#Culture

Day of the Dogs, Part 21: The Eternal Life

Where was his father’s soul right now? What wondrous things was it seeing? What reality had unfolded before his father’s eyes? What terrible truths did he know, but could not share?

Published

See the Story Index for Wael Abdelgawad’s other stories.

This is a multi-chapter novel. Chapters: Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 | Chapter 8 | Chapter 9 | Chapter 10 | Chapter 11 | Chapter 12 | Chapter 13 | Chapter 14 | Chapter 15 | Chapter 16 | Chapter 17 | Chapter 18 | Chapter 19 | Chapter 20

“Go home, Omar. Go home, go home.” – A frog

Peeling Balls

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

They were on Via Argentina, an especially nice street with well maintained apartment buildings, quirky shops and restaurants, and a grassy island in the middle. Parked cars lined the road, and there were zero free spaces. Ivana put on her blinkers and came to a dead stop in the right lane. Immediately horns began to blare as traffic backed up, and angry drivers were forced to merge into the other lane.

Omar got out of the car and walked up a driveway that led into an underground garage belonging to an apartment building. He stopped in front of the little girl who sat dejectedly on the driveway curb, her box of gum packets on the ground between her dirt-encrusted bare feet.

She squinted up at him. “The burned guy.”

“You still peeling balls?” From the way Amelia had used this expression last time, Omar assumed it meant down on your luck and broke.

She made a small yet comprehensive hand gesture that said, “This is my world.” And, “What a stupid question.”

“You want to come with us? Get some food?”

Her eyes narrowed further. “You’re not a vampire?”

“Huh?”

She lowered her voice to a whisper. “They go after street kids.”

“I’m standing in the sun.”

“Oh.”

He beckoned. “Come.” By this time the cacophony of car horns had risen to a crescendo. Drivers rolled down their windows to shout curses at Ivana, reviling her parentage and comparing her to every despised animal they could think of. The girl picked up her box of gum.

In the confines of the car, it was obvious that the child had not bathed. Omar sat in front, while the girl sat in back with Samia, her forehead pressed against the window as she watched the street go by, her box of gum clutched in her lap.

“What’s the plan?” Samia asked in English, so the child would not understand.

Omar sighed. “I want to feed her. After that… I don’t know.”

“No restaurant will let her in,” Ivana replied, still in English. “She have no shoes, and she smell bad.”

“Someplace with outside tables.”

Ivana grinned. “I know a place.” Switching to Spanish, Ivana looked over her shoulder at the girl. “I was a beauty queen.”

Amelia said nothing.

“And I’m descended from Castilian royalty.”

The girl looked impressed. “Your car is pretty.”

Ivana gave a satisfied nod. “Why did you say you don’t have parents?”

Amelia’s Tale

Amelia returned her gaze to the street. Speaking in a monotone, she explained that her mother had been killed in a robbery when she was small, and her father had gone to Colombia to find work, leaving her with her grandmother. That was two years ago, and she had not heard from him since.

Two older cousins, one eighteen and one sixteen, convinced her to travel to Panama with them. They had a distant aunt living here, and thought she could take care of them. They hired on as unpaid swabs on a livestock carrier – a type of ship – carrying live sheep from Brazil to Mexico by way of the Panama Canal. Their job was to clean the animal waste. But the ship was not sufficiently ventilated – “the air got bad,” as Amelia put it – and the eighteen year old died, along with one seaman and several animals.

When they abandoned ship in Colon and found their way to Panama City, the aunt would not take them in. She’d recently gotten married, and her husband said he wouldn’t turn his house into a beggars’ den. The sixteen year old cousin turned to prostitution, and pressured Amelia to do the same. Amelia refused, and they parted ways. She sold gum from morning to sunset, and at night slept in an abandoned building on the Tumba Muerto.

Ivana looked horrified. “Prostitution? You can’t be more than ten years old. Your cousin should be shot!”

The girl shrank from Ivana’s anger. “I’m fourteen,” she said defensively.

Omar was stunned. Fourteen? She didn’t look older than nine or ten. She must be chronically malnourished.

When they stopped at Nadia’s house to pick up Nur, the boy hopped into the back seat. “Who are you?” Nur asked.

“Amelia.”

“Oh.” Nur opened his backpack and took out his Etch-a-Sketch. “Want to draw?”

Amelia smiled for the first time since Omar had met her. “Sure.”

Omar watched with pride. Surely Nur was aware of Amelia’s body odor, and certainly he could see her dirty feet and dusty, disheveled hair. Yet he behaved normally, as if unaware of these things. In that moment, Omar’s heart swelled with love for his son. Tired, he put his head back and closed his eyes.

Someplace To Eat

When the car stopped and Omar opened his eyes to see their destination, he shot a scowl at Ivana. She’d brought them to Panama Viejo Snacks and Lottery. Tio Melo’s shop. Correction – Santiago Francisco Bayano Benjumeda’s shop.

Ivana shrugged. “It’s someplace to eat, primo.”

Uh-huh. They all sat on one of the benches: Omar on one end, then Samia, Nur and Amelia. Omar did not want to enter the shop, but he gave Ivana money and she went inside.

She emerged with a large sack and proceeded to distribute wrapped tuna sandwiches, takeout boxes of chicken chow mein and cabbage dumplings, potato chips, cans of guava and apple juice, and bottles of water. In spite of the Cuban sandwich earlier, Omar realized he was hungry again. He took a chicken chow mein and dug in with wooden chopsticks. Melo’s – argh, Santiago’s – Chinese food was delicious, and after Ivana’s story Omar knew why. The man had spent more than two decades in China.

Ivana squeezed in on the end next to Amelia, and the five of them sat in a row like birds, eating. Amelia wolfed down her tuna sandwich, barely pausing to chew. Omar noticed her sneaking another sandwich out of the bag and hiding it under the bench.

“Slow down,” Samia said. “You’ll make yourself sick. There’s plenty of food. You can have as much as you want.”

Melo emerged from the store and stood in front of them. His face, which had always seemed ageless, was now etched with worry lines. He glanced at Omar, then looked away. “How goes the struggle?”

“I don’t know, Santiago,” Omar replied. “You tell me.”

Omar saw Santiago’s Adam’s apple go up and down. The old man seemed to wither under Omar’s unblinking stare.

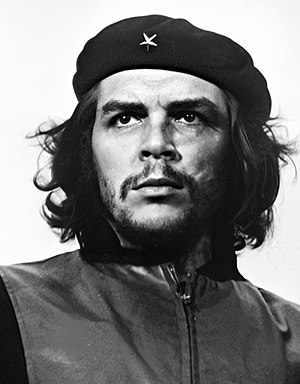

“Che Guevara used to say,” Santiago said, “that the true revolutionary is not guided by hatred, because that is not revolution but vengeance. Nor is he guided by ideology, because that devolves into dictatorship. No, the true revolutionary is guided by love. Maybe…” He paused and wiped his forehead. “Maybe I loved your father so much that I wanted a better world for him. I grew up in the ramshackle, bloody streets of Portobelo, in violence and poverty. Maybe -” his lower lip trembled and his voice broke, and tears began to stream from his eyes. “Maybe I wanted more for Reymundo and all other children like him. And maybe I was utterly, stupidly wrong.”

Ivana set her food on the bench and went to the old man, embracing his slender form. Santiago stood with his arms at his sides, accepting the embrace passively. Ivana held out a hand to Omar. “Come, primo.”

Omar felt such a roiling mixture of emotions that he thought they would combine like chemicals in a bad science experiment and dissolve him. Ivana beckoned again. He looked to the people beside him and saw Nur and Amelia watching him, while Samia sat with her head tilted in that way that indicated she was listening intently.

Who Am I?

Who am I? he thought. And who am I raising my boy to be? He remembered Samia saying, “I feel like there’s an inner sickness consuming you. My instinct tells me the only cure is forgiveness” And he thought of Tio Niko’s words: “I will tell you a secret. Some of the flock… have been with you all along. They never stopped loving you… You know them by what they do.”

What had Santiago Benjumeda actually done? He’d been a friend since Omar was young, caring for him in little ways, bringing gifts to his family, persisting as a giver of kindness.

Even as these thoughts passed through his mind, he realized they were superfluous. He was no longer angry. The resentment and bitterness that had consumed him were gone. They’d been catalyzed by his survival of that crippling weeklong depression, and by his mother’s story, and his uncle’s death, and had been transformed into something else. An understanding, perhaps, that everyone made terrible mistakes, everyone was ashamed, and everyone struggled to return to the light.

He went to the old man, putting an arm around him from the other side. For a moment the strength seemed to leave Santiago’s legs, and he sagged. Omar reacted quickly, circling his arm around Santiago’s back, clutching him. His grandfather returned to himself, and stood straight again. Tears still ran down his cheeks, and he seemed afraid to look at Omar. Omar surprised himself by pulling Santiago’s head toward him and kissing the man on the temple.

No one spoke except for Samia, who whispered to Nur, “What’s happening?” Amelia watched with curious eyes, even as she continued to eat.

A group of teenagers were hanging out in front of the shop. Two girls approached Omar. One smiled shyly. “You’re Omar Bayano, aren’t you?” The two girls giggled.

“Yeah. How do you know me?”

“From the news. You killed that escaped murderer. Can we have your autograph?” The girl produced a school notebook that had been folded in two, and a pen that wrote in five colors simultaneously.

Omar didn’t see any point in correcting the girl’s version of events. Sighing internally, he signed the book.

“How come you’re at this place?” the girl asked.

Omar indicated Santiago. “He’s my grandfather.” Saying these words felt like speaking with peanut butter coating his mouth. It would take getting used to.

“Tio Melo is your grandfather? Oh my God!”

“I’m his cousin,” Ivana said proudly. “I’m also the former Miss Cuba.”

The girls shrieked with delight and gave the notebook and pen to Ivana.

Omar’s phone rang. He answered it and listened as his mother spoke in a strangely calm and controlled tone. After a minute he hung up and looked around at the group.

“The Black Knife is gone. Celio Natá has passed away.”

Don’t Worry, Primo

“You just saw him an hour ago!” Ivana exclaimed.

“He was in bad shape.”

Samia came to his side and slipped her arm through his. “You gave him what he needed to be at peace.”

“What do you mean?”

“You promised to work for his people, and that comforted his heart. And you gave him the testimony of faith, and that comforted his soul. He was able to move on.”

Omar remembered how all the tension had drained out of Tio Celio’s body after reciting the shahadah. It was as if the man had been grasping a lifeline with all his strength, and had decided he didn’t need it anymore.

“The Ngäbe-Buglé elders are meeting tonight. Mamá wants me to come. She wants to arrange an Islamic funeral for Celio, but the elders are refusing. She wants me to show them the video and explain what it means.”

The kids swung their legs and chatted about werewolves and something Amelia called La Ciguapa – a woman with her feet facing backward, who could hypnotize men into following her into the woods, where they disappeared. What was with this kid and monsters? She was going to give his son nightmares.

“I’m not sure what to do about the girl,” Omar said in English.

“Don’t worry, primo,” Ivana said confidently. “I will deal with her. I have a plan.”

Omar shrugged. Weariness was setting in, and he couldn’t think clearly. “Okay.”

Santiago touched his arm. “What about me and you? Are we… alright?”

Omar studied the old man. His grandfather. “Samia’s been wanting to organize a picnic at the beach. We’ll call you.”

When Ivana pulled into their driveway at home, Omar spoke to Amelia. “Do you mind going with this lady? She’s my cousin. She’ll take you wherever you want to go.”

“Is she a vampire?”

“What?” Ivana shot Amelia a disapproving glance. “I’m black. Did you ever hear of a black vampire?”

Amelia screwed up her face, thinking.

Omar shut the car door and waved as Ivana drove off, going too fast as usual.

He’d done a lot for his first day out of bed. It was all he could do to perform wudu’, pray Asr and fall into bed, setting his alarm for just after sunset so he could pray Maghreb and attend the meeting, which was being held at his mother’s house.

The Meeting

The meeting was already underway, and it was bedlam. A 30ish woman in a purple nagua dress, sneakers and a straw hat pounded the table. “Don Celio was a good Christian servant! It would be an insult to bury him with some heathen tradition.”

Ximena leaped to her feat. “Are you calling me a heathen? I believe more than you, because I worship only God! As for Don Celio, he never set foot in a church. He used to say that he and God had a mutual pact to leave each other alone. He never professed any faith until he converted to Islam.”

“Which I still doubt,” the woman in the hat said. “It sounds like a fairy tale.”

“It’s not,” Omar said, and they paused, looking at him. There were eight people there: Omar’s mother; the Krägä Bianga; Governor Amauro; a man with a once-broken nose and naturally spiky hair that stood up like cactus spines, who Omar recognized as one of Don Celio’s sons; two other men Omar did not know at all; and the angry woman in the hat. There was no sign of his mother’s husband Masood.

Ximena introduced everyone to him, starting with the spiky haired man, who, she said, was Ismael, the new king of the Ngäbe-Buglé people.

“What about Nicho?” Omar asked.

The angry woman waved a hand. “He’s a drunk.”

“Finalizing Ismael’s appointment,” Ximena said, “was one of the things we met to do.”

“We?”

“I have been elected to the Council of Elders.”

“Against my wishes,” the angry woman said sourly. “You are not Mama Tada. You are not even Christian.”

“Then get out of my house and go,” Ximena said hotly. “And forget about receiving any further funds from me.”

Amauro made a soothing gesture. “Easy, Ximena. You are one of us, it’s done.”

This was a side of his mother Omar had never seen. He remembered her slapping Nicho when the man grabbed his shirt. She’d always been submissive, or so it seemed to him. But she had changed. It was as if, in confessing her appalling weakness to Omar, she had dispensed with it, emerging transformed from the chrysalis of truth. She was done being trampled. This realization moved Omar, and he felt a strange thing stirring in his breast: pride for his mother.

The other two men, Omar learned, were governors of the other two Ngäbe districts, while the woman was Zuli, high priestess of the Mama Tada – the native Christian cult of the Ngäbes. Mama Tada, Omar knew, was founded in 1961 when a Ngäbe woman named Besiko saw Jesus and Mary ride up to her on a motorcycle. The religion emphasized disengagement from outsiders, and abolition of alcohol, wife beating, and fences between properties. Half the Ngäbe people followed Mama Tada. They even had their own police force. This priestess Zuli probably commanded more influence than Ismael would as king.

“Show them the video,” Ximena urged.

Omar played it. When it was done, Zuli scoffed. “He was drugged. He didn’t know what he was saying.”

“Play it again,” Ismael – the new king – said. Omar played it.

“Explain it,” Ismael requested.

Omar explained the basics of Islam, emphasizing the fact that Muslims believed in Jesus and Mary, but as a Prophet and a holy woman, not as divine beings.

“What is it you wish?” Ismael wanted to know.

“He must be given an Islamic funeral,” Ximena broke in, “and buried in an Islamic cemetery.”

Kissed by the Wind

The room broke out in an uproar. Zuli’s face turned pomegranate red as she shouted that Don Celio could never be buried outside the comarca. Ximena hollered back that Celio’s faith must be respected. Ismael looked thoughtful. In spite of his odd, vaguely punkish appearance, Omar thought he might make a good king.

“I have a proposal,” Omar said. The argument continued, so he repeated himself more loudly. Finally eyes turned to him. “Give him a Christian service, and bury him on the comarca, but not in a Christian graveyard. Bury him in a wild place, on the side of a mountain perhaps, caressed by the wind.”

Virtually at the same time, Zuli snapped, “Unacceptable,” while Ximena said, “How is that a compromise?”

Irritated, Omar said, “Excuse us,” and took his mother into the bedroom. “Mamá, you’re on the council now, and I’ve committed to working with them. We need their good will. The Prophet, sal-Allahu alayhi wa-sallam, said that the Muslim who dies in a fire is a shaheed. Celio died from the effects of a fire. His soul is in Jannah. What does it matter if they give him a Christian service? It’s only his body. We can pray for him ourselves as well.”

His mother patted his cheek. “You were always wiser than me.” When they returned to the living room, she announced her agreement with Omar’s proposal.

“In that case,” Ismael, said, “It will be done. I think my father would like being on the side of a mountain, kissed by the wind.” He smiled at Omar.

Zuli grumbled, but the decision had been made. Omar only hoped that the priestess would not prove to be an enemy in the future.

AIR

Three days later, Omar sat on the back of a powerful brown stallion, making his way up a trail on the ridge of a mountain spur. His horse was tethered to the one in front of him, which was ridden by an experienced Ngäbe horseman, so all Omar had to do was sit still and enjoy the ride. The mountain fell away on the sides, its steep slopes covered in oak trees, magnolias, umbrella-shaped ceibas, massive guanacastes, and bamboo and ferns in the understory. The sun was harsh and unbroken. Birds chattered and sang. Now and then an opossum, armadillo or ñeque waddled or bounded out of the way, or a sloth rustled in the leaves of a tree.

Samia was in the city, working on Indigenous and Refugee Advancement, the name they’d given to the new organization they’d set up. In Spanish it was Adelanto de Indígenas y Refugiados, or AIR for short. Breathing this pristine mountain air, Omar found the name appropriate. AIR would help people breathe, metaphorically speaking.

Puro Panameño had given them a grant to get started. They’d already rented an office in Bella Vista, and Samia had signed on as general manager. Naris Muhammad would consult in the effort to stop the government’s construction of the Pared Blanca dam on Ngäbe land. Omar felt that might be too big of a bite for AIR to chew. But the Ngäbe governors insisted it was a top priority. Aside from that, AIR was setting up a classroom to teach literacy and computer skills to Venezuelan refugees and Ngäbe laborers, as well as a food donation program. These were the kinds of things Omar felt they should be doing to start. Time would tell.

As Omar climbed higher, banks of mist billowed down from the mountain peaks, coating his skin. Behind him, the Pacific Ocean was hazy and blue far below. They passed tiny, impoverished Ngäbe hamlets. Stray dogs appeared half starved. Higher up, they passed coffee, cocoa and corn farms, some planted in thin, stony soil, where the yields were undoubtedly poor. The Ngäbes were not mountain people originally. They had once lived on the coasts, but upon the arrival of the Spaniards had fled to the highlands to escape genocide.

Pandemonium

Celio Natá was buried not on a mountainside, but in a large meadow surrounded by forest. A simple headstone had been engraved with a cross. The meadow was packed with men and women. There was not a single white or Latino face in sight.

Priestess Zuli gave a short sermon in Ngäbere, of which Omar understood something about eternal salvation in the blood of Christ. Ismael followed with a few words of praise, and the service was complete. There was no coffin nor even a shroud. Celio’s body, adorned in the standard Sunday outfit of slacks and buttoned shirt, was lowered into the grave. People shoveled dirt in by hand, and Omar pushed his way forward so he could participate. The soil was rich and black.

Immediately, people began to drink. Even teenagers could be seen guzzling hard alcohol. When Ismael wandered over to him and shook his hand, Omar expressed his surprise. “I thought Mama Tada banned alcohol?”

“Not all of these people are Mama Tada. Anyway, even the priestesses overlook the drinking on days like this.”

People gathered into knots where they sang and danced. Fights broke out among the young men, and no one seemed to care. Some wept openly, completely unlike the normally stolid bearings of these people. It was pandemonium, and it made Omar very uncomfortable. He retreated to a quiet spot where he sat under a tree and waited for the whole thing to burn itself out.

These might be his people by blood, but the cultural differences were vast. He didn’t know if he would ever fully understand them. The truth was that his people were the Muslims. That was the way of life he grasped and loved, and Muslims were the people he understood, even the ones who were closed-minded, racist, or provincial. But this was the direction he’d chosen and the deal he’d made, and he had to trust that Allah would guide him on this path.

The Eternal Life

Rather than go directly home, he exited the highway into Arraijan, and made his way to the Islamic cemetery. It was after dark, and the cemetery was unstaffed at this time, but the gate was secured with a simple combination padlock, and Omar knew the code. He entered it, drove in and parked in the small lot.

The cemetery grounds were bordered by lush trees encircled with flower beds. Thick grass grew over the graves. The individual graves had plaques set flush into the ground. The cemetery was not brightly lit, but Omar knew the location of his father’s grave as well as he knew the layout of his own home. He sat on the grass beside the grave, and made dua for his papá, that Allah would widen his grave, fill it with light, forgive his sins and make him one of the people of Jannah.

The night frogs and crickets were as loud as an orchestra. The occasional bird called, and fruit bats flicked past overhead, emitting tiny squeaks.

“It’s been a strange time, Papá,” he said out loud. “Sometimes I wish so much that you were here. I want it more than food or air.” But his father would never be here, on this earth. It was the other way around: one day it would be Omar joining his dad.

His eyes traveled to the clear grass bordering this grave. His mother had purchased this entire row. One day she would be buried next to Papá, and Omar and Samia beyond, and perhaps their children beyond that. It was a sobering thought. Everything came down to this. He thought of an ayah from Surat Al-Ankaboot: “And this worldly life is nothing but diversion and amusement. And indeed, the home of the Hereafter – that is the [eternal] life, if only they knew.”

Where was his father’s soul right now? What wondrous things was it seeing? What reality had unfolded before his father’s eyes? What terrible truths did he know, but could not share?

A cicada let out a loud buzzing call, and a bird answered. The frogs had grown even louder, and one seemed to have found a drainage pipe, amplifying its voice. “Go home, Omar,” it seemed to be saying. “Go home, go home.” Nur might already be in bed, but Samia would be waiting up. Samia, his heart outside his own body. His partner in love, grief, life or death.

He kissed his own palm then rubbed it on the grass over his father’s grave. “I love you, Papá. I will watch over your father Santiago, and your grandson.”

He remembered his offer to Santiago to join them in a picnic. A picnic sounded wonderful right now. They would have to do that soon.

The night air had awakened him. He rose to his feet, and headed home to his family.

Next: Day of the Dogs, Chapter 22 – The Conch (the final chapter!)

Reader comments and constructive criticism are important to me, so please comment!

See the Story Index for Wael Abdelgawad’s other stories on this website.

Wael Abdelgawad’s novels – including Pieces of a Dream, The Repeaters and Zaid Karim Private Investigator – are available in ebook and print form on his author page at Amazon.com.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Wael Abdelgawad's novels can be purchased at his author page at Amazon.com: Wael is an Egyptian-American living in California. He is the founder of several Islamic websites, including, Zawaj.com, IslamicAnswers.com and IslamicSunrays.com. He teaches martial arts, and loves Islamic books, science fiction, and ice cream. Learn more about him at WaelAbdelgawad.com. For a guide to all of Wael's online stories in chronological order, check out this handy Story Index.

When It’s Hard to Forgive: What Parents Need to Know About Islamic Forgiveness | Night 13 with the Qur’an

I’m So Lonely! The Crisis Muslim Parents Are Missing | Night 12 with the Qur’an

When Love Hurts: What You Need to Know About Toxic Relationships | Night 11 with the Qur’an

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Someone | Night 10 with the Qur’an

Fifteen Years in the Shadows: The Strategic Brilliance of the Hijrah to Abyssinia

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

[Podcast] Guardians of the Tradition: Muslim Women & Islamic Education | Anse Tamara Gray

Who Am I Really? What Surat Al-‘Asr Teaches Muslim Teens About Identity | Night 1 with the Qur’an

Where Does Your Dollar Go? – How We Can Avoid Another Beydoun Controversy

An Unending Grief: Uyghurs And Ramadan Under Chinese Occupation

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Someone | Night 10 with the Qur’an

When to Walk Away from Toxic Friends | Night 9 with the Qur’an

What Islam Actually Says About NonMuslim Friends | Night 8 with the Qur’an

Week 1 in Review: Is Your Teen Actually Changing? | Night 7 with the Qur’an

Why Your Teen Wants to Change Their Muslim Name | Night 6 with the Qur’an

Trending

-

#Islam2 weeks ago

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

-

#Life1 month ago

[Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy

-

#Islam1 month ago

How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

-

#Islam4 weeks ago

[Podcast] Guardians of the Tradition: Muslim Women & Islamic Education | Anse Tamara Gray

Umm ismael

April 8, 2021 at 10:27 PM

Asslam u alaikum

You do know brother that giving an unislamic burial to a Muslim isn’t right not matter what the situation. It’s injustice against him and one of his rights upon his fellow Muslims. You write so well and inspire many. Do rewrite this so it doesn’t become inspirational for someone else in the same situation. That is my advise as your Muslim sister.

Wael Abdelgawad

April 9, 2021 at 12:43 AM

Wa alaykum as-salam. If my stories inspire people, alhamdulillah. But I also have to write a realistic story. Omar does not have custody over Celio’s body, and does not have the right to determine what sort of funeral he will have. Also, it doesn’t mean that the Muslims will not also pray for him. I’ll address all of this in the next chapter inshaAllah.

M

April 9, 2021 at 1:28 AM

This is amazing. May Allah purify your deeds and bless you and your loved ones. Thanks.

Wael Abdelgawad

April 9, 2021 at 5:07 PM

Thanks M, I appreciate it. Ameen, and you as well.

Mohamed

April 12, 2021 at 11:51 AM

As salaamun aleikum brother Wael,

First of all, ramadan mubarak to both you and your family, and May He Ar-Rahmaanu Ar-Raheem bestow His mercy, forgiveness, barakah & blessings and prosperity both in our deeds and our eemaan for all of the muslims around the world in this blessed month of ramadan…Allah-humma Ameen

Just wanted to confirm if you’re still posting the last chapter (because I think you said that it would be published 3 days later meaning sunday 11th of April)…so is there any new updates in regards to the last chapter and when it will be posted in shaa Allah…?

Wael Abdelgawad

April 12, 2021 at 12:17 PM

Mohamed, wa alaykum as-salam, and Ramadan mubarak to you and your family as well. And ameen to your dua.

Yes, I did say that about 3 days. But… I’ve been participating in a short story contest called NYC Midnight, and they sent me the story challenge on Thursday night. I didn’t realize it was coming so soon. I had three days to finish the story, and I was working feverishly until the deadline which was last night (I finished with 35 minutes to spare). So I didn’t have a chance to work on the last chapter of Day of the Dogs at all. I will work on it now and hopefully post it on Wednesday, if MM has no objection. They usually don’t like to publish fiction during Ramadan, but maybe they’ll make an exception since this is the last chapter.

Wael Abdelgawad

April 16, 2021 at 7:48 PM

Note to readers: I was stuck on the last chapter for a while. There was something I needed but I wasn’t sure what it was. It’s moving along again, and I’m almost done. Just a little longer, inshaAllah.