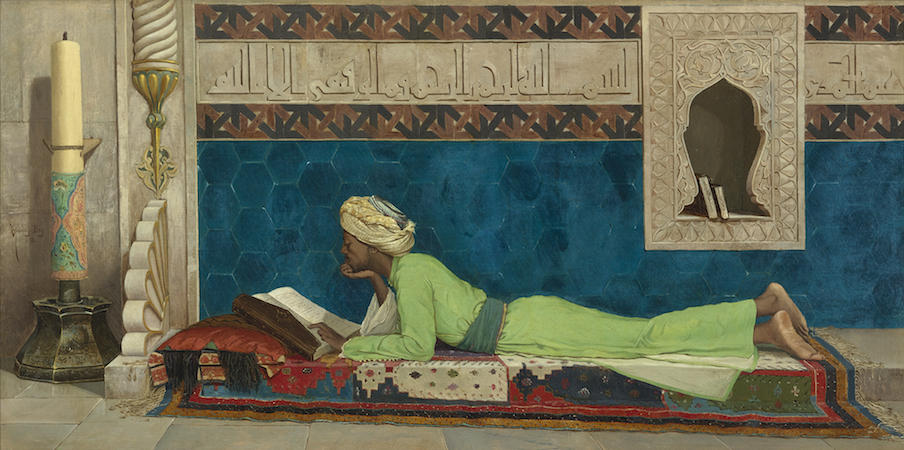

For centuries, Orientalism in art and literature has shaped the presentation of Muslim women to the Western gaze.

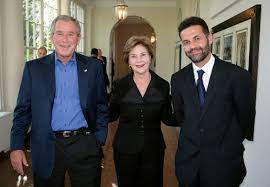

Depictions of oppressed Muslim women in art are often orientalist tools to emphasize the superiority of the colonizer and provide justification for their policies. It is little wonder, then, that these depictions often receive high praise from those who benefit from the idea of Western superiority and imperialism–for example, Laura Bush praising Hosseini’s novels.

On the flip side, we can see how it shaped the identities of colonized people, leading to internalized inferiority; as in how early 1900s Egyptian activists aimed to change domestic practices to themselves to their British colonial overlords.

This threat of orientalist narratives upon our identities has not disappeared: it still exists today, and sometimes, unfortunately from Muslim authors themselves.

When trying to uplift the voices of oppressed women–or, more broadly, any disadvantaged people–we must be careful not to turn their narratives into single stories, or to imply that their entire religious and cultural backgrounds are to blame for their circumstances. Moreover, their stories should not be used to justify foreign imperialist intervention and exploitation.

As Muslims, we must critically evaluate these works, call them out publicly, and push for more authentic, nuanced, and anti-orientalist narratives.

Related articles:

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Ayah is a graduate student in World History and Digital Humanities. She hopes to combine her background in software and love for history and storytelling to make historical stories more accessible to diverse audiences. She also loves teaching Quran to children in her community. You can find her bookstagram @caveofkutub.

Can You Give Zakah to Politicians? A Round-Up

Doubt, Depression, Grief, Shame, Addiction: Week 3 Recap | Night 21 with the Qur’an

She Cried At The Door Of The Masjid: A Case For Children In Mosques

I’m Addicted and I Can’t Stop | Night 20 with the Qur’an

The Sikh – A Ramadan Short Story

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

Where Does Your Dollar Go? – How We Can Avoid Another Beydoun Controversy

An Unending Grief: Uyghurs And Ramadan Under Chinese Occupation

Who Am I Really? What Surat Al-‘Asr Teaches Muslim Teens About Identity | Night 1 with the Qur’an

[Podcast] Ramadan Is Not For Your Private Spirituality | Dr Farah El-Sharif

Doubt, Depression, Grief, Shame, Addiction: Week 3 Recap | Night 21 with the Qur’an

I’m Addicted and I Can’t Stop | Night 20 with the Qur’an

Why Do Bad Things Happen to Good People? | Night 18 with the Qur’an

Is Depression a Lack of Faith? A Guide for Muslim Parents | Night 17 with the Qur’an

I Can’t Feel Anything in Prayer – Understanding Spiritual Dryness | Night 16 with the Qur’an

MuslimMatters NewsLetter in Your Inbox

Sign up below to get started

Trending

-

#Islam3 weeks ago

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

-

#Society3 weeks ago

Where Does Your Dollar Go? – How We Can Avoid Another Beydoun Controversy

-

#Islam1 month ago

[Podcast] Guardians of the Tradition: Muslim Women & Islamic Education | Anse Tamara Gray

-

#Current Affairs3 weeks ago

An Unending Grief: Uyghurs And Ramadan Under Chinese Occupation

Malahat

January 17, 2022 at 10:39 AM

Thanks for the informative article. The documentary Reel Bad Arabs went into detail about how there were a lot of instances like this in film as well.

Aisha

January 17, 2022 at 12:48 PM

Hello Sister Zainab,

This was an excellent piece. It very much reminds me of the controversy surrounding To Kill a Mockingbird where people pointed out that the novel was racist b/c it portrayed a black victim of a white lynch mob as needing to be saved by a white liberal lawyer set in the American south. But at least that was a controversy that made into the mainstream media. Have you ever read any of Leila aboulella’s novels? I think her novels make a really good antidote to the problems that you describe with Orientalist fiction.

Zainab bint Younus

January 17, 2022 at 2:03 PM

Salaam! This excellent article was written by the awesome sister Ayah Aboelela :)

Yes, Leila Aboulela’s writings are amazing mashaAllah! She is one of the few mainstream published Muslim writers who pushes back against the internalized Islamophobic narratives that dominate, unfortunately.

Aisha

January 19, 2022 at 1:13 PM

araheel6@gmail.com

Hello Sister Zainab,

I thought you wrote this article. I thought I saw your byline, and didn’t that Leila Aboulela had written it! My bad.

Nusar Milbes

February 5, 2022 at 9:51 PM

Deepa Kumar calls it Imperialist Feminism.