#Life

How To Respond To Suicide In Muslim Communities

Published

By Rania Awaad, MD, Taimur Kouser, Osama El-Gabalawy, MS

Trigger Warning: This article discusses suicide which some might find disturbing. If you or someone you know is having serious thoughts of suicide, please call 911 or the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Mental health is an important part of our Islamic tradition, history, and legacy. Nevertheless, mental illness remains a greatly stigmatized topic in Muslim communities. Like people of all faiths and backgrounds, Muslims experience mental health challenges, mental illnesses, and indeed suicidal ideation. Nonetheless, Muslims tend to particularly stigmatize suicide. Islam teaches us about the value of human life as well as the certainty of hardships and trials in this world, and it clearly prohibits people from killing themselves. Despite these teachings, the reality is that many Muslims in the United States and around the world struggle with thoughts of killing themselves, and many Muslims do die by suicide. Contrary to common belief among Muslims, faith and prayer alone do not make a person immune to depression, thoughts of self-harm, or suicide. When a death by suicide does occur in a Muslim community, we must turn to Islamically grounded and scientifically sound principles on how to respond.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

It is imperative to first understand a few definitions:

- Prevention are the steps taken to reduce the risk of suicide. However, in the aftermath of a suicide, our focus should be on postvention and community healing.

- Intervention relates to the direct effort to prevent a person from taking their own life

- Postvention are the steps people take to respond to a suicide after it happens. These strategies emphasize the need to save life and help ensure that community members have access to appropriate mental health care services. After a suicide happens in a community, mental health professionals shift their focus to preventing suicide contagion.

- Suicide contagion is a well-documented phenomenon in which people’s direct or indirect exposure to suicide increases their risk of dying by suicide too. Suicide contagion can result in suicide clusters.

- Suicide clusters are when multiple suicides occur in close proximity.

Preventing suicide contagion is one of the top priorities of a postvention response. Community leaders and community members can all take steps together to prevent additional suicides and support healthy patterns of communal grieving and healing.

10 Do’s and Do Not’s to Follow after a Suicide Occurs:

1. DO NOT sensationalize or romanticize suicide

First and foremost, when a suicide occurs, it is critical NOT to sensationalize or romanticize the death. Talking about the location of death, means of death, and specific details of a recent suicide are harmful discussions and should be avoided. These details, although reported in good faith, often sensationalize or dramatize the tragedy that has occurred. Suicide contagion spreads by people and media outlets sharing unfiltered content on suicide with little to no mention of resources for help. It is an especially big concern in today’s world because of how easily things are shared on social media.

Concrete actions to avoid include:

● NOT re-posting or discussing suicide notes

● NOT sharing details of a specific suicide case

● NOT discussing the victim’s circumstances

● NOT romanticizing the death as a solution to what he or she was going through.

Why? Because people who are struggling with serious thoughts of killing themselves may identify with parts of these conversations which may motivate them to make an attempt on their own life. It is vital to NOT contribute to any narratives that normalize or sensationalize suicidal behaviors. Anything that is shared or discussed should focus on hope, healing, and offer support and resources for those who are struggling.

2. DO NOT speculate or dwell on specifics

Suicide is an immense tragedy, and it is very common to try to make sense of and understand what exactly occurred. Dwelling on details of a suicide, speculating on unsubstantiated reports, or engaging in gossip do not contribute meaningfully to the healing or the grieving process. For healing to occur during the aftermath of suicide, one must recognize that questions will remain unanswered and do not need to be answered. Investigating the details of the case should be left to the authorities and mental health experts. As authorities release details of the case, it is imperative not to dwell on the specifics of the case. Spending a significant amount of time analyzing details can serve as a barrier to processing emotions and grieving in a healthy manner.

3. DO NOT speculate on the spiritual implications of suicide

Suicide is clearly prohibited in Islam. This means that many people begin to think about the spiritual implications for someone who has died by suicide. Do they get the janaza prayer? Will they be able to enter jannah? Are they still Muslim? Although it is understandable why people have these questions, it is imperative to remember that Allah (SWT) is the ultimate judge of what happens to all of us, no matter who we are, what we have done, or how we die. Additionally, we may not know all of the factors that contribute to a person who dies by suicide. People in a suicidal state often have distorted thought processes and pre-existing mental illnesses are implicated in over 90% of suicide cases. For these reasons, speculating on the spiritual implications for someone who dies by suicide is useless and extends beyond the capacity of human beings. The community needs to focus on healing and responding to a suicide, not on making judgements or assessments of matters that we will never know with certainty.

4. DO NOT try to diagnose a person who died by suicide

There are multiple factors that contribute to suicidal ideation and behavior. Risk factors for suicide can include biological factors (like a person’s genetic makeup or brain chemistry), psychological factors (like the presence of other mental illnesses), social factors (like how connected and supported people feel with their families and friends or how much stress they feel in a given time period), and even spiritual factors (like how people think about Allah). There is truly no way to know which of these factors may have caused a person to kill themselves just by reading a suicide note they have left behind or analyzing aspects of the person’s life. For that reason, it is important to NOT diagnose a person who has died by suicide. Moreover, trying to do so can be harmful for the community, jarring for the family, and distracts from what should be the main focus in the aftermath of a suicide – grieving, supporting, and healing. Ibn Umar reported: The Messenger of Allah, peace and blessings be upon him, said, “Mention what is good about your dead, and refrain from speaking about their evil.” (Sunan al-Tirmidhī 1019)

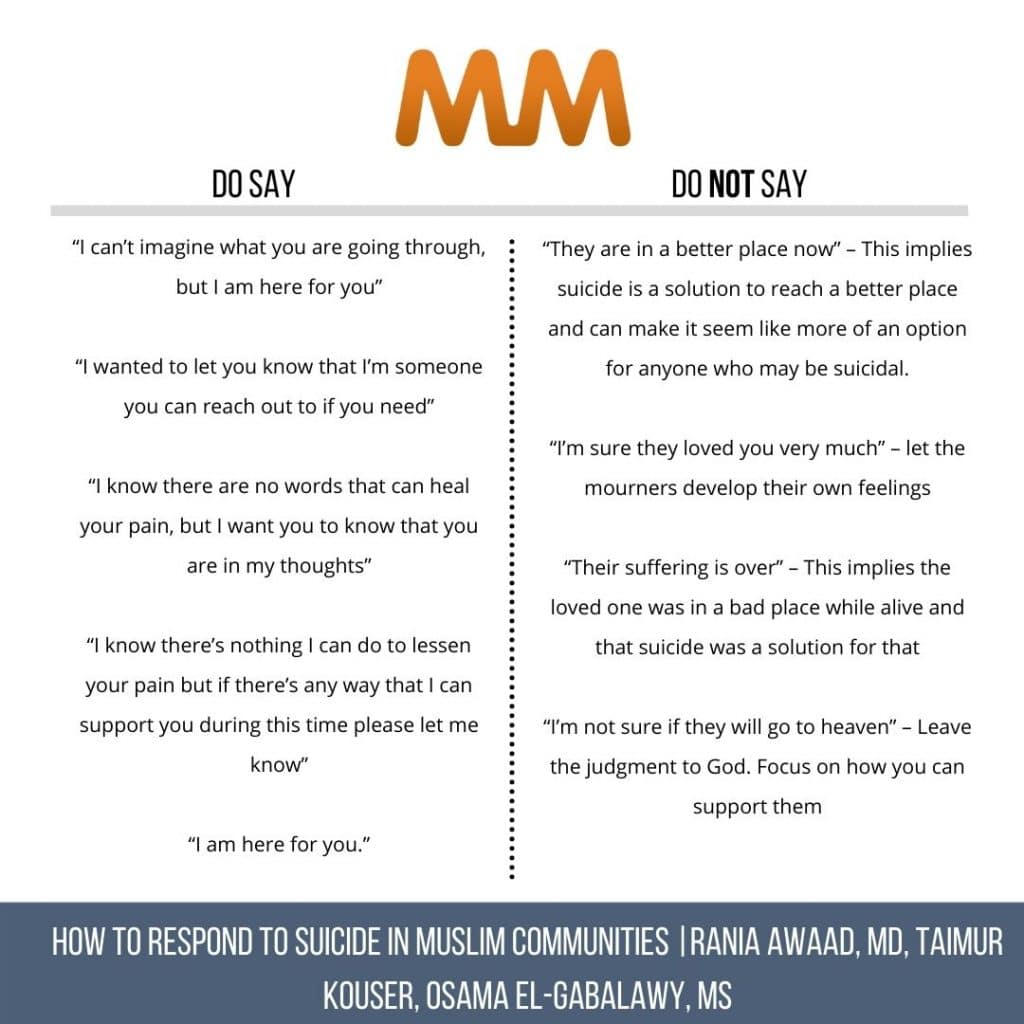

5. What TO say and NOT to say when consoling someone who is grieving

Many times it is challenging to find the correct words to say to those who are grieving the loss of someone who dies by suicide. When you meet a loss survivor, someone bereaved by the suicide of a loved one, express sympathy as you would for any sudden death. Those close to the victim may grapple with a range of complex emotions such as grief, fear, shame, and anger. Let them lead the conversation and be compassionate when listening and responding. Remember to listen to the emotions that they are sharing with you and respond to the emotions you hear rather than to your own feelings.

When Sayida Zainab’s son, may Allah be pleased with them both, was dying, she called for her father, the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him. As the Prophet saw his grandson struggle with his last breaths, the Prophet’s eyes streamed with tears. Sa’d bin ‘Ubadah said “O Messenger of Allah! What is this?” Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, replied, “It is compassion which Allah has placed in the hearts of His servants, Allah is compassionate only to those among His servants who are compassionate (to others)”

Here is a brief list of ways on how to console someone who is grieving:

6. DO NOT blame each other and DO NOT blame yourself

Blame and the notion of “who is responsible” are common feelings that come up when someone dies by suicide. Some people (like close family and friends) may wonder why they did not catch the signs that their loved one was thinking about killing themselves. Others may wonder whether they could have stepped in or intervened in some way. Community leaders may be concerned about the state of their community and wonder whether they could have implemented better programs, while community members may be frustrated that better programming and support systems were not in place. Although these feelings are valid and understandable, it is crucial that people do not blame each other or themselves. Once someone has died by suicide, the focus needs to be on grieving and healing, and assigning blame does not help with either. In the long-term, the community can begin to take steps to implement new mental health programming in a constructive way.

7. DO process emotions

Humans are emotional creatures. Our thoughts, action, and behaviors are intimately linked. Our lives are marked by sadness, happiness, joy, anger, frustration, grief, and more. Intense events like the death of a community member by suicide can trigger intense emotions in all of us, but the emotions that are triggered may not be the same for each person. Some may feel sadness, while others may feel anger. Some may feel numb, and others may feel a combination of emotions. To heal in these situations, it is imperative to process the emotions that we ourselves are feeling and make space for others to process in a way that feels right for them. Processing these emotions helps us make sense of the events around us and enables us to help others heal too. There are many Qur’anic verses and Hadith that inform us how to cope with grief and how to support those who are grieving.

8. DO reach out to each other and check on each other

Every single person can play a vital role in creating a mentally healthy environment through thoughtful gestures, no matter how large or small. In the aftermath of a suicide, communities can organize to support loss survivors not only by lending an open ear, but also by providing different types of support during the grieving process. Organizing a meal train, offering to babysit, or even buying flowers are very thoughtful gestures that can have a meaningful impact. Before doing any of this, however, it is important to ask what is desired and needed by those who are grieving, and allow for them to respectfully decline. Some may desire to be left alone, and that is okay, but one should still ask and offer support. It is also just as important to regularly re-assess any new or changing needs.

More broadly, checking-in consistently, both in the short term and long term, with anyone particularly impacted by the suicide or anyone struggling with mental health in the community is key to suicide prevention. Friends and family are often the first to recognize if something is wrong, and can play an integral role with linking one to professional help. When people are willing to listen to each other and to support each other, the entire community becomes stronger and tight-knit.

9. DO identify ways for community members to seek religious and professional support

DO identify ways for community members to seek religious and professional support Click To TweetFollowing any death, including a death by suicide, community members will need to grieve and heal. It is important to realize that different types of experiences can require different forms of help. People should first identify whom they resonate most with– a religious leader, a local counselor, a Muslim mental health professional, or a non-Muslim mental health professional. They can then find a list of providers for the type of help they are seeking and take initiative to reach out. To help someone else who is struggling, people should also try to identify the best form of professional help and refer their friend there. Religious leaders are usually best equipped to address crises of faith and offer spiritual, non-professional counseling. Whereas mental health professionals like psychiatrists, psychologists, professional counselors, therapists, and social workers are better equipped to help people with their experiences of mental illness. Religious and professional mental health support are both important and necessary. The key is to seek the right type of care for the appropriate problems and to escalate care to a mental health professional or emergency services (i.e. 911) when in doubt.

10. DO remember that suicide is preventable, mental illness is treatable, and these challenging times are surmountable

It is imperative to understand and to keep in mind that suicide is preventable and that mental illness is treatable. When we affirm these values and truly take them to heart, it can help empower us to take steps to prevent suicides from happening in the first place. Prevention strategies refer to steps that communities can take to prevent suicidal crises from happening in the first place. These strategies include community-level actions, as well as individual-level actions. Just as we strive to develop healthy Islamic environments for our children and our loved ones, we must also strive to create environments that promote and support mental health.

Some steps that Muslim community leaders can take in the long-term include: establishing relationships with local mental health professionals, creating and hosting frequent mental health education and awareness events in community spaces like schools and mosques, and even developing and maintaining support systems such as a local Muslim mental health community advisory board (CAB) and crisis response team (CRT) that are dedicated to promoting mental health and wellbeing in the community.

Conclusion

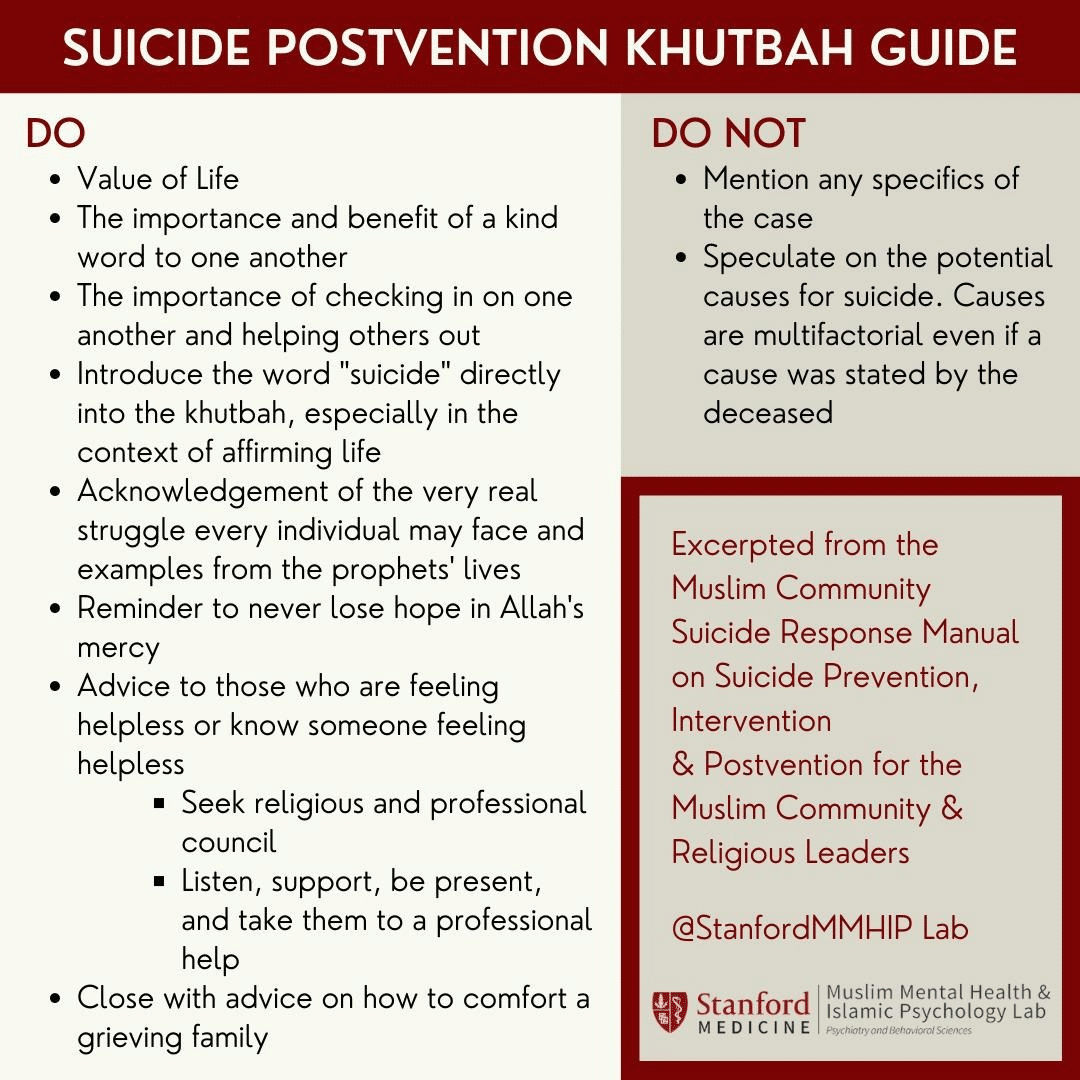

Any death in a community has the potential to deeply affect not only the deceased’s family and close friends, but also the wider community. When someone dies by suicide, the impact on the community and its individual members can be significantly more difficult. While we should strive to create Muslim communities that support and promote mental health as well as approach mental illness in a non-stigmatizing manner, the reality is that suicides can happen despite our best efforts and intentions. In these cases, it is critical that the community responds in an appropriate and prompt manner. Muslim religious leaders (Imams please see our Suicide Postvention Khutbah Guide), mental health professionals, community leaders and advocates, and general community members all have roles that they can and must play in responding to a crisis. Taking the steps outlined here will not only help prevent suicide contagion in the short term, but it will also help the community grieve and heal in the long term.

Suicide is preventable. Mental illness is treatable. And these challenging times are surmountable.Click To TweetIf you are interested in furthering your knowledge on suicide response in the Muslim community, the Stanford Muslim Mental Health & Islamic Psychology Lab has developed a robust, evidence-based and Islamically-grounded suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention manual and training. It provides in-depth, step-by-step guidance for Muslim community and religious leaders that was developed in collaboration with Muslim leaders and suicide experts. The Stanford MMH&IP Lab in collaboration with Maristan.org are also developing an upcoming training and certification program for Muslim across the world to learn how to effectively prevent, intervene, and respond to suicides in their own communities. To learn more or access these materials and trainings, please follow us on social media @stanfordmmhip and join the mailing list at Maristan.org

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of self-harm, please call 911 or one of the following hotlines:

- 24/7 National Suicide Prevention Hotline: 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

- Naseeha Muslim Mental Health Hotline: 1-866-627-3342 (available 9AM – 6PM PST)

- AMALA Muslim Youth Hopeline: 1-855-952-6252 (available 6PM – 10PM PST except Tuesdays and Thursdays)

- Find a Muslim Mental Health Provider in your area here: https://muslimmentalhealth.com/directory/

- Access informational toolkits: https://www.thefyi.org/toolkits/

- To access Muslim Suicide Response Trainings and Manual: Maristan.org

Suicide Postvention Khutbah Guide

Bios:

Rania Awaad M.D., is a Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the Stanford University School of Medicine where she is the Director of the Stanford Muslim Mental Health & Islamic Psychology Lab, Associate Chief of the Division of Public Mental Health and Population Sciences, and Co-Chief of the Diversity and Cultural Mental Health Section in the department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. She is also the Executive Director of Maristan.org. Her research and clinical work are focused on the mental health of Muslims. Her courses at Stanford range from teaching a pioneering course on Islamic Psychology, instructing medical students and residents on implicit bias and integrating culture and religion into medical care to teaching undergraduate and graduate students the psychology of xenophobia. Some of her most recent academic publications include an edited volume on “Islamophobia and Psychiatry” (Springer, 2019), “Applying Islamic Principles to Clinical Mental Health” (Routledge, 2020) and an upcoming clinical textbook on Muslim Mental Health for the American Psychiatric Association. She is currently an instructor at the Cambridge Muslim College, TISA and a Senior Fellow at Yaqeen Institute and ISPU. In addition, she serves as the Director of The Rahmah Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to educating Muslim women and girls. She has previously served as the founding Clinical Director of the Khalil Center-San Francisco as well as a Professor of Islamic Law at Zaytuna College. Prior to studying medicine, she pursued classical Islamic studies in Damascus, Syria and holds certifications (ijāzah) in Qur’an, Islamic Law and other branches of the Islamic Sciences. Follow her @Dr.RaniaAwaad

Taimur Kouser is a researcher at the Stanford Muslim Mental Health & Islamic Psychology Lab and is one of the authors on the lab’s suicide community response manual. He received his bachelor’s degree in Neuroscience and Philosophy from Harvard University. Currently, he is a master’s candidate at Duke University in their Bioethics & Science Policy program and is the recipient of a Fulbright research grant to study at the Center for Neurophilosophy at Ludwig-Maximilian University in Munich, Germany.

Osama El-Gabalawy, MS, leads the suicide line of research at the Stanford Muslim Mental Health & Islamic Psychology Lab, and is one of the authors on the lab’s suicide community response manual. He received his bachelors in Biology, masters in Computer Science, and will be graduating with a doctorate in medicine all from Stanford University. He is an incoming Psychiatry resident at Columbia University.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Rania Awaad M.D., is a Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the Stanford University School of Medicine where she is the Director of the Stanford Muslim Mental Health & Islamic Psychology Lab, Associate Chief of the Division of Public Mental Health and Population Sciences, and Co-Chief of the Diversity and Cultural Mental Health Section in department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. She is also the Executive Director of Maristan.org. Her research and clinical work are focused on the mental health of Muslims. Her courses at Stanford range from teaching a pioneering course on Islamic Psychology, instructing medical students and residents on implicit bias and integrating culture and religion into medical care to teaching undergraduate and graduate students the psychology of xenophobia. Some of her most recent academic publications include an edited volume on “Islamophobia and Psychiatry” (Springer, 2019), “Applying Islamic Principals to Clinical Mental Health” (Routledge, 2020) and an upcoming clinical textbook on Muslim Mental Health for the American Psychiatric Association. She is currently an instructor at the Cambridge Muslim College, TISA and a Senior Fellow at Yaqeen Institute and ISPU. In addition, she serves as the Director of The Rahmah Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to educating Muslim women and girls. She has previously served as the founding Clinical Director of the Khalil Center-San Francisco as well as a Professor of Islamic Law at Zaytuna College. Prior to studying medicine, she pursued classical Islamic studies in Damascus, Syria and holds certifications (ijāzah) in Qur’an, Islamic Law and other branches of the Islamic Sciences. Follow her @DrRaniaAwaad She is also a researcher and the Director of the Stanford Muslims and Mental Health Lab where she mentors and oversees multiple lines of research focused on Muslim mental health.

I’m So Lonely! The Crisis Muslim Parents Are Missing | Night 12 with the Qur’an

When Love Hurts: What You Need to Know About Toxic Relationships | Night 11 with the Qur’an

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Someone | Night 10 with the Qur’an

Fifteen Years in the Shadows: The Strategic Brilliance of the Hijrah to Abyssinia

Ramadan As A Sanctuary For The Lonely Heart

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

[Podcast] Guardians of the Tradition: Muslim Women & Islamic Education | Anse Tamara Gray

Who Am I Really? What Surat Al-‘Asr Teaches Muslim Teens About Identity | Night 1 with the Qur’an

Where Does Your Dollar Go? – How We Can Avoid Another Beydoun Controversy

An Unending Grief: Uyghurs And Ramadan Under Chinese Occupation

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Someone | Night 10 with the Qur’an

When to Walk Away from Toxic Friends | Night 9 with the Qur’an

What Islam Actually Says About NonMuslim Friends | Night 8 with the Qur’an

Week 1 in Review: Is Your Teen Actually Changing? | Night 7 with the Qur’an

Why Your Teen Wants to Change Their Muslim Name | Night 6 with the Qur’an

MuslimMatters NewsLetter in Your Inbox

Sign up below to get started

Trending

-

#Islam2 weeks ago

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

-

#Current Affairs1 month ago

[Podcast] Should Muslims Ally with Conservatives or Progressives? | Imam Dawud Walid

-

#Life1 month ago

[Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy

-

#Islam1 month ago

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

Faraz

April 15, 2021 at 1:46 AM

Jazak Allah Khair!

Pertinent and well laid article… Thanks for the specific guidance on suicide prevention with special focus on Muslims and sharing of useful resources.

May Allah grant you all barakah!

Aisha

June 19, 2021 at 2:40 PM

2 brothers suicide: Tanvir Towhid (21 yo) & Farhan Towhid (19 yo) took their sister & parents, then suicide, in Allen, Texas.

Hundreds of people gathered for funeral prayers at Islamic Association of Allen, to say janazah. Their friends & family all came to mourn them.

Farhan Towhid put on Instagram “Hey everyone, I killed myself & my family.” He studied computer science at University of Texas at Austin. The 2 brothers decided to kill their family, then themselves: “Instead of having to deal with the aftermath of my suicide, I can just do them a favor & take them with me,” the note reads.

Nos

September 10, 2021 at 5:07 PM

Maybe not the wisest of decisions to, after a murder-suicide, blast that suicide news to everyone who would otherwise have not heard it, and show unending love and sympathy for a pair of murderers. Any concern for social contagion? Any evidence this psychiatric treatment works in populations *overall*? If you are an expert, lets look at your results.