#Life

RBI: Reviving Baseball In The Islamic Community

Published

A couple of months ago, I spent a few days in Arizona during Major League Baseball’s annual spring training.

If you’ve never been, spring training is like a month-long live music festival, with baseball replacing bass as the soundtrack. Half of the league’s teams convene in Arizona, the other half gather in Florida, and fans from all over the world descend upon these balmy locales to watch their favorite teams and players prepare for the upcoming season in a series of exhibition games.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

I made the trip to Arizona this year to see my favorite baseball team (the Seattle Mariners) and my favorite player (Milwaukee Brewers pitcher Dontrelle Willis, who actually announced his retirement during spring training) in what is becoming something of an annual get-together for some of my family.

Before my wife and I landed at Phoenix International Airport, however, I wasn’t sure what to expect as a Muslim in Arizona. I had my preconceived notions, considering that we were entering a politically “red” state that has a history of controversial anti-immigration legislation and once rescinded Martin Luther King Day. But a quick online search turned up a couple of masjids near our resort, as well as a link to the Arizona Muslim Voice, a community newspaper based in Phoenix. I also found an article from 2011 in which the Arizona Muslim Voice editor speculated that Phoenix’s Muslim population had grown by more than 100,000 in the previous decade.

So while it wasn’t quite Philadelphia or Dearborn, Mich., Phoenix did not appear to be a ghost town for Muslims, either. That was good enough for me.

And over the course of five days at spring training, I saw Muslim sisters admirably wearing headscarves and long black garments in the 80-degree desert heat. I saw Muslim brothers rocking kufis and tell-tale beards with whom I could exchange knowing nods of the head. I met one brother working at the airport whose face lit up at the sight of a fellow Muslim entering his city as a tourist. I saw quite a few Muslim baseball fans.

What I did not see were Muslim baseball players.

For a sport that embraces the label of “America’s pastime,” baseball — especially at its highest level — has not always represented the demographic diversity of the United States. While Major League Baseball earned an “A” grade in its racial hiring practices on the 2014 Racial and Gender Report Card, it had a less admirable “C+” in gender hiring practices. Almost 40 percent of major-league players are racial minorities, thanks to the sport’s strong grip in Latin American and Asian countries, but the number of Black players has been dropping for years and continued to drop in 2014. Only 8.2 percent of the league’s players are Black.

Diversity in baseball, like everything in baseball, comes with a backstory.

Jackie Robinson’s MLB debut in 1947 is canonized as the moment that paved the way for current Black stars like Andrew McCutchen, Jason Heyward and C.C. Sabathia, and MLB has made a point to retroactively adopt the old Negro Leagues into its own historical narrative. (Even though it was MLB’s own racism and discrimination against Blacks that made the Negro Leagues necessary.) In response to the recent downward trend of Black players, MLB invested in a program called Reviving Baseball In Inner Cities (RBI) designed to foster interest in baseball among young athletes whose urban communities often lacked quality playing surfaces and organized youth leagues.

Latino players were allowed to play in the majors before Black players were allowed, and today there is not one MLB organization that does not have at least a handful of Latino stars on its main roster and/or in its developmental system.

The 1990s and early-2000s witnessed the beginning of an influx of MLB players from Asia, headlined by South Koreans like Chan Ho Park and Japanese standouts like Ichiro Suzuki.

And Jewish players have history in pro baseball going back some 150 years, with Hall of Fame talents like Hank Greenberg and Sandy Koufax preceding modern stars like Ryan Braun and Ian Kinsler.

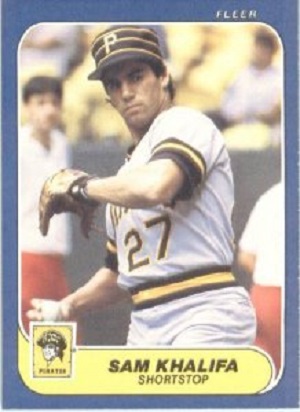

But to the best of anyone’s knowledge, there has been one — and only one — Muslim player in major league history: Sam Khalifa.

The No. 7 overall pick in the 1982 MLB draft, Khalifa played shortstop and second base for the Pittsburgh Pirates for parts of three seasons in the 1980s. Three years after he’d been named Arizona state high school player of the year at Sahuaro H.S. in Tucson, Khalifa made his major-league debut as a 21-year-old. At the time, he was the seventh-youngest player in the majors.

Khalifa was mostly a backup with the Pirates, never appearing in more than 95 games (out of a 162-game schedule) in any of his three MLB seasons. Khalifa had a .219 career batting average, hitting 20 doubles, three triples and two home runs with 37 runs batted in and a .964 fielding percentage.

Khalifa spent most of 1987 and all of 1988-89 in the minor leagues. In the 1990 offseason, still only 26 years old and receiving interest from the San Diego Padres, Khalifa retired from baseball following the assassination of his father, Rashad Khalifa, an Islamic scholar.

Sam Khalifa may have played the same position Jackie Robinson played on the diamond, but he was no Jackie Robinson. And I’m not talking about talent, but historical significance. After Khalifa, there was no flood of Muslim players entering Major League Baseball. There wasn’t even a trickle.

He remains the first and, as far as anyone I’ve talked to can tell, the only Muslim to play in the majors.

There have been no Muslim MLB managers, either. And current Los Angeles Dodgers general manager Farhan Zaidi isn’t just the first and only Muslim GM in MLB history, he’s the first and only Muslim GM in any American major sports league. Chicago Cubs assistant GM Shiraz Rehman is another Muslim in a prominent front-office position.

Why aren’t there more Muslims involved at the highest levels of baseball?

First things first, I don’t think this is at all like the “old days” of MLB, when White management deliberately collaborated to keep Black people entirely out of the game; and even well after Jackie Robinson, maintained unofficial limits on how many Blacks could be on one roster.

There is no ugly history of anti-Muslim attitudes in baseball — certainly nothing close to the vitriol hurled at Blacks and other minorities. Sam Khalifa wasn’t run out of the game. In a 1986 article in Aramco World magazine, he talked about how he was being treated.

“Sure, there’s always some clubhouse ribbing and I’ve been called ‘the shaikh,’ but it’s been in fun,” Khalifa said. “I never felt any prejudice in Arizona or anywhere else. People respect me for what I am and that’s good.”

I don’t think Muslims are being kept out of Major League Baseball today.

I don’t think many Muslims want in.

For one reason or another, baseball has not caught on in the Muslim American community.

Are there socioeconomic issues creating a divide between a sometimes expensive sport and a community that includes many immigrants who live at or below the poverty line?

Is it a matter of scheduling, with baseball suffering due to occupying the same part of the calendar as soccer?

Is there bound to be an awkward fit between the American pastime and a community whose roots are not in America, a community that is often made to feel rejected and unwelcome by many Americans?

Or is there something inherently, religiously un-Islamic about baseball?

Rany Jazayerli is one of today’s most influential Muslim figures in baseball. The full-time dermatologist is a part-time writer for ESPN who co-founded Baseball Prospectus and for years maintained Rany on the Royals, a blog dedicated to his favorite team, the Kansas City Royals.

I asked Jazayerli why baseball is not as popular with Muslim-Americans. Here is his theory:

Baseball, rather than football or basketball, is the sport most identified with traditional American culture, and I’m using “traditional” as a euphemism for “white.” This isn’t because of anything that Major League Baseball is doing per se — there is a long and storied history of African-Americans playing baseball, and while African-American participation has dropped in recent decades, their place has largely been taken by Latin American players. The sport on the field is not dominated by whites — but the fan base for MLB is mainly white, certainly far more so than the fan bases for the NFL and the NBA.

The NFL is so big that it simply dominates all walks of American culture, while the NBA, which is a league populated mostly by African-Americans, has been associated with American “counterculture” — which here I’m defining as simply the culture of minority groups — for decades. The rise in the NBA’s popularity over the years may be connected to the increasing popularity of countercultural entertainment in general.

And here’s the key point: American-born Muslims as a whole have, I believe, embraced American counterculture more than traditional American culture. I’m not saying this is right or wrong; I think it’s actually quite inevitable overall, because most immigrant Muslims to this country are not white, and white America continues to regard non-white immigrants with considerable suspicion. If you are the child of Pakistani parents who didn’t feel comfortable with your parents’ culture growing up in New Jersey, and you didn’t feel comfortable around the white majority in school who made you feel like an outsider growing up, who may have taunted you with racist taunts, then you’re going to start identifying with other ethnic minorities in America. You’re going to listen to hip-hop music, and you’re going to watch basketball. You’re unlikely to watch baseball, and you’re even less likely to watch hockey, and you’re *really* unlikely to listen to country music, which is not only dominated by whites but has legitimate issues with how welcoming it is of minorities in America.

It’s probably not a coincidence, then, that my family is from Syria and I pass as “white” by any reasonable definition of the term. I didn’t look like an outsider to white America growing up, and I never felt like an outsider, and I fell in love with baseball from an early age.

I don’t want to overstate the correlation — there are plenty of brown Muslim Americans who are big baseball fans, and several who work within the game — Adnan Virk hosts ESPN’s Baseball Tonight, and Farhan Zaidi is the GM of the Los Angeles Dodgers. (Disclaimer: both are actually Canadian.) But I also don’t want to ignore something which is pretty obvious: whereas 80 years ago, immigrants to America were usually European, and so could integrate into American society pretty seamlessly if they learned the mainstream culture — which meant baseball — today immigrants to American are not typically white, and so unless they come from cultures which have already embraced baseball, they are likely to gravitate to American sports which are the province of minorities, like basketball.

So in order for baseball to grow in popularity among Muslim Americans in the future, one of two things — preferably both — needs to happen. Major League Baseball can find a way to make inroads among minority communities, which they can start to do by de-emphasizing history and tradition when it comes to marketing the game. MLB is legitimately interested in connecting with the African-American fans that it has lost over the years, and the concerns raised by Chris Rock in this takedown of MLB will get attention from the Commissioner’s Office.

But the other thing that needs to happen is that Muslims in America need to better identify with being American, to accept that they can be fully American without compromising their faith one bit, and to make an active effort to not only integrate with mainstream American society but to be actively engaged with bettering American society, rather than cocooning themselves into their own insular societies. Note that this should be the actual goal regardless of what it has to do with baseball; I think seeing more Muslims become baseball fans would be a product of more active engagement with American society, not the other way around. In the grand scheme of things, it’s not important whether more Muslims become baseball fans. But more Muslims becoming baseball fans is a likely by-product of more Muslims recognizing themselves as fully American, and not sensing any conflict between the two.

The problems facing baseball that Jazayerli and Rock bring up can possibly be fixed by concerted, long-term marketing and community outreach efforts. And even if they work, the results may not be plainly visible for a few years.

Or, baseball could get lucky like some other sports and have that one superstar emerge who Pied-Pipers a legion of young fans to follow in his footsteps.

The NBA became a hit in China on the back of Yao Ming. Boxing’s modern-day popularity among Filipino fans is tied mostly to the rise of Manny Pacquiao. Tiger Woods is viewed as golf’s liaison to Black America, while Danica Patrick has been credited with drawing more female interest in NASCAR.

If one Muslim baseball phenom gets to the major leagues and blows up, that could do more to endear the Muslim community to the sport than however-many millions MLB might be willing to throw into a marketing campaign.

But it’s kind of a chicken-vs.-egg thing, because baseball may not find that Muslim superstar without first doing its share of work to promote the game to Muslims — or less specifically, to counterculture America and young America.

“The first Muslim star is not going to be from a Muslim country,” ESPN’s Adnan Virk, a Muslim of Pakistani descent who grew up in Canada, was quoted in a 2013 article for Fan Graphs. “It’s going to be a guy like me.”

The first Muslim Major League Baseball star will also have to be ready for all that comes with being the Jackie Robinson of Muslim baseball. Although it’s been 30 years since Sam Khalifa played, the next Muslim MLB player will be navigating a whole new world and a whole new America with different attitudes regarding Muslims.

He will have to find his way in the quintessential American sport in an America that has turned his people into a dangerously marginalized minority.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we're at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small. Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you're supporting without thinking about it.

Amaar Abdul-Nasir was born and raised in Seattle, Wash., and received his B.A. in Journalism from Seattle University. A sports writer and editor by trade, Amaar founded UmmahSports.net, which focuses on Muslim athletes and health and fitness in the Muslim community, following his conversion to Islam in 2013.

[Podcast] Palestine in Our Hearts: Eid al-Fitr 1445 AH

Foreign Affairs Official Resigns Over Gaza Genocide

A Ramadan Quran Journal: A MuslimMatters Series – [Juz 30] Solace For The Sincere And Vulnerable

IOK Ramadan: The Importance of Spiritual Purification | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep30]

IOK Ramadan: The Power of Prayer | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep29]

IOK Ramadan: 7 Qualities of Highly Effective Believers | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep18]

IOK Ramadan: Choose Wisely | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep15]

IOK Ramadan: Shake the Trunk of the Tree | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep16]

IOK Ramadan: They Were Not Created Without Purpose | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep23]

IOK Ramadan: Appreciating the Prophet ﷺ | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep22]

IOK Ramadan: The Importance of Spiritual Purification | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep30]

IOK Ramadan: The Power of Prayer | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep29]

IOK Ramadan: The Weight of the Qur’an | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep28]

IOK Ramadan: Families of Faith | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep27]

IOK Ramadan: Humility in Front of the Messenger | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep26]

Trending

-

#Islam2 weeks ago

IOK Ramadan: 7 Qualities of Highly Effective Believers | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep18]

-

#Islam2 weeks ago

IOK Ramadan: Choose Wisely | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep15]

-

#Islam2 weeks ago

IOK Ramadan: Shake the Trunk of the Tree | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep16]

-

#Islam2 weeks ago

IOK Ramadan: They Were Not Created Without Purpose | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep23]

MY

May 30, 2015 at 9:16 AM

Cricket.

Most Pakistanis and Indian descent population play and administer cricket in US. You will find some fine administrators managing cricket leagues and playing as full time players at the same time. Baseball is just not the game that can replace Cricket for them.

This probably takes a big demographic of “to-be” Baseball administrators/players though many of us follow Baseball just as fellow Americans do.

June

May 30, 2015 at 12:47 PM

Assalamu Alaykum,

This was fascinating to me as an American revert who has always been a fan of baseball. There are some interesting points made about counterculture, integration, and maintaining faith. I had been thinking about if there were/are/will be any Muslim baseball players. I tell my husband I’ll raise our kids to love baseball (and I do secretly hope one of them wants to become a pro) So I may only be a matter of time.

On a side note: “If one Muslim baseball phenom gets to the major leagues and blows up…” I was amused by this. I know what you mean and yet… you know… (Unintentional, I’m sure, but amusing nonetheless.)

Hamza 21

June 4, 2015 at 6:30 PM

“Khalifa retired from baseball following the assassination of his father, Rashad Khalifa, an Islamic scholar.”

Rashad Khalifa had a degree in biochemistry not Islamic studies nor Shari’ah. He also, more importantly, proclaimed the Qur’aan was wrong when confronted with evidence his mathematical code of the Qur’an was erroneous.

Pingback: Muslim players to watch this NFL season | Ummah Sports

Pingback: » Muslim Players to Watch This NFL Season

Mark

August 3, 2016 at 12:52 AM

Thank you for your research and interesting writing. I am not Muslim, but am a huge baseball fan.your article answered my curiosity about Muslims in baseball. It is interesting the way baseball reflects sociology of the United States. I hope the game becomes fully integrated. America’s national pastime should reflect American demographics.

Syed

February 2, 2020 at 10:36 AM

Rashad Khalifa claimed to be the messenger of Allah. He was a dajjal. He was not an islamic scholar by any means. He was not even a muslim. He says himself,

“During my Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, and before sunrise on Tuesday, Zul-Hijjah 3, 1391, December 21, 1971, I, Rashad Khalifa, the soul, the real person, not the body, was taken to some place in the universe where I was introduced to all the prophets as God’s Messenger of the Covenant.” (The Quran, the Final Testament by Rashad Khalifa).